2018’s National Gallery blockbuster has finally landed!

Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. which opens to the public tomorrow in two locations at the National Gallery Singapore and ArtScience Museum is a celebration of all things, well, minimalist.

The term is commonly understood today to refer to plain and simple aesthetics with clean lines and free, uncluttered spaces. As an art movement, however, it was a little more complex. Gallery Curator and Deputy Director Russell Storer informed us that the “minimalists were never actually part of any fixed group, and many of them didn’t even like the term.”

In Storer’s view, in order to understand the artistic shift towards Minimalism, one needs to have a sense of modern and contemporary art movements all over the world, and how artists responded to changing aesthetic trends, to one another, and to contemporaneous socio-political movements. The National Gallery Singapore and ArtScience Museum have attempted to take on the monumental task of contextualising Minimalism as it was expressed all over the world, and how it can be understood in relation to Asia.

First things first though: How might you begin to approach this exhibition when the art simply doesn’t look like well, art?

Gallery Director Eugene Tan had this bit of advice:

“This is all about experiencing the work rather than thinking about what each of them means.”

Still feeling lost? Fear not, we’ve got you covered with our list of 5 must-see works at the National Gallery:

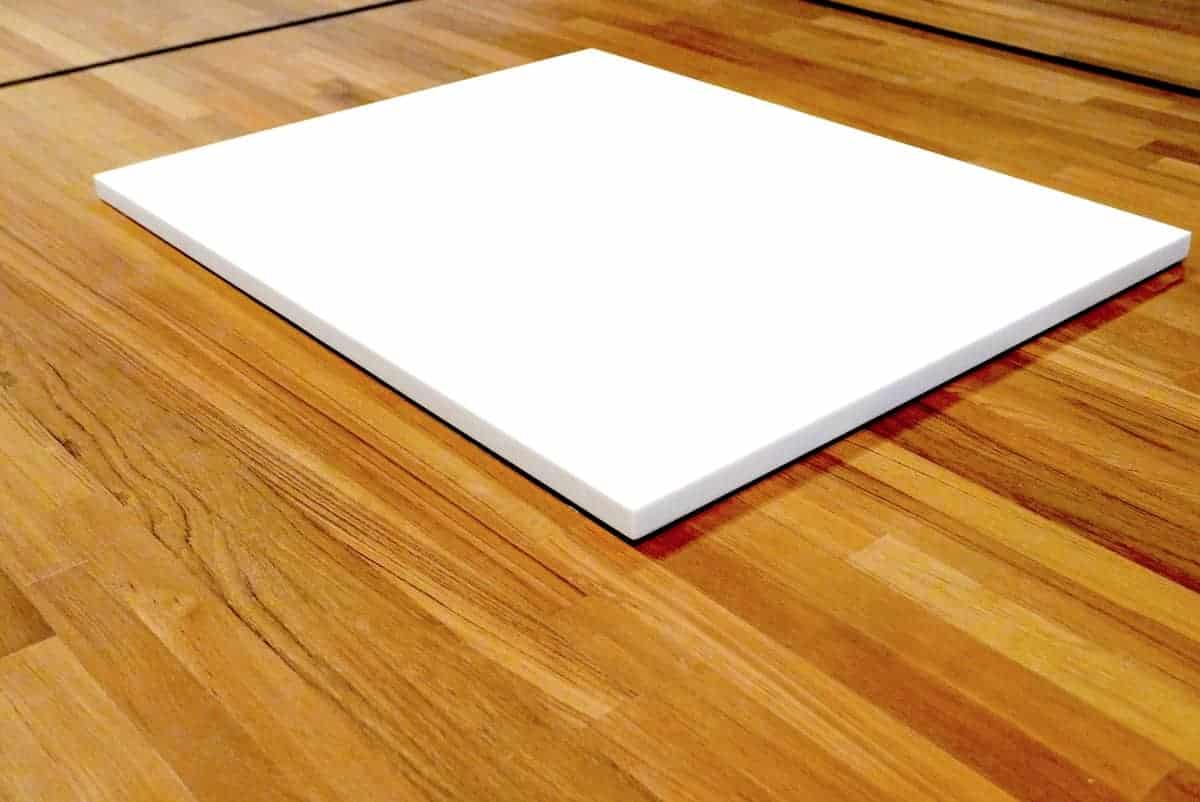

1. The White Square

Wolfgang Laib doesn’t want you to cry over his spilt milk, but instead, to have a think about your beliefs (or lack thereof) in the non-secular world.

