I was so excited after a day of wandering the aisles of Art Basel Miami Beach last December, that I virtually salsa-stepped my way into South Beach! What was seen and said, and what was not seen and said had kept me engaged for hours. I saw artists from many places (the Philippines, Italy, Africa and China to name a few) using diverse media to present art commenting on both the United States (US) and global society, as well as politics. These were not at all works from the ‘Other’ – peripheral societies and artists that might hesitantly venture a comment to a traditional, powerful, parent.

These artists participated fully in the current conversations on race, politics and history.

These artists in their works issued full-throated, clear, clarion calls to action or warnings.

They spoke as a vested interest.

They created as equals.

This was art as a sort of diplomatic network. To me, this was a profound and positive impact of globalization which was worth shouting about.

But, I am getting a little bit ahead of myself.

Why, as readers interested in Southeast Asian art should we be concerned with art events in the US? Well, Art Basel Miami Beach is only the exhibition that is most attended worldwide by collectors (according to UBS and reported in Art News), and much was on show and offer. In our globalised world, it is indeed important to have a sense of how Southeast Asian art fits in with and is represented at key international art events.

Art Basel Miami Beach featured works by approximately 4000 artists from over 250 galleries. At times I chuckled to see how many works by one artist were on show. I counted no less than 6 versions of Jeff Koons’ Gazing Ball series of works. Here’s a selection below:

At times, I lost my breath, as when I caught sight of Robert Rauschenberg’s Periwinkle Shaft (1979-1980):

There was truly something for every taste and interest.

Art Basel Miami Beach divided into different sectors and the diversity inside the convention centre was matched by a diversity of events outside including film, satellite shows and exhibitions as well as a ‘Conversations’ series with artists, critics and others. Here’s where the Southeast Asian (and indeed, Asian) connection was keenly felt. Asian galleries and artists were well-represented including amongst them: Taro Nasu from Tokyo, Gallery Antenna Space from Shanghai, Tyler Rollins from New York, the Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI) Rikrit Tiravanija, and Ai Wei Wei.

I found it easy to follow the disappearance of the ‘Other’, as I viewed the many works from artists all over the world, offering political and social commentary – especially regarding the US. The best of these displays used clear imagery, humour and hope, and avoided what John McDonald identifies as “works that are morally admirable and artistically deplorable.”

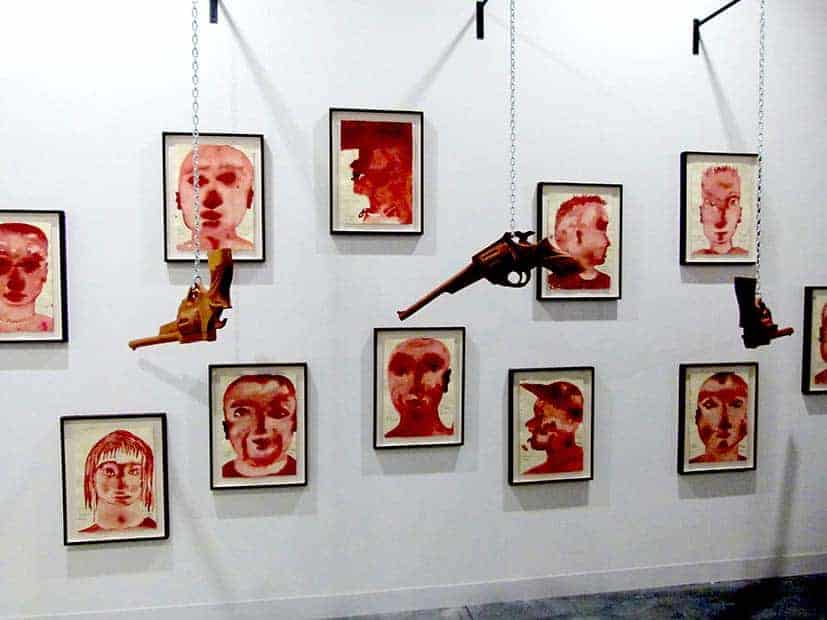

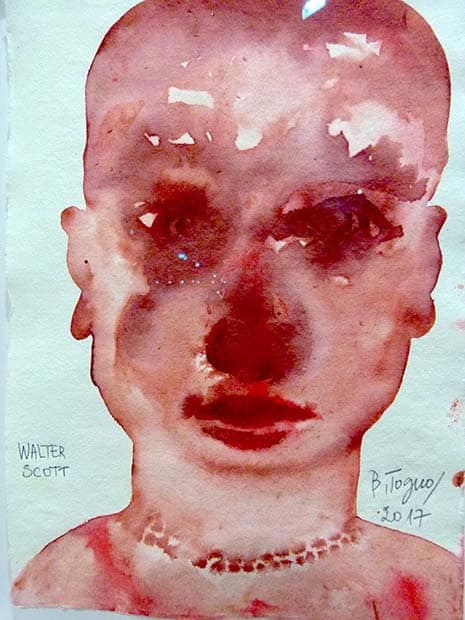

As conversation in the US in the fall of 2017 kept the focus on racial issues and Donald Trump, the fact that many works echoed this theme was not a surprise. Barthelemy Toguo’s Black Lives Matter (2017) – created a haunting, almost abstract image of the victims of police killings. This work is clear in not letting go or refining the history of the killings. This particular artist was born in Cameroon:

