(Re)collect: The Making of the National Collection, with that emphasis on ‘re-’ as a double entendre on the art of collecting and the act of remembering, traces and examines the history and evolution of the National Collection. In highlighting how donations from art philanthropists can influence and shape its collection and direction, impact its legacy and burden to (re)present, it’s interesting to keep in mind other similarly-placed museums, such as the newly established M+ Hong Kong (with the impact of Uli Sigg’s large donation), or looking back further, how the Guggenheim New York was influenced by the eclectic collection and involvement of Solomon R. Guggenheim and other key individuals).

Appropriately, the entrance to (Re)collect spotlights the dashing figure of Dato Loke Wan Tho, a prominent film entrepreneur who built up the Cathay organisation in the 1950s and ‘60s. He was a major patron of the arts with a broad range of interests, including photography and ornithology. Educated in Switzerland and the U.K., he returned to Singapore when World War II broke out. When it ended, he focused on rebuilding the family concerns in film and cinema. As a public figure, he wasn’t reticent about mounting the podium to advocate for government and public support for the arts. The vanguard and raison d’etre of the National Gallery Singapore are surely animated by the spirit of Dato Loke’s rallying cry, “If you like a picture, don’t just admire it, acquire it.”

Dato Loke’s donation of 110 works in 1960 started the visual arts cluster of the National Collection, which in its entirety now comprises 280,000 objects, 10,000 of which are artworks. Over 8,600 have been transferred to the custodianship of the Gallery. 110 works, compared to the rest of the collection, might seem modest, but it was amplified by Dato Loke’s ambition of starting a national art museum for Singapore. Sadly, he was killed in an aviation accident in 1964 and never saw his efforts come to fruition.

Wandering through the 120 works for this exhibition by focusing on acquisition strategy – which artwork is gifted, by whom, which inherited from the National Collection – produces an interesting inside story. An infographic tells us 61% of the artworks in the National Collection were donated, either through donor families and foundations, the artists or their estates. Overall, this makes for a sizeable contribution. The listing of supporters on show reads like an honour roll of who’s who, and there are many recognisable key players from the Singaporean art scene.