This work is basically a hollowed – out marble slab which is filled up every day with milk. The hollow is so slight, however, that it is barely visible. The viewer is therefore presented with a shimmering square of liquid-covered marble that looks almost preternaturally reflective.

You’re probably thinking — how is this art again?

A good start would be to think about the significance of milk in Eastern religions – Buddhists and Hindus use it in their ceremonies and in particular the “feeding” of the marble with milk reminded us of this phenomenon, where Hindu temple idols were miraculously observed to “drink” milk which had been offered to them.

It is also interesting to think about the process of maintaining the artwork. The re-filling of the marble hollow has to be done each day as the milk sours after having been left out for a time. The cleaning up of the milk is itself a ritualistic process conducted in the same way, wherever the work is displayed. Curators need to follow a strict routine of mopping up the rancid liquid with a folded cloth, soaking up the milk, and then wringing it out. The process is repeated over and over again until the marble is clean. Laib makes us think about spirituality and ritual. Depending on which way you lean in terms of religious belief, you might find the work to be calming. Perhaps it is a physical manifestation of what peaceful meditation and ritual might look like if they were brought to life.

Or you might think it’s all ridiculous — a slavish kind of repetition to create something that’s essentially meaningless.

And that’s just fine too.

The point is really to have a think about what it could all mean and to form an opinion about it. When asked about how the act of filling up a stone cavity with milk might relate to more everyday acts Laib had this to say:

“Those stones were my first works after I had studied medicine for six years, and somehow they contain so much that is the opposite of what daily life is today…..(Art is to get you) not only to slow down but first to think about what you want for your own life, and also what you may want to change.”

What to say to sound clever: “This work is so deceptively simple. It’s making me think about going back to basics and living a less complicated life.”