No matter their place of origin, artists at Art Basel Miami challenged society not to turn away by presenting works on the theme of immigration and migrants.

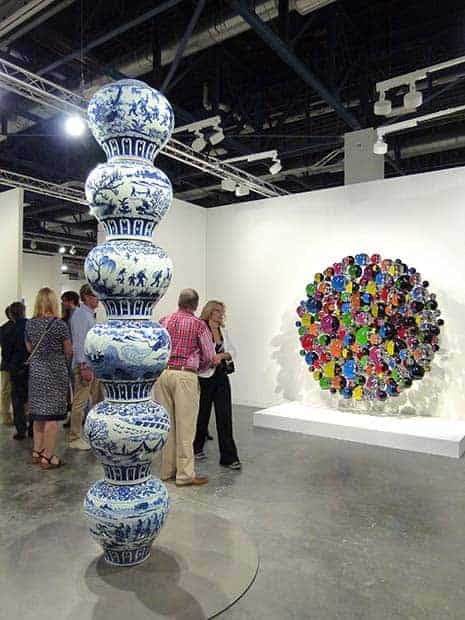

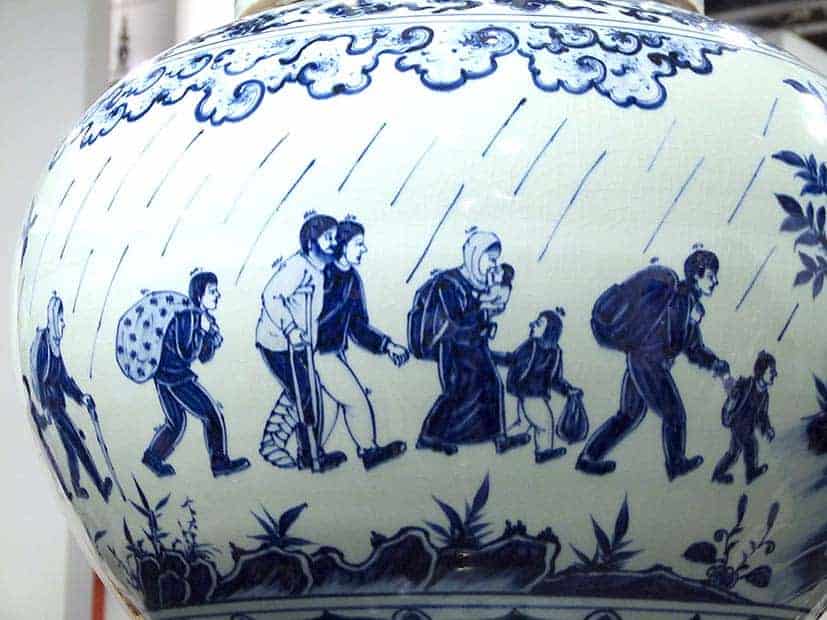

My first choice on this theme was Stacked Porcelain Vases as a Pillar (2017) by Ai Wei Wei:

Ai, in an interview with Time Magazine, noted that,

“before the Berlin wall collapsed, about 11 nations had border [walls] and fences….Now it’s jumped to 70.”

In addressing the concerns by some about being overrun by migrants, Ai commented that such views were,

“against the ideology that we’re all created equal … and it’s just such a backward movement.”

His pillar of pots took me on a trip through time, cause and effect. As I looked at each of the six vases, I noticed a narrative of tragedy. Starting at the top of the pillar – the decoration on the vase depicted war and fighting:

Moving down the pillar, I saw the destruction of property, and images of people forced to migrate and leave the known behind:

The message of the displacement caused by conflict was unmissable. The call to action was clear in this stack of vases created in colours and shapes reminiscent of more classical Chinese porcelains.

