“If I could take a poll of everyone who has cried in front of a painting, I would bet the majority do not have much contact with the art world at all. They don’t do their crying in museums, but in churches.”

–James Elkins, Pictures and Tears

I find solace in the solemnity of sacred spaces.

When I was in the sixth grade, I savoured a school field trip to the prayer sites of the major religions: a synagogue, a church, a mosque, and a temple. My spirited social studies teacher, a self-proclaimed freethinker, guided our class—a diverse crowd of third culture kids living in Singapore, coming from vastly different backgrounds and beliefs.

Before entering each space, we followed specific rules and rituals based on the tradition of each belief system, as a form of respect for the holy ground we were to walk on: taking off our shoes, washing our feet, or merely keeping silent in spite of being our restless, 11-year-old selves.

Coming from a devout Catholic family from the Philippines, I felt alien to these new spiritual sites and actions. Yet, I was awed and intrigued. I remember gawking at the rich colour and intricacies of the Hindu temple, where carefully carved sculptures of different deities overflowed and overwhelmed.

I was stunned by the bare, wide floor of the mosque—humbled by the act of kneeling down and praying so close to the ground.

I remember speaking to the man showing us around at the synagogue, fascinated by how he, too, believed in the Old Testament and kept its holy texts in a special, secret room. As I sat inside the Christian church, I gazed up at a bare cross missing the corporeal body of Christ—a distinct change from the crosses holding up a suffering Christ that pervaded the Catholic churches of my childhood. I learned that this absence was intentional, and meant to emphasize Christ’s redemptive resurrection rather than his death.

That day, I gained something invaluable and irreversible: a deep respect for the beliefs of others, with a new curiosity for the faith I had inherited. I had been taught by a non-believer that rituals were rich and alive with meaning, and the depths of these religions led to places not of violence, but of peace. Having experienced a slice of beauty from each religion, a deep-seated, lingering question arose—what then was so special about my religion? Why did I still need to believe in it, with all its strange ceremonies and poetic words of promise?

Growing up from a mouldable adolescent to an adult, I delved into a jagged, profoundly imperfect journey in my personal Catholic faith. As the God I knelt before at church grew real and intimate to me, my curiosity transformed into conviction. I began to see why that man in the synagogue protected holy texts with such solemnity, and why my grandparents chose to hang worn wooden crucifixes in their homes with joy.

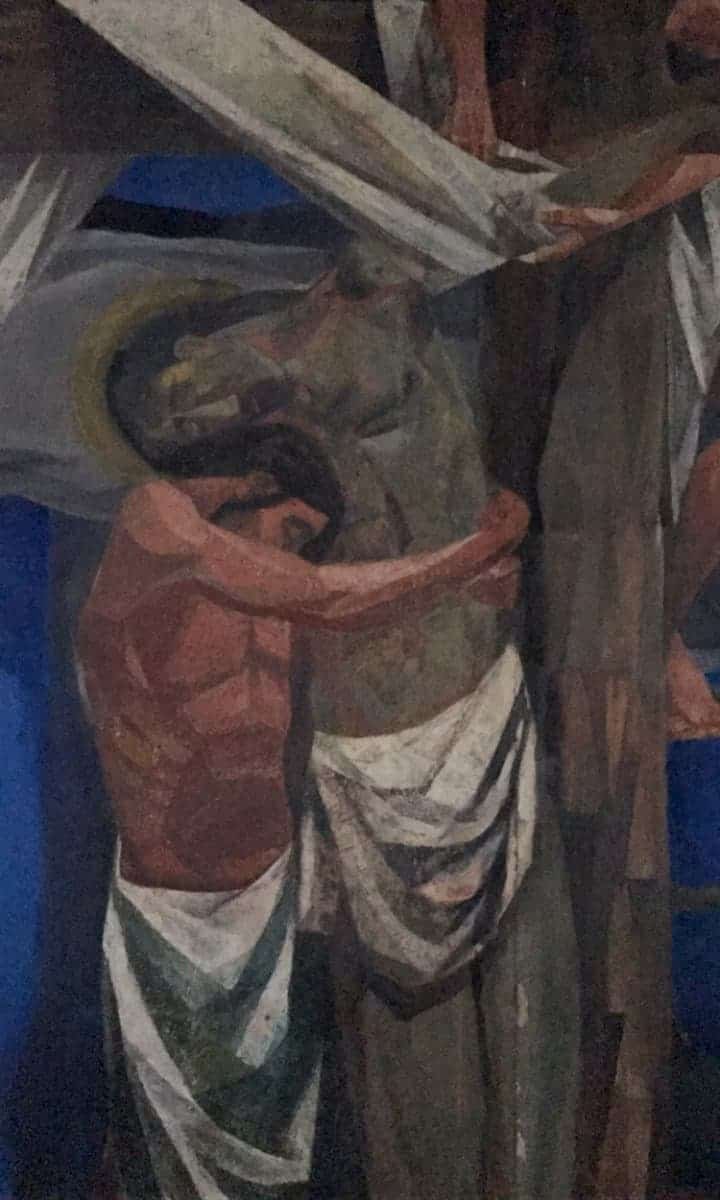

But, at the same time, I craved for the depth found in my faith in places beyond the walls of the church—I found similar solace in my innate attraction to art, and the dramatic ways in which it moved and challenged me. Moving from the college classroom to the museum to the artist’s studio to the gallery, I met and admired those who deeply believed in art—patiently caring for art pieces like blessed objects, and revering their makers like prophets.

