Today’s question is all about whether art is just for rich people.

Honestly, no, I don’t think that art is just for rich people.

Or rather, I want to believe — with every fibre of my being — no, not every fibre — I said I’d be honest, so let’s not exaggerate — with most fibres, or, rather, many — a large percentage, though not the majority — of fibres of my being are dedicated to the idea that art doesn’t just have to be for rich people.

But if I’m being realistic, well, then … it’s not so much art that’s just for rich people. It’s the whole eff-ing world. Let’s consider two, very telling statistics. In 2016, Oxfam reported that the 62 richest individuals in the world have as much wealth as the poorer half of humanity — that’s over 3.5 billion humans, thank you very much. Since 2010, the combined wealth of these 62 persons has increased 44% to US$1.76 trillion dollars. The wealth inequality in the world is staggering. It is not only unfair and wrong but, as some have argued, will cause both economic and political instability (see, for instance, Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, reviewed here by Nobel Prize economist Paul Krugman).

The second statistic cited above adds some important perspective. We talk about the 1% as if they are truly the elite. In New York City, if you earn close to a million a year, you’re part of that club. But what about the global 1 %? (That’s 76 million people, for those in need of a calculator). According to the Credit Suisse Research Institute, for the year 2016, you would have needed US$744,400 in total household assets, not annual income, to be part of that group. I should have written “only”, because that isn’t very much, come to think about it. It just goes to show how the upper middle classes of affluent societies are vastly privileged relative to the rest of the world.

But, okay, back to something drastically unimportant in comparison: art.

The problem isn’t whether art is mainly just for rich people, whether only they can afford or care to collect it — the problem is … capitalism!

Of course!

Capitalism explains wealth inequality, et cetera, et cetera. That’s a huge topic, so, for today, maybe we should just focus on the question of the price of artworks. My purpose is less to debate whether artworks are ultimately expensive or overpriced — and thus only for the rich — and more to do with the unpacking of the underlying conditions that determine their prices in the first place.

The market is, how to put it, not a rational mechanism. We know that the price of things very often has only a loose relationship to their value. We expect the fancy Rolls Royce Phantom to be much better than the Malaysian-made Perodua MyVi, one of the country’s best selling cars. But is it really more than 50 times better? In Malaysia, the Phantom will cost you at least RM 2.2 million, although you’ll still have to pay taxes on top of that. Whereas you can get a new MyVi for around RM 42,000. To be honest, when I went online to check prices, I was surprised that the multiplier was only in the order of 50.

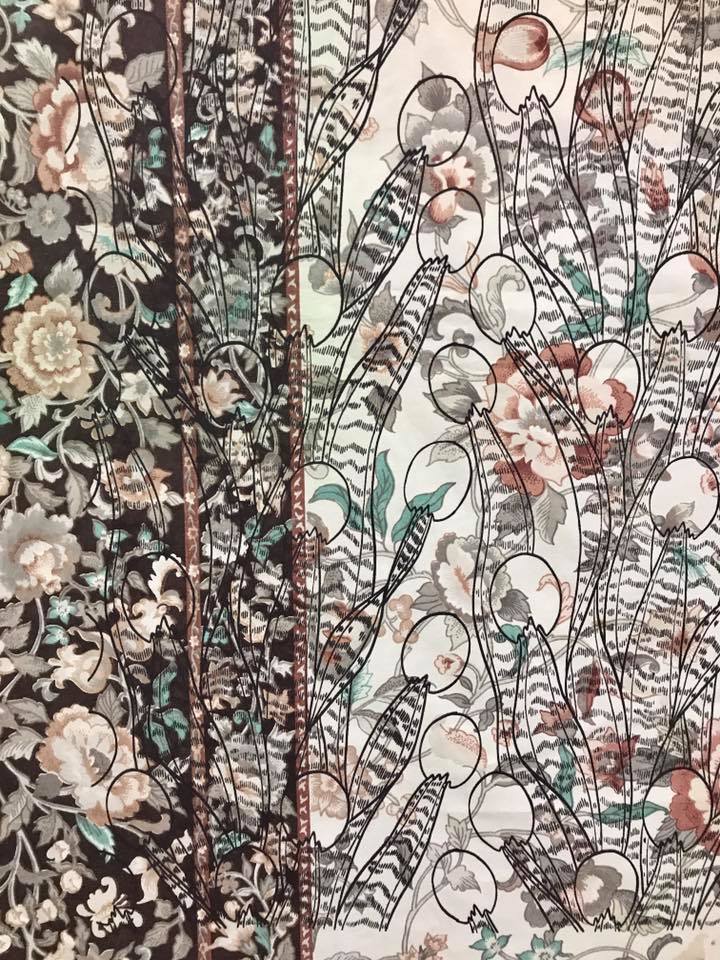

Looking at the market for art, here are a couple of random reference points: Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi recently sold for a record US$450 million at auction. Kara Walker, who last year entered ArtReview’s “Power 100” list at number 56, has had works featured on artnet.com in the price range of five figures. Sharon Chin, someone I’d consider an important contemporary artist from Malaysia, has sold collages on paper — four years ago — for less than US$1,000 each.

Rather than think of the price of the artwork in terms of the value of a commodity, let’s think of it instead as a form of remuneration for the labour of the artist.

Do artists deserve to be paid for their labour?

As is well known, a lot of artists resort to day jobs in order to sustain their practices — for instance, many teach. The majority of artists are not part of the upper middle class or beneficiaries of wealthy patrons. They work for a living. The majority may not be considered “great”, but most are dedicated to their craft, many do good work, and I’d argue that the world is generally better off because of their contributions to culture and society.

And I’d certainly argue that they should get paid — somehow.

Not every work an artist makes is made for sale, and so when that does happen, it’s helpful to think of the price as covering not only the particular piece in question but as a form of support for the artist’s entire practice. This puts into context why the price of a certain work may seem high in relation to what the object appears to be. For example, consider a situation where a limited edition work of ten photographic prints has been priced at US$10,000 per print. For the artist, let’s say that also covers a year’s worth of labour behind a major project shown at the Venice Biennale and that the prints were related to that hypothetical exhibition. If that exhibition was an event and site-specific installation, it would probably not be for sale, due to both practical as well as artistic reasons. Considered within this context, the US$10,000 price tag for each print may be easier to rationalise.

Let me end on a digression about tennis.

If you thought art was just for the rich, have a look at the inequalities in professional sports. We may tend to think of players like the stellar Serena Williams, who earned US$27 million in prize money and endorsements from June 2016 to June 2017:

But what about those who aren’t among the top 250 in the women’s circuit or the top 350 in the men’s — those are the players who earn enough to break even or better. That’s just 600 of the roughly 15,000 professionals out there in the world — the whole world. There are certainly more than 15,000 professional artists, globally.

These 15,000 tennis players are elite athletes, who have devoted their lives to the game, and yet the sport cannot seem to support them. It’s not enough to be among the top 5% of professional players worldwide to make a good living, let alone a lucrative one. You have to be within the top 1%.

Earlier this year, a report by an independent panel found that the sport is plagued with corruption, gambling and match-fixing at the lower levels.

For more than a few, that’s how they get paid to continue playing the game that they love. As it turns out, the financial structure of the tennis world is incredibly unfair. The very top athletes are not thousands of times better than 99% of their peers.

Isn’t this fact far more scandalous than that of all the match-fixing?