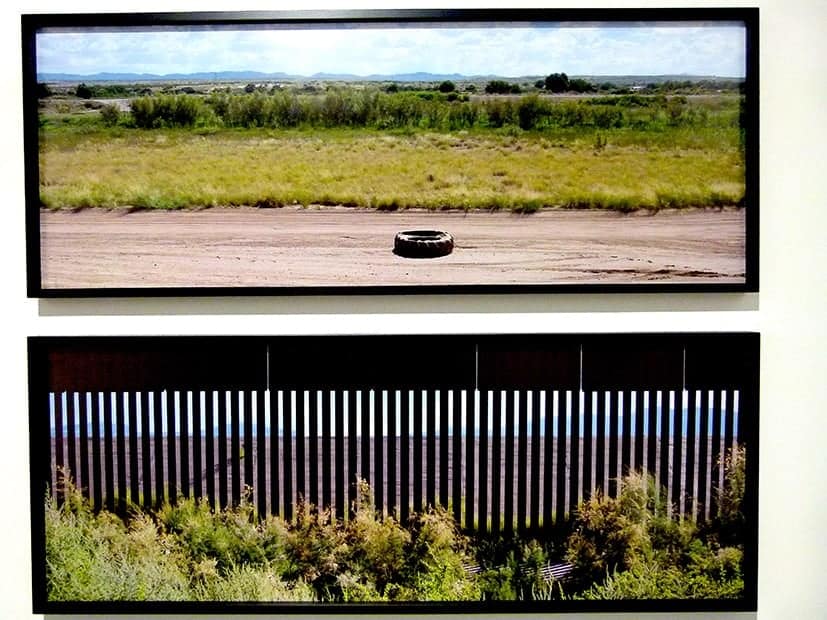

Continuing with this current and morally important theme of immigration, the medium of photography was used to great effect by Willie Doherty. His stark photographs At the Border -In-Between (Tread Softly, Breathe Gently) Fabens Texas (2017) and At the Border, Neutral Zone (Don’t Look Back) Fabens Texas (2017) featured the Texas border area between Mexico and the US, exploring the fraught histories and narratives of this terrain:

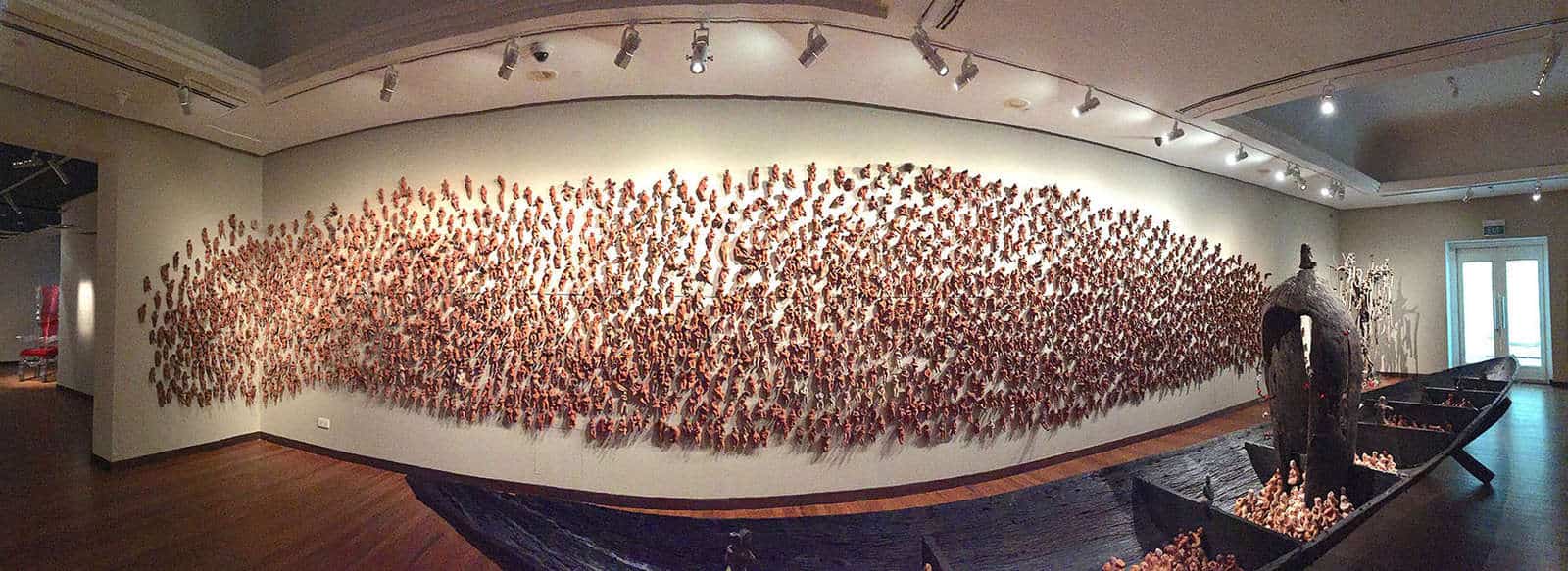

In contrasting these works with Indonesian artist Made Djirna’s Melampaui Batas (Beyond Boundaries) (2016) which I had seen at the last Singapore Biennale, I wondered about the role of hope in the story of migrants.