Enigmatic yet alluring, these art encounters grew sacred to me—a time for when I would open myself up both mentally and spiritually, creating space for something to speak to me, consume me, dwell in me, and even, change me. Following my visceral pull to art, I eventually made a living out of describing works of art, considering my time spent at exhibitions to be almost as precious as my time at church.

Not too long ago, I found myself bewildered within the white walls of a gallery in Manila, attending a one-man show that I was curious to write about. Faced with fragments of memories that were not my own, I stood before objects and pictures that looked as if they had been salvaged out of abandoned homes:

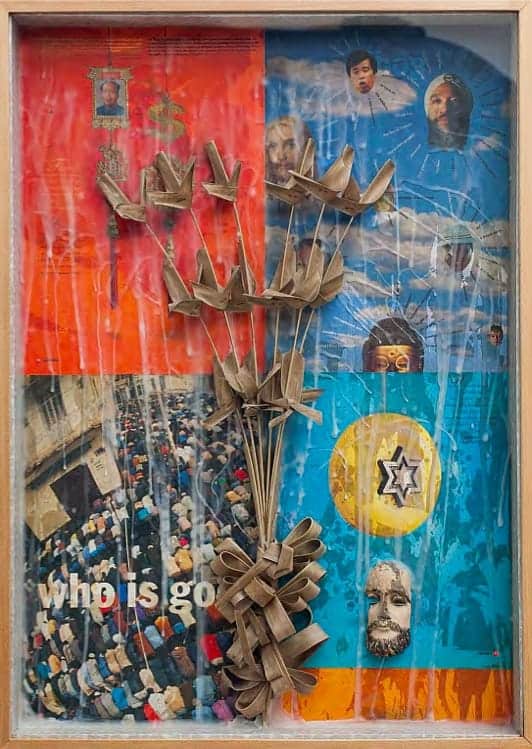

As I scanned the ambiguous arrangements of worn-out everyday objects, my eyes became glued to the divine icons and objects from Catholic traditions that were all too familiar to me: prayer cards printed with portraits of Jesus and Mary ubiquitous in the homes of my grandparents, wooden statues of saints particularly popular among the Filipino faithful and the palm branches I would hold up in praise one special Sunday a year.

One particular palm branch (see above), was glued against icons of ancient spiritual figures and a picture of worshippers praying in unison as they bowed down to the ground. In this collage, wax drippings evoking the candles lit during sacred ceremonies ran across symbols and scenes from religious traditions I had encountered as a young girl. Hollowed out and aloof, these images nonetheless called out to me—almost as if they had been plucked right out of my home, church and vivid personal memories.

Yet, set up in this manner, something felt different. I grew uneasy seeing the objects I would hold with care propped up there, on display for me to dissect as if I were a visitor in a museum of a faint future, speculating on the mythical beliefs of a lost age. As I confronted my faith in this light, the profound words and actions I had attached to these objects slowly lost their eternal weight, thinning out into ephemeral mantras and routines.

Days after this encounter, I began to write. I probed and grappled with why these objects had been depicted in this way, hoping that time might help me reconcile my thoughts. But, alas, the religious objects remained as they were: pieces of vague pasts radically removed from their contexts, floating and fading into cold, distant and dying memories.

By the time I finished drafting my review of the show, I had become so absorbed with these dead objects, that I had already stripped away the depths of the life and tradition from which they came. My own faith then emerged as the main object of scrutiny, standing out as the epitome of a sham. And in one brief and raw moment, the boundary that I had built for my sacred space—and the sacred spaces of others—shattered.

I began to see the faithful no longer as free human beings grounded in choice and conviction, but as puppet followers of void truths. I saw rituals and their objects as no longer rich with meaning and revelation, but as empty: constructed by the faithful out of desperation and bound to ruin and oblivion. And instead of being drawn by the complexity behind these symbols of faith, I became suspicious of them and most of all, conflicted and confused.

If I could believe all these traditions to be myth, were my own religious experiences purely make-believe?

In his book Pictures and Tears, art historian James Elkins writes that art can move people to tears roughly because of two opposing reasons: the first, because a work feels overwhelmingly full, complex and close; and the second, because a work feels “unbearably empty, dark, painfully vast, cold and somehow too far away to be understood.”

Unbearably emptied in that brief moment of realisation, I wept.

It pained me to realize that I had written about the God that I spoke to every day—someone whom I believed to be eternally living—in such a way that had cut him off from reality as if I had locked him up and imprisoned him into a ghost of the past.

I had to swallow the difficult truth that when we see and consume things, process them in our heads, and articulate what they could possibly mean to us, we are revealing a part of who we are, what we believe in, and how we have come to perceive the world.

I knew then that I would rather dwell in the colour and pulsating life of a temple, learn from those who humble themselves to the ground at the mosque and revel in the beauty shared between our faiths, with the man at the synagogue.

I knew that I would rather spend my time at my local church, crying before a painting that had meaning to me—before something that felt so full, so complex, and so close—than to lose what gave my life meaning and hope, and to cry over nothing at all.

Wrestling to recover what I held sacred, I erased every word I wrote.