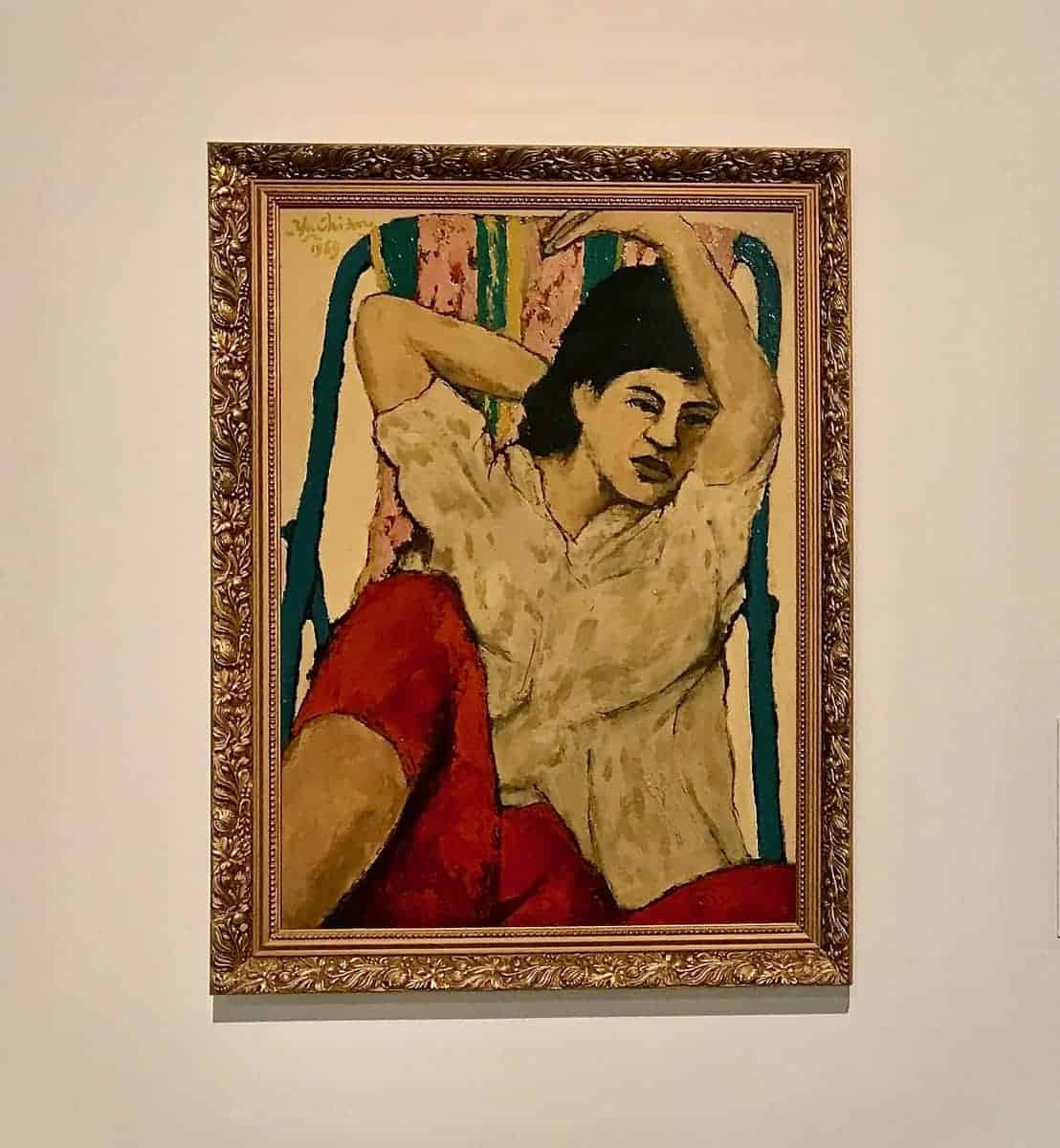

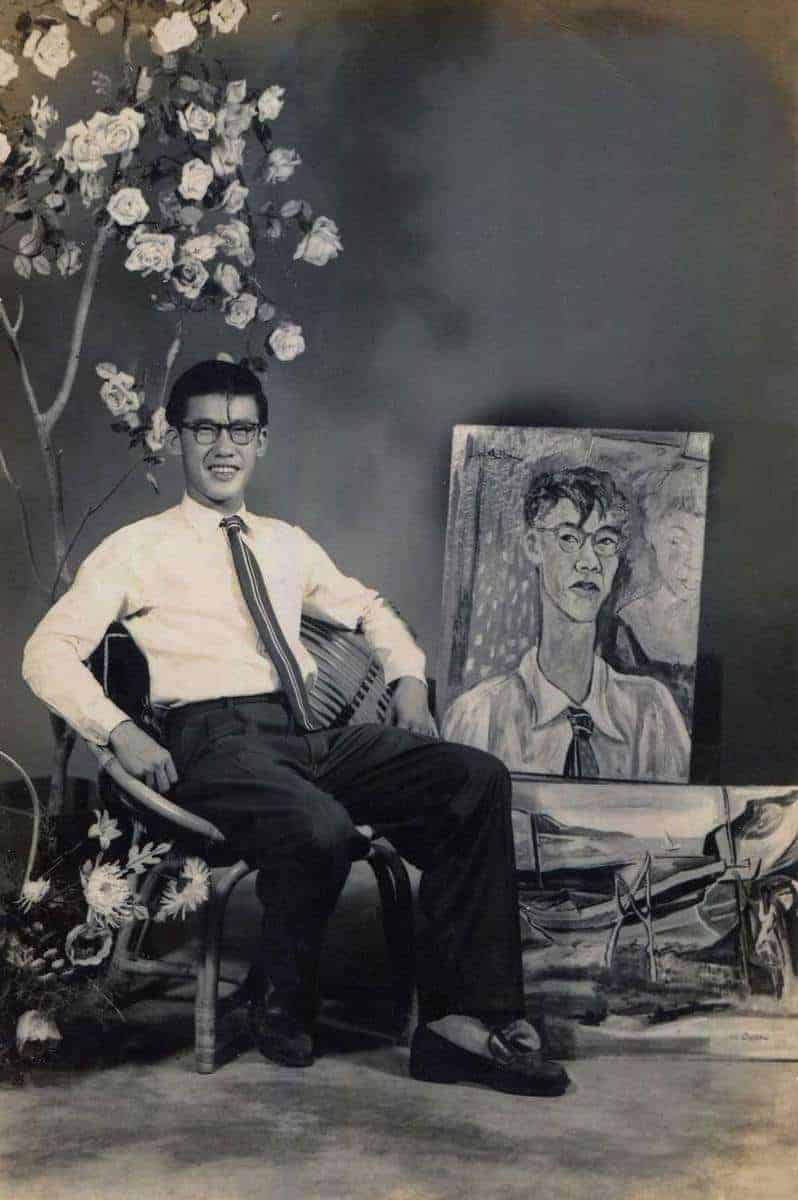

There’s an old photograph of artist Chia Yu Chian with a pipe in his mouth, his right arm extended and embracing his wife’s shoulders, both grinning, while a portrait of his wife seated on a lounger rests on the ground. This very portrait, Gadis Sedang Duduk, is the first painting that greets the audience in Chia Yu Chian: Private Lives, curated by Simon Soon and Rahel Joseph, and showing at Ilham Gallery in Kuala Lumpur until 23 June.

The portrait of his wife offers an intimate glimpse into Chia’s personal life and prompts us to speculate on the couple’s private life when the portrait was being painted. The eyes of the subject are half-closed lazily, as though she is beginning to drowse in her chair, but some degree of alertness remains. Perhaps she is listening to a story or conversing with Chia

Almost all of the paintings in Chia Yu Chian: Private Lives depict the people and scenes of Kuala Lumpur and the towns that dot the Malay peninsula. The painting of his wife stands apart as one of only a few that portray his private life so intimately and openly. Hence, the “private lives” in the exhibition title refers not so much to the lives of Chia and his family, but rather, to the lives of individuals scattered throughout Kuala Lumpur and other Malaysian towns of the late 60s to 80s, as keenly observed by Chia.

The catalogue that supplements the exhibition features essays by the curators as well as past writings on Chia’s works by art historians such as Redza Piyadasa and T.K. Sabapathy. In curators Rahel Joseph and Simon Soon’s respective essays, they refer to Chia as a flâneur, a term originally coined by poet Charles Baudelaire but later further developed by philosopher Walter Benjamin to describe someone who roams the streets of the city while observing other people and their surroundings. Chia Yu Chian: Private Lives demonstrates that Chia was as much a painter as he was a documentarian of his time, the subjects of his paintings ranging from notable landmarks, buildings, shops and restaurants where the inhabitants of the city congregated, to individuals and scenes he observed everywhere he went. Also exhibited are his paintings of criminals, paupers, domestic workers, factory workers, gamblers and their families at the casino in the hill resort of Genting Highlands.

