If you’re looking for an antidote to the Kevin Kwan fever that’s gripped our region, and you’re based in Singapore you might want to think about attending the European Union Film Festival’s (EUFF) offering on 15 May, Fragments. It’s a gritty collection of 13 short films with a specific Southeast Asian focus and attempts to explore the struggles faced in each of the region’s component communities.

Fragments (and indeed, the entire film festival which begins on 10 May) will be screened at the National Gallery Singapore. I was invited to review the film ahead of its release and was immediately struck by the thematic similarities in the subject matter addressed in it, vis-a-vis the issues which emerge whenever Southeast Asian modern and contemporary art is discussed.

So, here’s a review of Fragments, as presented through the art presently on display in the Gallery’s Singapore and Southeast Asian permanent collections.

The Rural-Urban Divide

Rapid urban development in Southeast Asia has led to asymmetries in wealth, status and power amongst its communities. A 2014 World Bank study, for example, makes the following observations about Vietnam: by 2013, Vietnam was estimated to have 110 “super-rich,” defined as persons holding assets of US$30 million or more excluding a principal residence. This was a substantial increase from just 34 super-rich in 2003. While the World Bank further explains that neither the number of super-rich nor the growth rate is extraordinary for Vietnam at its income level, it also cautions that perceptions of inequality are growing, especially since ethnic minority groups which make up 15% of the country’s population, account for 70% of the extreme poor. According to the report, poverty in Vietnam is concentrated in northern areas of the country, as well as in the border areas of its south-central coasts, and in parts of its central highlands.

These sobering statistics play out on screen in Phan Dang Di’s Rain, a clip about a factory worker and his girlfriend, who run into their boss’ wealthy son while seeking shelter in an expensive hipster café. What begins as an unexpected meal during inclement weather, quickly turns into a moral dilemma that left me squirming uncomfortably in my seat. The exaggeratedly industrial and run-down quality of the café in which these characters first meet offers a sad parody of the simple lives led by the protagonists:

A glimpse of the difficulties faced by Vietnam’s poorer communities can be seen in Tran Luong’s video work Mao Khe Coal Mine Project found in the vicinity of Galleries 14 and 15 of Between Declarations and Dreams. Tran collaborated with 10 other artists who travelled to the northern Vietnamese coal mining town of Mao Khe, in an attempt to record and comprehend the problems faced by such mining communities. Performances and workshops were conducted with the miners and their families, and as Gallery curator Adele Tan observes:

“although overt political judgment was withheld in the video, the visceral quality of the miners’ blackened bodies and their precarious working environments told of the failings of the Socialist dream to uplift the living conditions of all Vietnamese.”

The issues in Mao Khe, and in the film Rain are crystallised beautifully in the lacquer painting Buddhist (1993) by Truong Tan, which illustrates the artist’s views on the conflicting elements of Vietnamese life:

The left panel shows “a traditional world, with ascetic figures embodying traditional Buddhist principles of self-discipline and the denial of indulgence,” while the right panel depicts the material world. The painting offers the view that while the two worlds appear to be conflicting, they are nonetheless “equal realities which can only be experienced in relation to each other.”