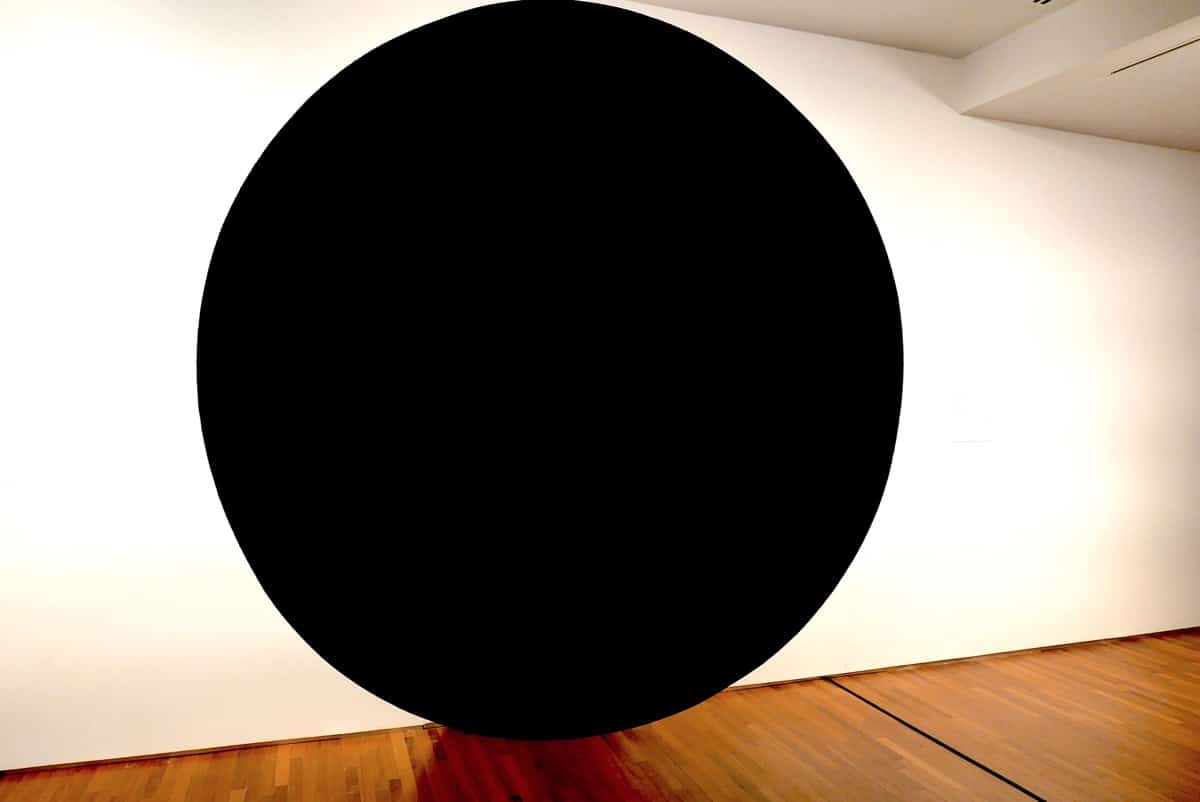

2.The Black Circle

So, there’s black, and then there’s Anish Kapoor black. In the vein of Yves Klein patenting the hue of International Klein Blue, Kapoor obtained in 2016, the rights to “Vantablack,” a pigment so dark in colour that it absorbs almost 100% of all light.

If that’s not confounding enough, what you see here seems to be absolutely what you get – this at first glance (above), is a black circle hung up in an art gallery.

Walk around the work and you’ll see that what appears to be black is actually a deep blue, and what appears to be two-dimensional, is actually not.

Why do we then care about it so much? Well, to put it simply, the black hole is not just a spot of absent colour, it’s a void.

Kapoor first started making Void pieces in 1985 and an excellent anecdote can be found here. In the display of one of his works in a dark bunker at documenta, Kapoor made a physical hole in the ground which was so dark it seemed to resemble a carpet. One angry visitor was upset at having been made to wait 45 minutes to look at (what he thought was) a single carpet on the ground. In a rage, he flung his glasses at the hole, only to see the glasses disappear into its blackness. Kapoor observed:

“And then he was truly terrified.

That’s what I am interested in: the void, the moment when it isn’t a hole, it is a space full of what isn’t there.”

The apparent universal appeal of Kapoor’s work also raises interesting issues about artist identity and notions of origin. Kapoor is India- born but resides in Britain and has commented that he gets “furious” when viewers attempt to find the “Indianness” in his work, asking him for example, if he’s used Indian spices in his work, which they are apparently able to smell.

You might remember an unfortunate incident this year where a museum visitor fell into a Kapoor work. Thankfully, there’s no chance of that happening here, as this particular void is safely propped up against a wall!

What to say to sound clever: “This has such a dense, rich colour. Staring into it makes me lose all sense of depth and it’s as though time is standing still.”