Clearly, the conversation on migration is moving forward from all sorts of places, be they Western, Asian or anything in between. While I wouldn’t wish to dwell on universalist theories of art which presume that great art appeals to a kind of fundamental human condition, there is something to be said about the thematic congruence between the display at Art Basel Miami Beach, and the works which I had seen exhibited in Southeast Asia. Indeed, there is power in this resonance, in this melting of boundaries between East and West, North and South, the “powerful” and the “weak”.

Another example of how globalization has reinforced change came from the Tyler Rollins Gallery, a gallery which bills itself as the “only gallery in the US with a primary focus on cutting-edge contemporary art from throughout Southeast Asia.”

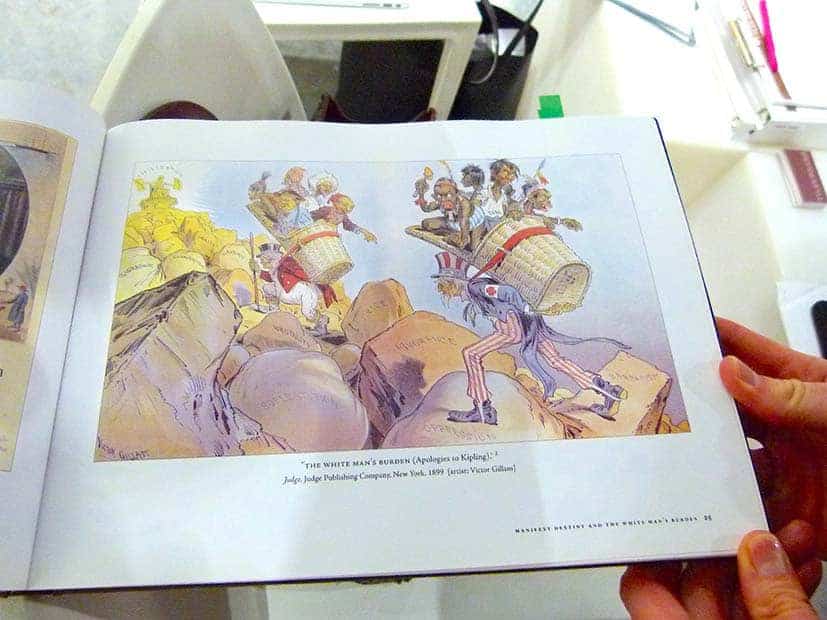

The works of Manuel Ocampo showcased by the gallery provided a timely history lesson to us all. The American Philippine War 1898-1902 was a costly early foray into colonialism by the US. Justified variously by military concerns, trade issues and an American interpretation of that colonial cliché the “white man’s burden,” the vote to annex the Philippines passed the US Congress by only 1 vote. Therefore, the political and editorial cartoons that were published at the time, were used to support the annexation.

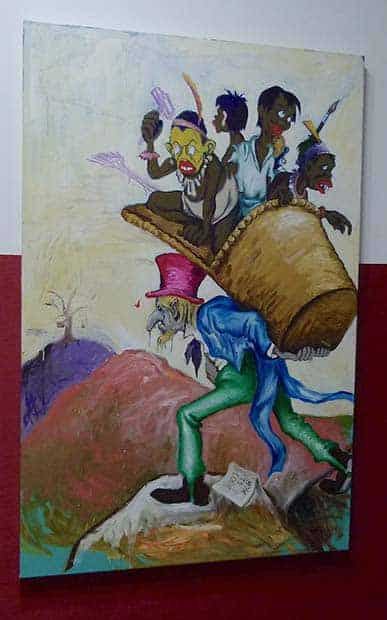

I especially enjoyed the way Ocampo reimagined these cartoons and added layers to make them resonate with present-day circumstances. In one image, Uncle Sam’s facial features had been altered and bite added by a manuscript notation. The faces of the ‘savages’ were also changed:

To me, the danger of forgetting or rewriting history was made evident through this work. Again, I was confronted with an artist from another place offering direct, and cogent comment – as an equal not an “Other.”

It was so exciting to see such a variety of work and to feel the transition towards the viewing of art created outside of traditional centres of power. Works from places historically seen as the “Other” seemed to simply be work from another place, presented on an equal footing with all other pieces on display. Is this a trend which is gaining momentum?

I certainly hope so.