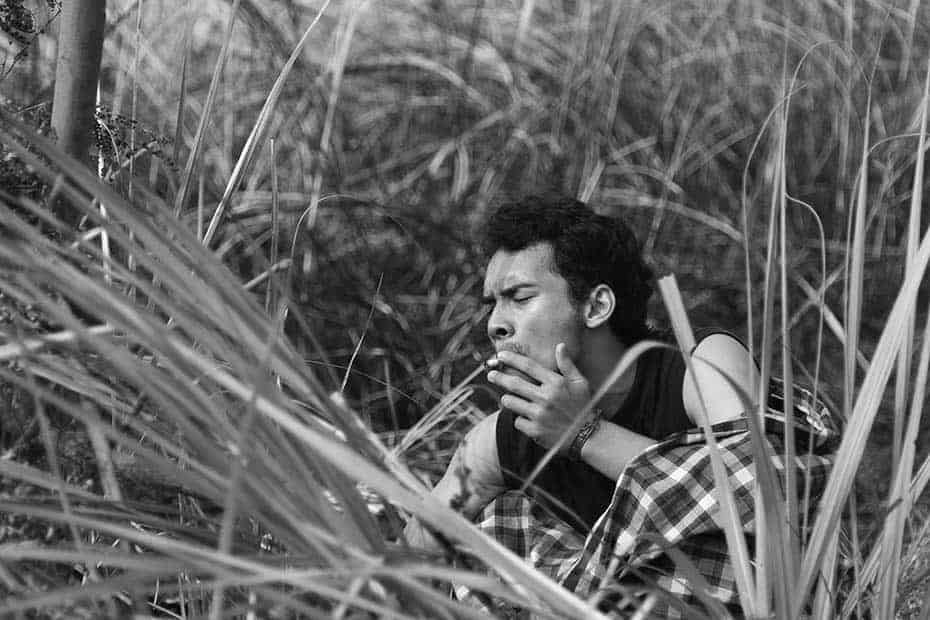

In a similar vein, Lucky Serwandi’s short film Serpong features a tragi-comic search by an impoverished Indonesian street-food seller and his wife for a place to relieve themselves after she chokes up their squatting toilet with her menstrual pad. It offers an incisive look into the rich-poor divide in Indonesia.

Despite being filmed in black and white, this clip is awash with graphic imagery of human bodily functions and emissions (for example, faeces, menstrual blood, food, the act of relieving oneself, clogged toilets, sex).

I’ll be honest, I had some trouble keeping my lunch down while watching this film. A shopping mall in Serpong, acts as a kind of shiny mecca, calling out to the beleaguered couple, who end up getting all dressed up just so they can access the fancy building in order to use its facilities and relieve themselves. While dreaming of their future unborn children, the street-food seller wistfully hopes that his son might one day be a security guard and that his daughter might be beautiful enough to work as a sales promotion girl or SPG.

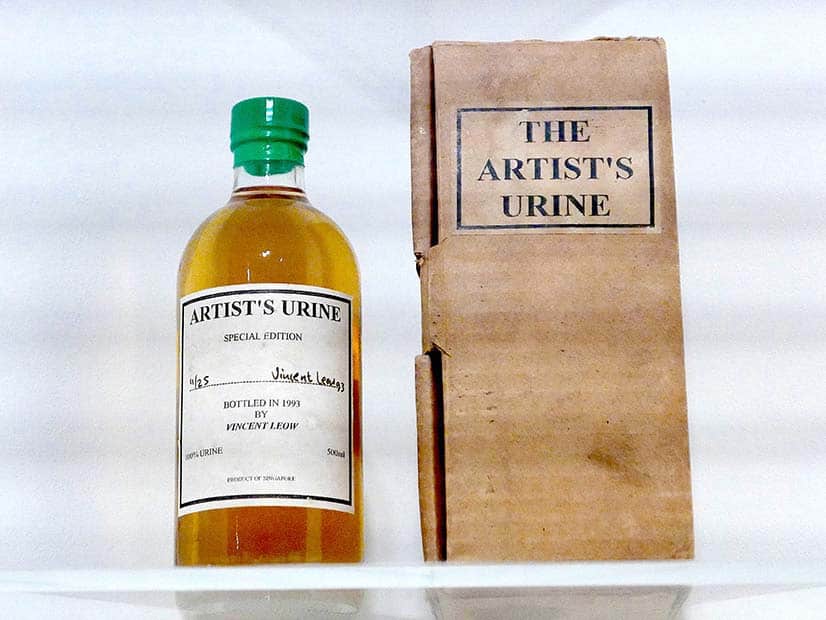

Speaking to the scatological themes in the film, this review would be remiss if it excluded Vincent Leow’s The Artist’s Urine (1993-1994), displayed in the DBS Singapore Galleries:

In a 1992 performance work, Leow drank his own urine. He then proceeded to bottle and distribute the stuff, in an attempt to challenge society’s desire for the acquisition and consumption of all things scandalous and controversial. The veneration of human urine as an “art object” in the Gallery offers a thought-provoking contrast to the difficulties faced by the protagonists in Serpong who can’t even afford to have their toilet repaired. It made me think about the things we take for granted in shiny, efficient Singapore and of the relative values placed on objects and needs, as societies progress.