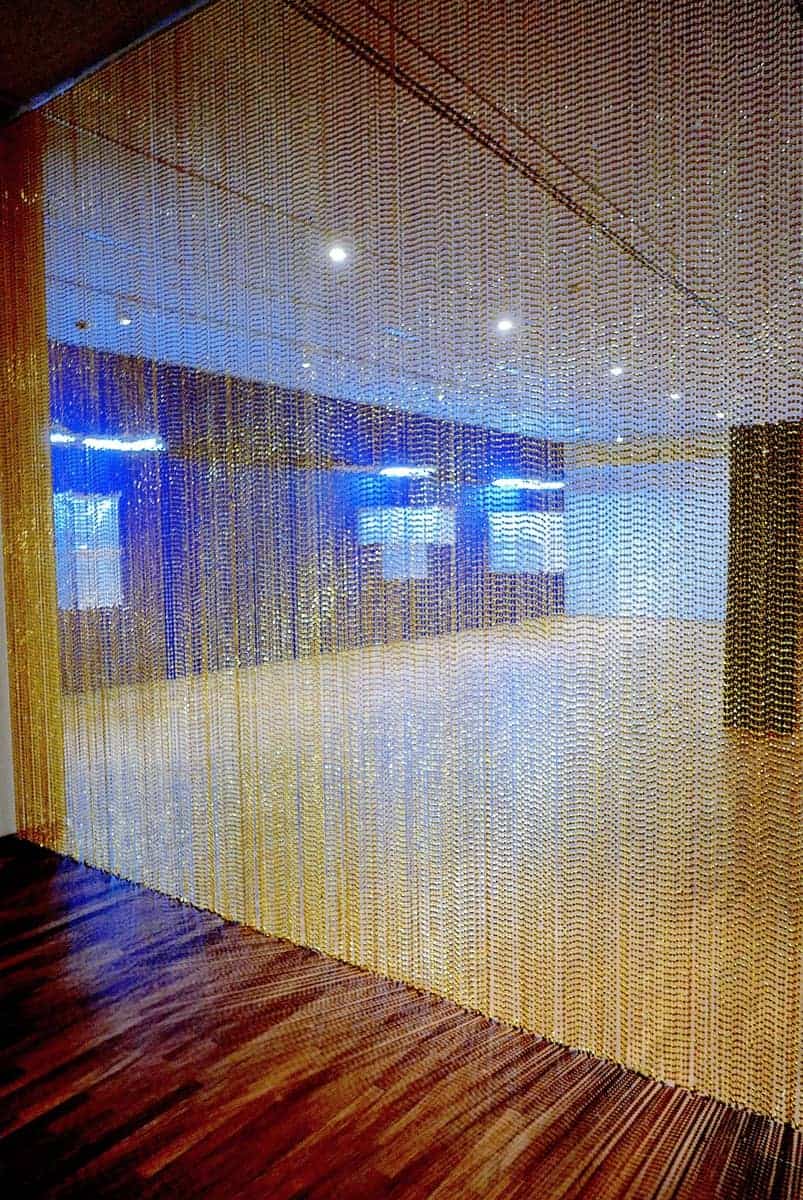

3. The Beaded Curtain

The beaded kitchen curtain is a ubiquitous object in Singaporean homes of a certain vintage. So what makes this one so special?

For starters – it’s big.

And golden.