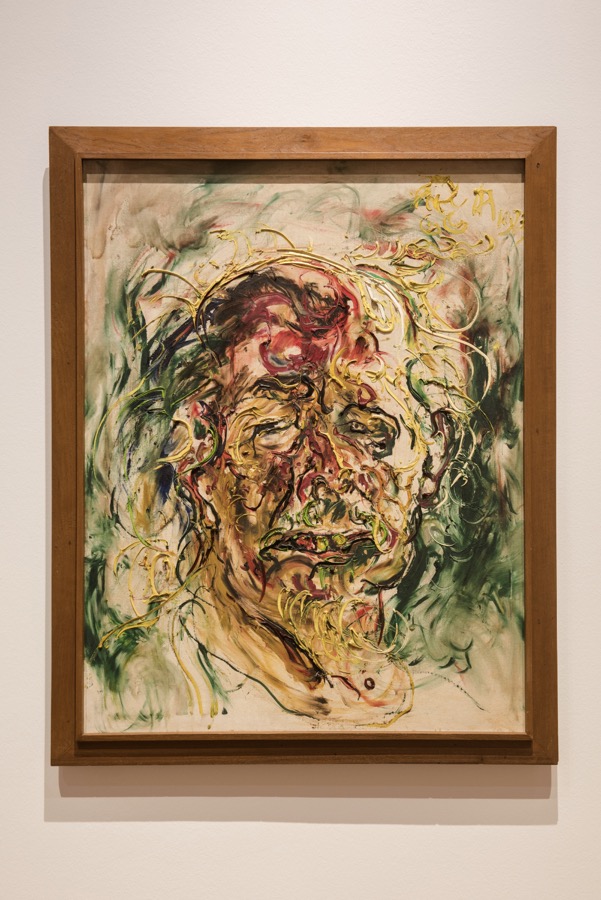

But donations by artists (two are given focus in (Re)collect – Affandi and Georgette Chen) – highlight a different angle, a more sentimental one. Chen’s Family Portrait, prominently displayed, is augmented by the contextual facts we glean from an accompanying glass display: it tells us Chen’s estate donated 53 paintings along with extensive archival documentation. The documentation includes a pocket-sized artist-diary full of her scribbles, photographs of Chen, photographs of her family posing with Family Portrait during a previous exhibition, her letters to friends and relatives that mention her husband, Eugene Chen’s internment by the Japanese, and her feelings of peace and calm upon settling in Malaya in 1960. Family Portrait was not a depiction of her own family, but of the family of Chen Fah Shin, a long-time friend. Georgette’s paintings after resettling in Malaysia concentrated on still lifes and tropical landscapes, scenes inspired by her surroundings. Altogether, the contextual circumstances and the relaxed intimacy and warmth of Family Portrait graft on a hue of nostalgia, a wistfulness about family, togetherness and the meaning of home.

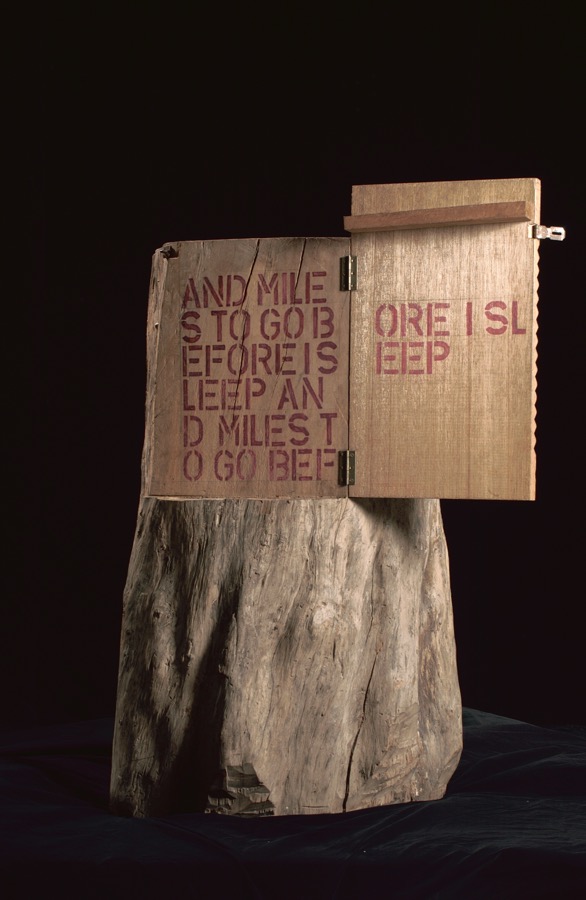

(Re)collect also features the histories of selected past exhibitions through which works came into the National Collection. The inaugural exhibition entitled Art 76 at the National Museum Art Gallery (NMAG), Singapore’s first museum, for example, showed Cheo Chai Hiang’s seminal work, And Miles To Go Before I Sleep, which was donated by the artist. Composed of found objects –a log (instead of a plinth) and a wooden laundry board that opens like a book, upon which was stenciled in red an excerpt from Robert Frost’s poem, Stopping By Woods On A Snowy Evening, the work pushed the boundaries of traditional sculpture and questioned the form a book should take.

(Re)collect provides an info-rama which, for me, was the linchpin to guide insights into the National Collection. The info-rama consists not only of the three case studies that show the amount of sleuth-work that goes into determining artwork provenance, but also a storyboard drawing of the acquisition process and key statistics about the National Collection. The infographic tells us 70% of the artworks within the National Collection are from Singapore, with Malaysia second at a drastically reduced percentage (8%) and Indonesia third (4.5%). When artworks in the National Collection were re-allocated between the Singapore Art Museum and the Gallery from 2012-2015, the Gallery inherited this breakdown. What this legacy brings up are a series of questions: how then should a museum address ‘lack’ in its acquisition strategy? Even within the largest bracket of Singapore, who are the ‘missing’ artists deserving of canonical status? What about the gender imbalance (a statistical breakdown deliberately not given by the infographic, possibly because it’s so skewed as to be meaningless)?