The Chinese Diaspora

The Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia is poignantly addressed in Fragments, through Sherman Ong’s The Warm Breeze of Winter which sees a young Chinese woman returning to Malaysia where her mother had been born, to unite her mother’s ashes with those of an old Malay lover.

The longing of the mother to return to her true home in Malaysia while her “heart withered away” in China, is beautifully juxtaposed against Wesley Leon Aroozoo’s PRC- turned-(almost) New-Singaporean expectant mum, and her experiences in modern-day Singapore.

Aroozoo’s film, Umbilical, takes a bittersweet and humorous turn, cutting to scenes of the woman’s unborn twin fetuses, who appear to be wholly local, and who react according to how their mother feels when she is ostracised by Singaporeans:

I was instantly reminded that xenophobia has no place in Singapore as we have always been a migrant society, and richer for it. Nothing exemplifies the value of syncrecity more than the modern artists of Singapore who depicted Malayan life in their Chinese ink painting:

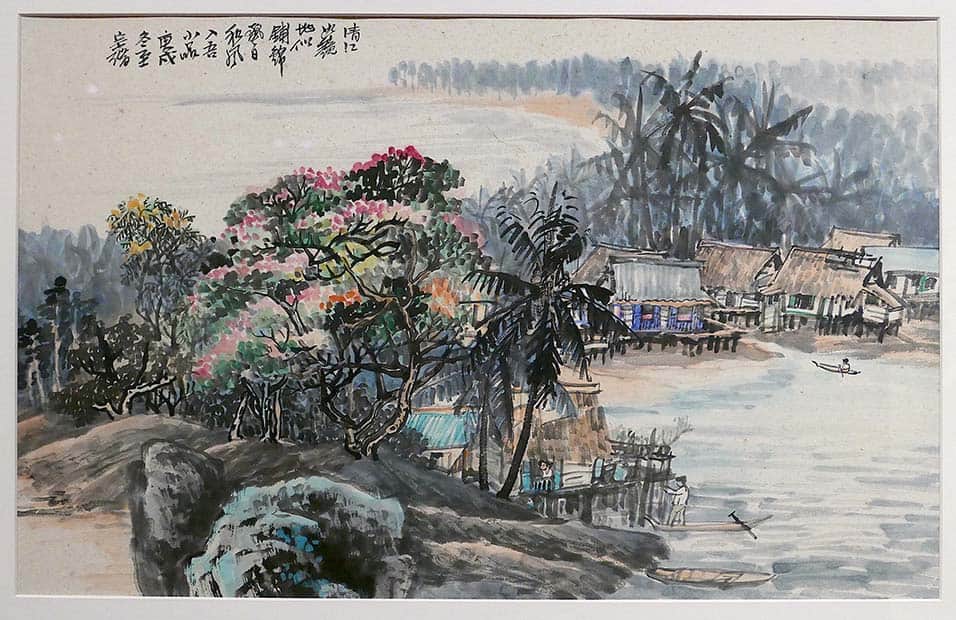

Here’s Chen Chong Swee’s Kampong (1970) for example, which represents an entirely un-Chinese subject, the Malay village. It’s an approach which localises Chinese ink painting, reminding viewers of the multiplicity of ways to be “Chinese” in the region.

Abstract Sensibilities?

U-Wei Haji Saan’s film Satu Note Satu Fragment (One Note One Fragment) frankly confounded me. Spoiler alert, but the entire film involves an actor running around an office, and eventually large sections of a Malaysian city, which has been entirely abandoned by its inhabitants. At the end of the film, he simply receives a note and text messages stating that “everyone hates him,” (and presumably that’s why they’ve all left him).