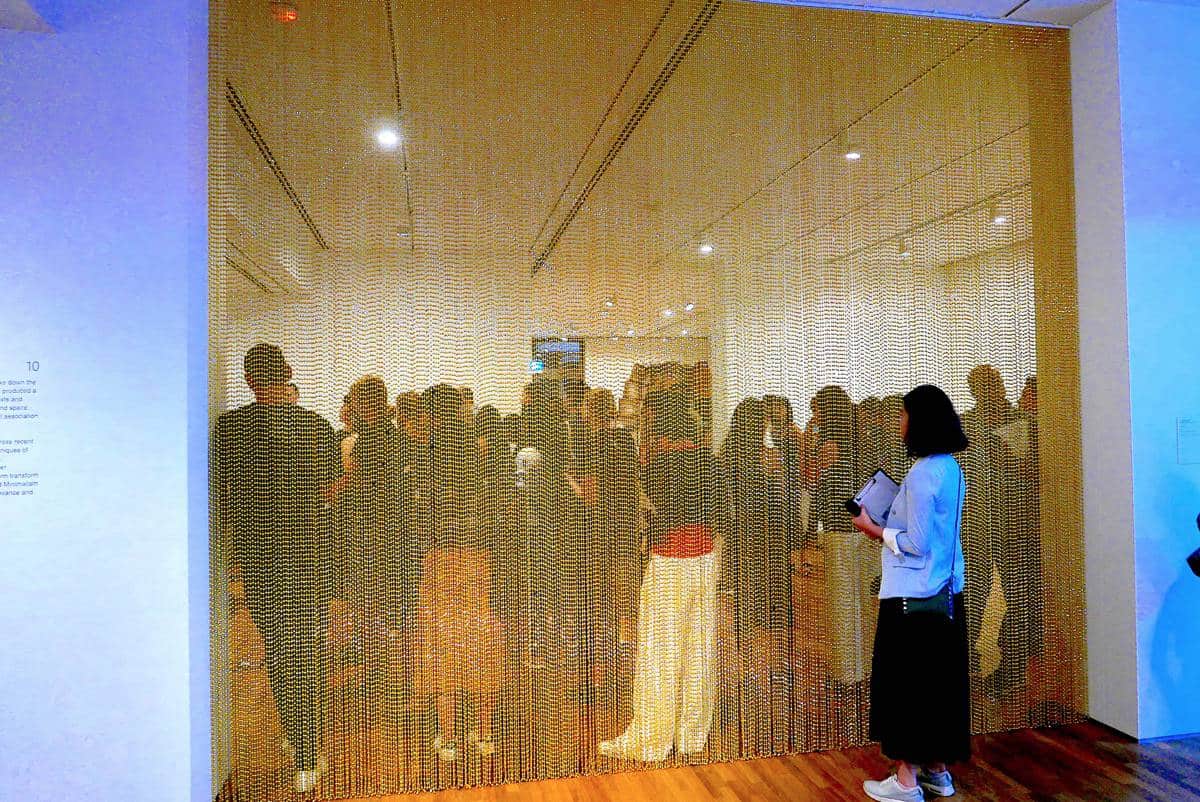

If that hasn’t grabbed your attention, maybe its symbolic value will. Tormented by the loss of his beloved partner to AIDS in a social climate which stigmatised homosexuality, Gonzalez –Torres’ curtain is meant to be touched and walked through. When the viewer does this, the shape of the curtain changes. Taylor Worley in a story for Curator Magazine has observed that the curtain is an article associated with domesticity, something which is usually hung in a bedroom, hotel or hospital.

Drawn curtains are suggestive of isolation – just look at how this single person below is removed from the crowd:

In inviting you to walk through his curtain, perhaps Gonzalez –Torres is asking you, the viewer to enter into his world and to try to understand his feelings of loneliness:

But before it all gets too serious, take a step back – this is, after all, a fun, swingy giant golden curtain. Is there a certain black humour to this?

Think about how kids and adults alike might play with the pretty structure — could the artist be making some kind of commentary on society’s fickleness and flippancy where the social issues of fringe communities are concerned?

What to say to sound clever: “One bead is insignificant, but a giant curtain of them has such weight and heft– it really brings home the point about the need for solidarity and empathy when canvassing for support in social causes.”

4. The Coloured Room

Ask any bright young thing in the art scene who their favourite contemporary artist is, and 9 times out of 10 you’ll find that Olafur Eliasson features in their answers. He’s a bit of an international powerhouse and definitely a name to know.

So what’s going on here?

You step into a room flooded with light from mono-frequency lamps- and then what?

Well, to put things simply, the light starts to change how you perceive things. In this room, everything you see is suddenly stripped of its colour and turns instead into shades of black, grey and yellow.

It reminds you that colour is itself not an objective thing and that things do not have any inherent colour. The colours that the human eye can see depend on how different wavelengths of light are reflected off objects and onto the retina. Light receptors in the retina transmit messages to the brain, which then interprets the colours that are seen. People who suffer from colour blindness for example, sometimes possess light receptors that are not fully functional and therefore are presented with a different impression of the world.

It may be science, but it’s all also rather poetic, isn’t it?

What to say to sound clever: “This room is such a great allegory for racism and colourism — we see simply what we want to see, or can see as a result of our individual experiences. There are no universal truths.”

