We’re ashamed to admit that our usual geographical point of contact with the visual art scene in the Philippines is its capital city, Manila. Home to the Manila Biennale and Art Fair Philippines, the city is tremendously exciting and well-known to regional art enthusiasts.

We’ve also embarked on amazing art tours in Manila, like this one.

We were therefore intrigued to receive an invitation to feature Unrefining Sugarlandia, an exhibition presently on at The Negros Museum of Bacolod City in the Philippines. The show attempts to examine the complicated and bloody history of sugarcane plantations on Negros Island and features 23 artists. We spoke to Charlie Co (b. 1960) and Karina Broce Gonzaga (b. 1980), two participating Filipino artists from different generations, to share their views and impressions about the show.

Negros Island – An Artistic Centre?

When asked about Negros’ prominence as an artistic centre, Co explained,

“Art and culture have been present here in Negros since the early 1900s, when affluent local families would bring back art from their travels.

In the 1970s, art lovers and patrons would organize exhibitions, enabling Negrense artists to be exposed to Philippine contemporary art.”

He identified seminal art groups such as Pamilya Pintura, Art Association of Bacolod and Black Artists in Asia founded in that time, with several practising artists (including himself), being able to eventually penetrate the art world of Manila. He added,

“With the start of Gallery Orange–now renamed Orange Project–13 years ago by myself and local businessman Bong Lopue, and the recent renovation of The Negros Museum by the Negros Cultural Foundation, I believe we have given local artists a platform for them to bring their art to a new level, to be on par with artists from Manila and even the rest of the world.”

The Sugar Industry

The sugar planting industry in the Philippines has a long and complicated history. When the country’s American colonial masters took over in 1898, the sector was already a flourishing one. In fact, some historians point to this thriving industry as a reason why the Philippines had been so attractive to the Americans. In the 1850s, merchants from Iloilo city saw a collapse in their textile industry, which sent them searching for new business opportunities in neighbouring Negros Island. Peter Kreuzer in his report Domination in Negros Occidental: Variants on a Ruling Oligarchy explains that the indigenous tribal population of Negros was then driven into the mountains or exterminated, with the “fairly small number of lowlanders who had migrated to Negros in earlier centuries being submerged into a new frontier society dominated by immigrants.”

During the American occupation, the sugar industry continued to thrive, but with large amounts of wealth concentrated in the hands of the planters, who went on to become a wealthy and elitist class in Filipino society.

As with all financially lucrative industries, a new social order was built around economic concerns — that of the sugar plantations (i.e. haciendas ). These were run by the merchant landlords (i.e. hacenderos) in conditions that were often stifling and unbearable for sugar workers (i.e. sacadas). Anecdotes of oligarchic dominance and exploitation abound in writings about the history of Negros Island and its sugar industry. Kreuzer, for example, talks about trumped-up criminal charges being levelled against servants and workers, as imprisoned men awaiting trial – sometimes for months- were put to hard (and presumably free) labour, in the same manner as convicted criminals.

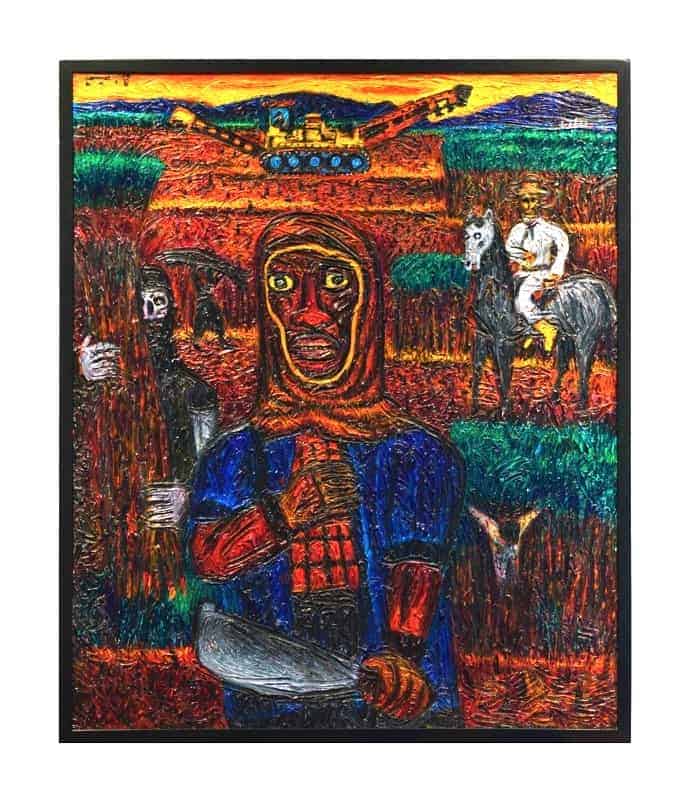

Roli by Charlie Co is a painting displayed in the Unrefining Sugarlandia exhibition, which was inspired by a colleague of Co’s (named Roli) who worked with him for 8 years:

As Co painted, he asked Roli to tell him what it had been like working in the sugarcane fields from the age of 12 to 16. Said Co,

“As I was painting, I tried to recreate the emotion. The major image in the painting is that of the sacada, because I acknowledge his sacrifices and the importance of his role in the sugar industry. But like it or not, the sugar industry is moving towards mechanization, which is more effective in remaining competitive in the global market. We cannot do anything about it…the sacada is a dying breed (and so) I painted the death face of the sacada to the left of the central figure.”