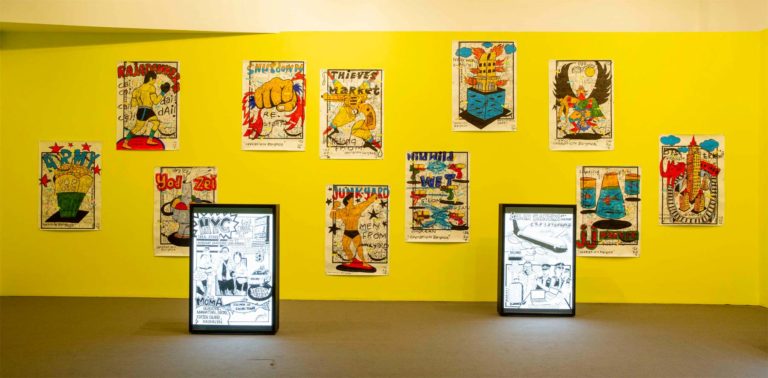

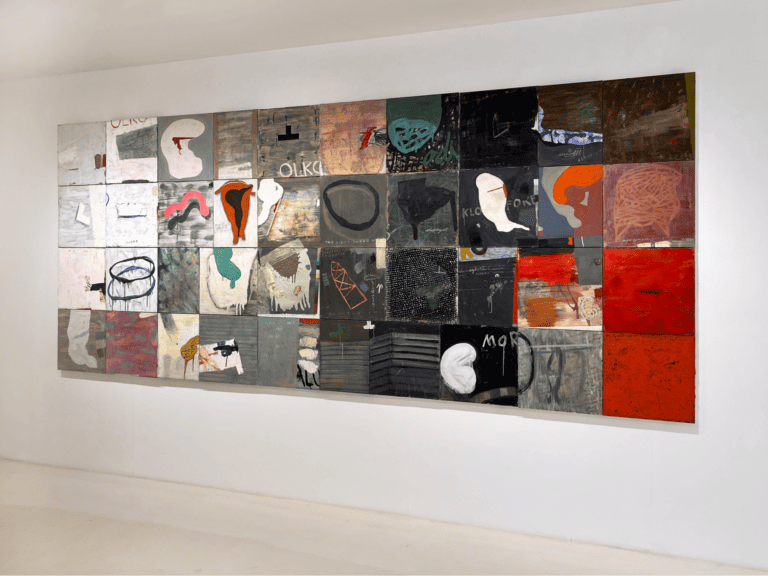

While I personally struggled with understanding this particular film, it absolutely reminded me of these ultimate displays of “nothing,” at the Gallery:

Here’s Cheo Chai Hiang’s 5’ X 5’ (Inched Deep) (1972), which is literally an empty (but demarcated) bit of space in the Gallery:

Cheo’s work was an early example of conceptual art in Singapore, having first been submitted to the Modern Art Society, as a proposal in 1972. It was subsequently rejected and the society’s founder Ho Ho Ying wrote a letter to Cheo setting out his reasons (primarily that he had found the work to be devoid of substance). That letter itself became an artwork of note, Dear Cai Xiong (A Letter From Ho Ho Ying, 1972) (2005), having been reproduced by Cheo in an installation which is now part of the Singapore Art Museum collection.

MIKE by Lim Tzay Chuen is also the documentation of a non-event, specifically, an attempt by Lim to uproot and ship the 70-tonne statue of the Merlion to the Singapore Pavillion of the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005. His request was denied by the Singapore Tourism Board, the custodians of this mascot of tourism. Lim then commissioned designers to transform the pavilion into a pair of grand public lavatories together with a signpost which read “I wanted to bring Mike over.” “Mike” had been the codename used by the artist for the project, in an attempt to keep the idea a secret during the early stages of planning:

If these works fascinate you, you may well be equally enthralled with the film Satu Note Satu Fragment!

And there you have it, if you’re up for an afternoon of Southeast Asian art and film, join the EUFF for its screening of Fragment on 15 May at 6.30pm.

If time permits, we’d suggest a quick wander through the Gallery’s permanent exhibits, before the screening. The art truly complements the film and beautifully rounds off an invigorating venture into Southeast Asia.