(Re)collect is the first of the Gallery’s series of exhibitions with the laudable goal of greater transparency and dialogue with the public. Chief curator Lisa Horikawa, in her email interview, reflected an assiduous institutional mind frame. She says, “we are [sic] constantly re-examining the canon by questioning what has been left out of the dominant narrative by identifying the gaps in the art historical narrative.” Within (Re)collect, we see several angles being addressed: the ‘lack’ in gender and regional representation, the ‘lack’ in photographic works, the links with Chinese ink painting as a diasporic art-form, and the newly-purchased artworks by the Gallery (signalling ‘turns’ in direction and purpose). Let’s look at each briefly.

Gender

Besides Georgette Chen, the Singaporean female artist canon as represented in the Gallery is indeed ‘lacking’. Hence, (Re)collect attempts to plug the gap through the acquisition of Kim Lim’s sculptural works. Kim Lim represents the Singaporean artist diaspora. Graduating from Slade School of Fine Art in 1959, she married British sculptor William Turnbull and settled in London, and her works manifest a preoccupation with space, light and rhythms. Accentuating her significance back in Singapore is a microcosmic exercise of ‘re’-collecting, ‘re’-investing, ‘re’-membering.

Region

The last section of the exhibition, housed in a different chamber, signifies almost a ‘break’ in acquisition strategy; it showcases Thai artists Montien Boonma, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Navin Rawanchaikul. Navin’s massive installation, for example, addresses the ‘lack’ in 3-D artwork representation within the National Collection. Entitled Asking for Nothingness, it’s comprised of 11,000 old medicine bottles constructed as 11 towers, each dusty bottle containing a photograph of an anonymous elderly, directly addressing the societal neglect of this demographic segment. In other material, the Gallery identified Cambodia, Myanmar and South Vietnam as a future regional acquisition focus.

Chinese Ink

With the large donation of 113 paintings by Wu Guanzhong’s family, the establishment of the Wu Guanzhong permanent gallery, and the 2016 exhibition of Chua Ek-Kay’s ink paintings, the Gallery pays heed to the numerous tendrils of connection in this diasporic art-form, through migration of artists to Southeast Asia, their early training within specific schools of ink painting, visits and exchanges, and of course, the emphasis given within NAFA, particularly in the early days of its founding. How the form, as practised by Singaporean ink painters, has evolved as a blending of different diasporic sensibilities is fascinating, one I follow with great interest.

Photography

Representing only 5% of works in the National Collection, photography is an acknowledged ‘lack.’ Only Lee Lim’s fine art photography is displayed in (Re)collect, however, although Dato Loke’s collection of photography is not insubstantial (unclear, however, whether it resides in the National Collection). Other connective strands emerge: Liu Kang, a pioneer artist whose body of work is being critically and contextually re-examined and deepened within the Gallery, was known to use the camera as sketchbook, even though he didn’t consider it worthy as an artistic medium. This link of photography to ink painting highlights yet another query: to what extent does photography’s low representation within the National Collection hark back to the NMAG collection strategy, under the leadership of Choy Weng Yang, of privileging ink painters, water-colourists, realist and avant-garde artists?

The candour with which the Gallery addresses its ‘lack’, making transparent where segments and regions are under-represented, is welcome, but what emerges is a taster to whet the appetite. Regardless, these are important initial footprints. Immense research and archival documentation (not previously a concern for NMAG) are required to deepen the connective links to reflect what the exhibition brochure calls ‘the complex web of art historical relationships.’ There are curious glimpses afforded into the art ecosystem of the 1950s and 1960s: for example, exhibition text tells us that Dato Loke procured certain of the artworks through Australian art critic and promoter Frank Sullivan, who as a patron himself, supported one of the Indonesian artists in the exhibition, Raden Mas Saptohoedojo, by purchasing art supplies for him and organising his first solo in 1949. Horikawa also revealed in her email interview that the Gallery is conducting deeper research into another key figure: Dato Loke’s secretary, Ann Talbot-Smith. How these relationships might have influenced Dato Loke’s collecting strategy not only illuminates various aspects of the Singaporean art ecosystem, but it’s a critical reflexive gesture that propels towards institutional research maturity. We await the many iterative possibilities to come.

Note: The feature image is a close-up of Navin Rawanchaikul’s Asking for Nothingness, 1995 – 1997, courtesy of the National Gallery Singapore