The whipping of workers was a regular occurrence and planters employed armed guards to prevent workers from absconding. Serge Cherniguin in his paper The Sugar Workers of Negros explains that sugar workers were not paid during May to September, the off-milling period which is referred to as tiempo muerto, or the period where one’s mouth becomes distorted because of hunger. Workers were historically paid in ‘rice advances’ to tide them over during this period, and were unable to grow their own food. With the practice of sugar monocropping, there was simply no land available for the planting of food crops to feed workers.

Cherniguin also points to various ‘soft’ forms of control, for example, the provision to workers of free housing on estates, which as he explains, “is a good incentive for an unorganized worker to work without complaint under inhuman working conditions.”

If a worker were to complain about low wages or join a union, he could then expect to face the loss of his home.

Women and children were not immune either from exploitation. Regardless of labour laws which were passed in 1935 to provide for a minimum wage for sacadas, the situation remained dire. Cherniguin posits that legal loopholes were exploited and wages were paid on a piece-work basis, a practice which resulted in whole families working together to maximise output, institutionalizing child labour and forcing women to work up to the last days of their pregnancies.

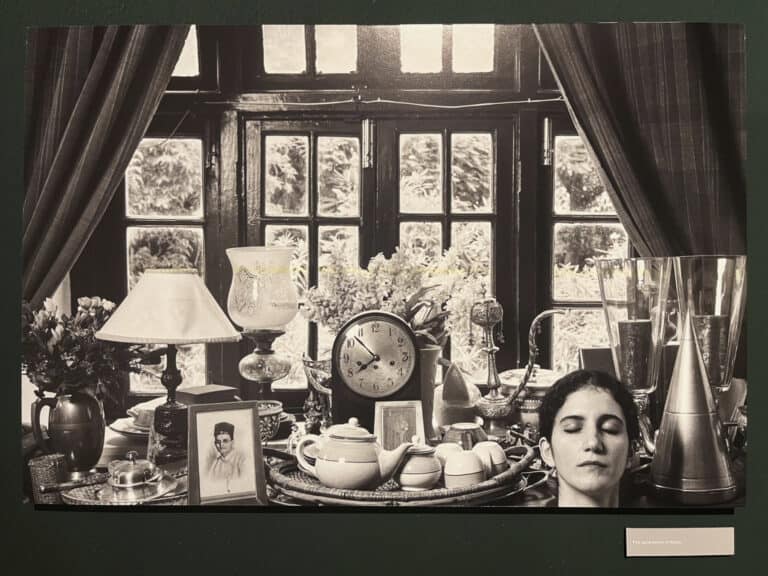

Karina Broce Gonzaga’s work in Unrefining Sugarlandia particularly references the condition of the female sacada.

Her artwork Blind Faith, for example, is premised on the idea that one year in a sugar farm seen 2 cycles of planting and harvest respectively, making for a total of 4 stages of growth:

In Gonzaga’s work, 4 female figures wearing veils, appear alongside one another on the canvas.

She explains:

“The young girl (on the extreme left) represents hope and innocence. The second figure is a teenager or in her early twenties as a sacada woman in the kampo (sugarcane field), she is now looking for someone to wed. The third figure is anywhere between 40 to 60 years old; she can have a 19-year-old and a one-year-old, and 8 children in between. She is the one bearing the weight of reality, in a sense. The last figure is that of an old woman, and all she can do now is pray.”

A similar aesthetic can be seen in Gonzaga’s Saccharine Plights, a 2018 work which was exhibited in an earlier version of the Unrefining Sugarlandia show held at Secret Fresh Gallery in Magallanes, Makati City, Philippines:

In both works, extraneous flowers and spots buzz around the subjects’ bare bodies like flies, recalling both images of decay and (rather incongruously) the notion of trapping flies with honey. When speaking about this work, Gonzaga displayed a nuanced and sensitive understanding of her own privilege. She told us,

“My good memories of my childhood in my grandfather’s hacienda were, in fact, based on other people’s lives that were very difficult, and I had no idea…So I came up with the image of sacada women whose heads were wrapped in their own t-shirts…almost like they were being suffocated.”

Both Co and Gonzaga point particularly to the guidance provided by exhibition curator Gina Jocson which according to Gonzaga allowed the artists to “dig deep into what we believed our home island means to us in relation to the culture and history of sugarcane planting.”

What did the artists hope audiences would take away from the show?

Co’s response is rather straightforward, hoping that viewers will learn all about the realities — both good and bad– of the sugar industry, and be able to see them from the artists’ point of view. Gonzaga meanwhile, shared this anecdote:

“A couple visited our exhibition one day. The woman, who was Filipino (and) her Caucasian male partner were touring the rooms. I overheard her explaining to him about the sacadas, the harvest seasons, the terms such as hacienda (sugarcane plantation), haciendero (sugar baron), etc. I couldn’t help but listen to her explain. Then I realized our exhibition had become an educational tool about our history. That, I found to be a cool outcome.”

_____________________________

If you find yourself in Bacolod City between now and 28 February and are looking for an educational pitstop, do visit the Negros Museum and check out Unrefining Sugarlandia.