Everywhere in any city in the world, we find ourselves surrounded by signs; signs meant to sell, to attract, to tell us who we are, or what we should be. When artist Sin Many moved from Poipet – a small city on the border with Thailand – to Phnom Penh, all the new and flashing signs were overwhelming. It’s still hard for him to sleep in his apartment, with all the bright LEDs just outside. Critically looking around at his new city, these signs told him many things: that he should have whiter skin; that women were supposed to be sexy but also somehow still demure; he saw that he needed many more expensive things; he saw signs of sexism, overconsumption, tradition, and modernization, blurring into a dizzying array, often in competition with one another. He thought, I want different signs, signs about my beliefs, for the kind of community and person I want to be.

When we walk into Java Creative Cafe in Toul Kork, the first artwork we see is a series of light boxes made from screen printing screens. Half are blue, half are pink, and their simple line drawings explore rigid gender binaries in Cambodia. For example, the first piece we see as we enter is a broken plate, which speaks to the symbolism of fertility and virginity of vessels in traditional Cambodian culture. The piece was inspired by the painful experiences of Sin’s sister, who has two kids and no husband, a situation which is still frowned upon in Cambodian society.

The screens are grouped in sevens, making reference to a belief in Cambodia that everything – from poverty, corruption, to stupidity – lasts seven generations. While creating his work, Sin tried situate it in today’s world, while also being informed by events from three generations back, and trying to anticipate what will happen three generations in the future. At the center of the row, two prints of peculiar infinity signs are stacked on top of each other. They also look like menacing eyes, with one eye appearing broken. Maybe I’m just reading into things, but I wonder if it is a very significant local reference. I would never ask the artist to confirm this read, which speaks to the particular power of signs in Cambodia.