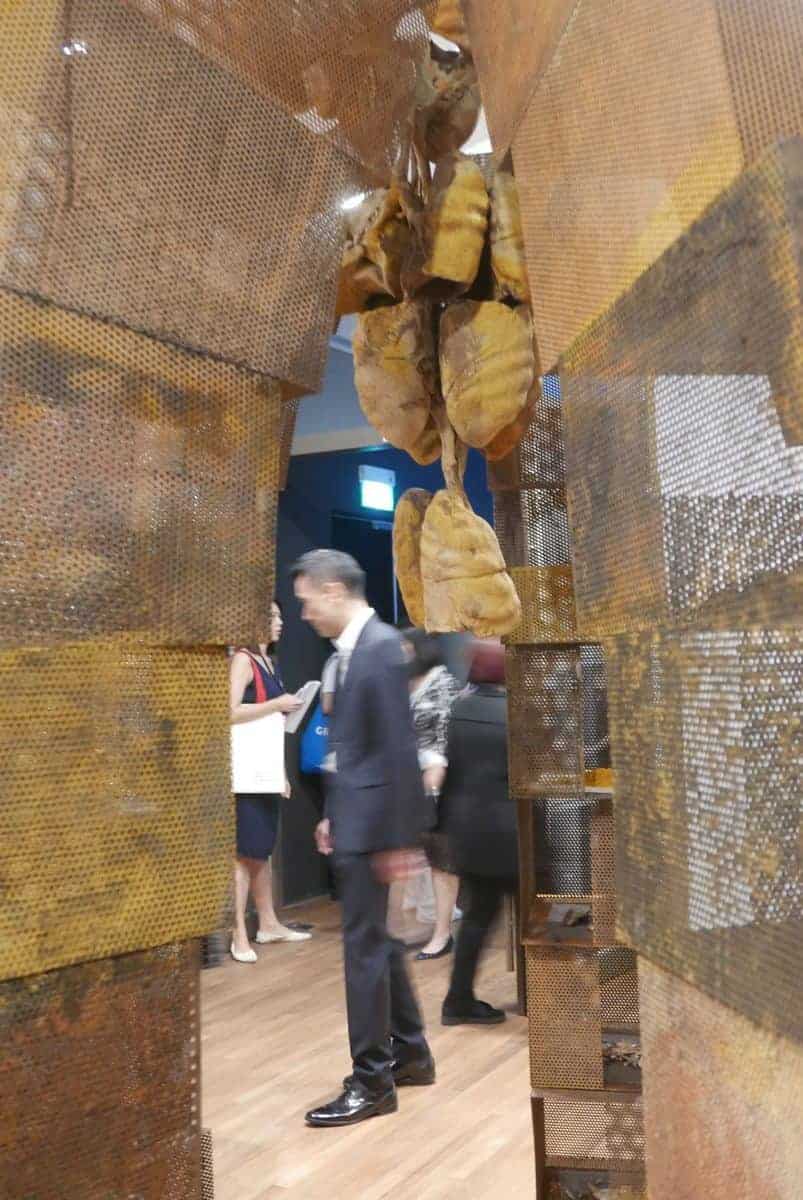

5. The Tower of Boxes and Herbs

This was a work that reportedly “took New York by storm,” when it was displayed at the Asia Society in 2003, some years after Montien’s death. This Thai contemporary art icon is well-known regionally for his practice which often incorporates ideas associated with Buddhism.

So what’s the deal with these boxes?

Montien’s work consists of columns made out of stacked metal cubes that curve inwards, an image which resembles dome-like Buddhist stupas. The columns support bags of medicinal herbs and their smell wafts strongly through the room.

The artist had a preoccupation during the latter part of his life with death and suffering and how they interacted with his Buddhist beliefs. He lived apart from his beloved wife for a period of 10 years on the advice of a trusted monk, during which time his wife contracted cancer and passed away. He too was to pass away of brain cancer some years later at the age of 47.

Small wonder then that Montien’s artworks have been described as “metaphors for hope, faith and healing, symbolising religious devotion and the possibilities of connection with the spiritual realm.”

What to say to sound clever: “Did you know that ‘Arokhayasala’ means ‘a place without sickness?’ ”

____________________

Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. opens to the public at the ArtScience Museum and National Gallery Singapore and runs till 14 April 2019.