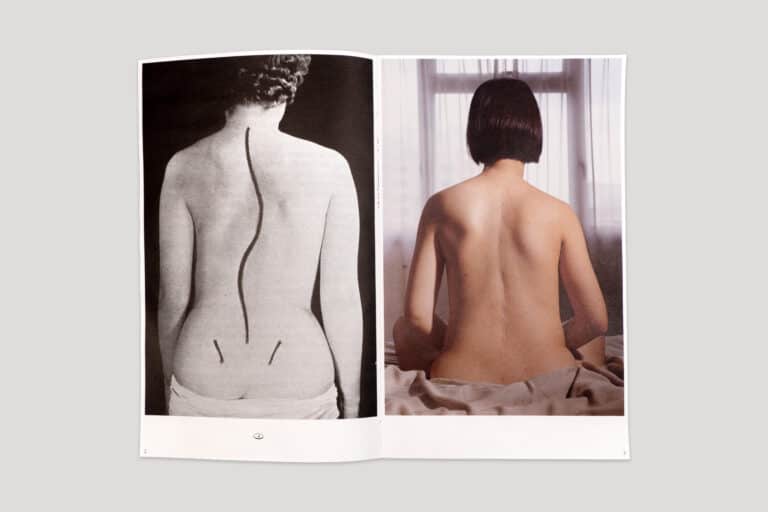

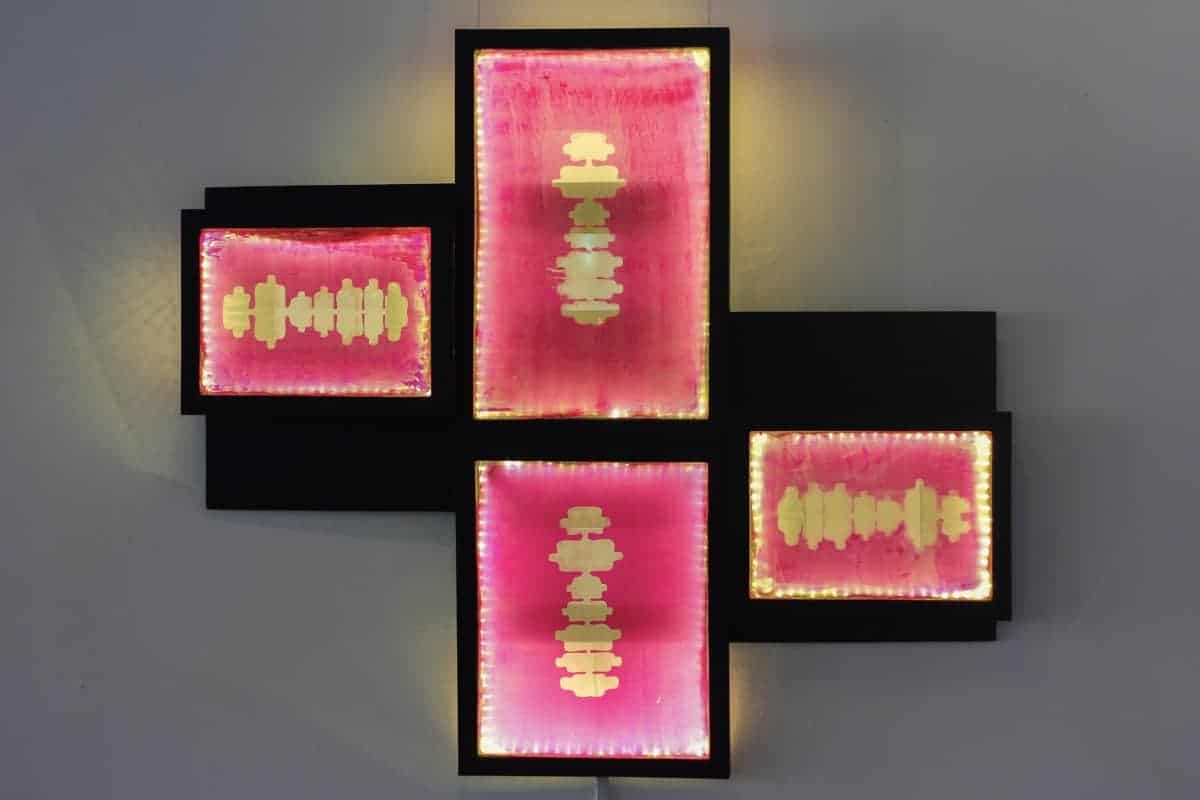

On the opposite wall are three impressive wall sculptures. While all deserve attention, I’m most drawn to Us (see image above), a series of four backlit screens, backdropped with black, and stacked together in a form of a broken crucifix or plus sign. The screens are suggestive of the human spine, but also appear as silhouettes, mirrored. Within the biological human form remains a multitude of personalities. This speaks to Sin’s interest in how the individual negotiates the society, and his questioning of any proscriptive construction of human “nature”.

Within some of the screens of Us, and throughout the show, mirroring and physical mirrors are a theme. The mirrors put the viewer into the work, into the signs, and ask that we test ourselves against society’s constructs, especially in the Cambodian context. The choice to use the screens instead of screen prints speaks to a process of reproduction and replication that move signs throughout society.

Curator and art space director Meta Moeng, who works as the Creative Producer of Java Creative Cafe’s project, Creative Generation, told me “I like the way that Sin experiments with his work, it is crucial to the process of how he thinks through and with materials.” Through a five-person jury, of which Moeng was one, Sin was selected for the solo exhibition as part of the Creative Generation’s effort to give emerging artists, designers, architects, or anyone creative a chance at their first solo exhibition.

In the exhibition text that Moeng wrote, she mentions Keith Haring as an influence, and I do see his deceptively simple line drawings as speaking to that history. I find especially lovely reverberations there considering Haring’s activism and art, especially artwork spreading the messages of the artist activist group Gran Fury during the AIDS epidemic, which ultimately killed Haring.

However, I also want to consider Sin in relationship with Cambodian-American artist Albert Samreth , whose solo exhibition in late 2017 at SA SA BASSAC, New Khmer Architecture, Sin helped to organize. I felt Samreth’s work looking at Phnom Penh, especially his stunning glowing blue acrylic window grate sculpture Vision A Reality (Wat Ounalom), 2017 was undoubtedly an inspiration for Sin’s work, especially in his work God, which also uses a window grate as form, but also in Us as well.

While both Haring and Samreth have a more developed aesthetic that Sin is still exploring, I’m deeply impressed with this exhibition for its deep investment in a conceptual and aesthetic exploration, as well as responsiveness to the limitations of the space. While this is Sin’s first solo exhibition, I’m certain there will be many more to come. As Sin subtly confronts what is rigidly constructed as “True” or “Moral” in the Cambodian context, he creates signs towards a process of thinking about what kind of society we want to become.

Note: The exhibition is runs till 7 October, 2018 at Java Creative Cafe, Toul Kork 20A Street 337.