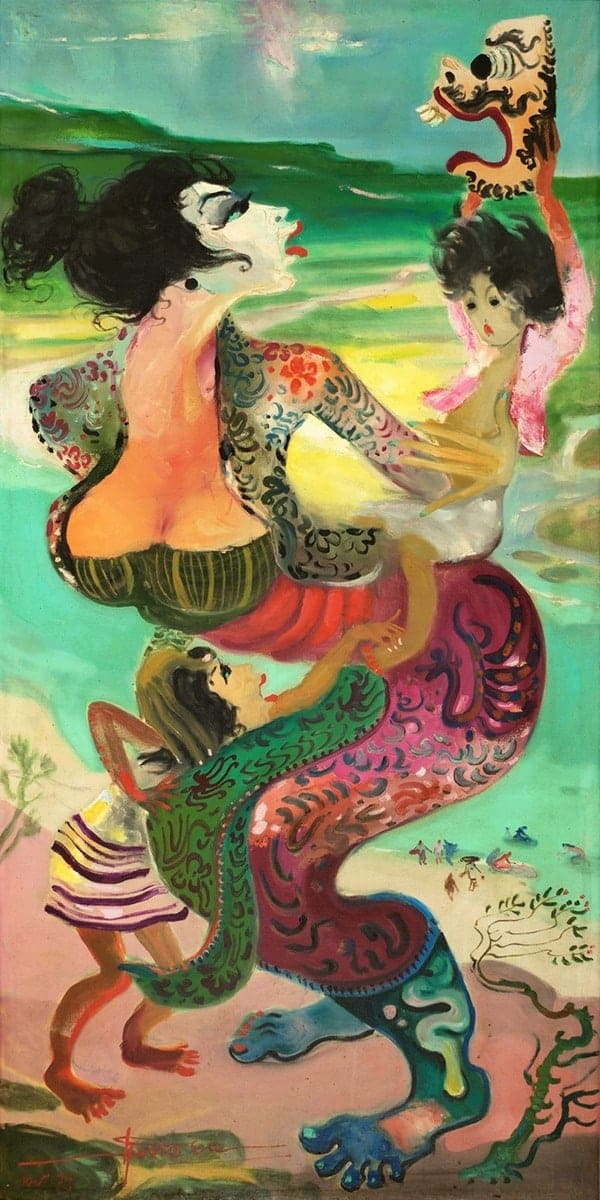

Chia studied at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1959 under a scholarship from the French government and was later informally mentored by eminent artist Chen Wen Hsi, a pioneer of the Nanyang Style. (The Nanyang Style refers to a particular genre of works by émigré Chinese artists working in pre-independence British Malaya, which portrayed local or Southeast Asian subject matter through a combination of Western styles of pictorial representation and Chinese ink and brush painting traditions.)

What unifies most of the paintings in the exhibition is their depiction of subjects, scenes and individuals on the margins of society, organised according to different themes. In one section, paintings that depict the sights that one would encounter during a stroll around the historic core of the city offer an inkling of what Chia himself saw as he wandered around the city from his apartment in Selangor Mansion, one of the earliest apartment buildings in the city. The paintings encapsulate a slice of time before skyscrapers dominated the skyline of Kuala Lumpur as we know it today. A documentary about Selangor Mansion by photographer and filmmaker Mahen Bala, commissioned for this exhibition and featuring residents of the building, complements the exhibition as they recount stories of lives and events that used to animate Chia’s apartment block and the area around it.

Accompanying the paintings are preliminary sketches depicting the same scenes in the paintings. By comparing the sketches (which make up some of the archival materials along with old photographs and press clippings) with the paintings, we see how Chia was able to inject an abundance of life and energy into what he observed. In a series of paintings depicting a period of his life when he spent considerable time in hospital due to various debilitating ailments, his signature wild brushstrokes and eclectic orchestration of colours turn the hospital, otherwise a grim setting, into a place brimming with life and vigour where the ill found comfort, solace and solidarity with each other. In Daily Work, we see female workers at the hospital carrying out their daily tasks. Even though sanitary masks cover their mouths, their eyes seem to suggest that they are smiling or laughing over stories they are sharing with each other.

The often unnoticed contribution of female labour to the development of the nation is made visible in Chia’s depiction of nurses, domestic helpers and other women workers in various paintings. In particular, the paintings that form the Ngan Yin Groundnuts Factory series shed light on a peanut processing factory from the 70s, whose workforce was made up of mostly women. In fact, a recently published book, The Merdeka Interviews, reveals that female workers made up more than 60% of construction labour in the post-Merdeka era of enthusiastic nation-building and fervent construction.

against the press clippings in the foreground. Image courtesy of Ilham Gallery.

Chia was very likely an artist with an activist streak like his contemporary Nirmala Dutt, whose photographic montages captured the underside of the meteoric construction and development of the city in the 70s that gave rise to affluent neighborhoods such as Damansara Heights and Bangsar. In Kenyataan 3 (Statement 3), Nirmala paired conscience-stirring statements with photographic images of dilapidated houses and socioeconomically disadvantaged children and families who lived along Damansara Road, to highlight the unequal distribution of wealth and development that was taking shape in the city.

Likewise, Chia observed and captured the scarring of the landscape through massive development activities in the 70s and 80s with works such as Reclamation, Work in Progress and Floods. In Work in Progress, only the excavator and trucks in the foreground are discernible while the topography of the scene appears to be enmeshed in a muddy ensemble of chaotic brushstrokes and colours. While he did not employ any explicit statement in his paintings, the works speak loudly and clearly about the underside of the country’s frantic and unfettered march towards economic progress and development then, which continues to this day.

Walking through the exhibition, I couldn’t help but wonder at how much Kuala Lumpur has changed since the 80s. Have the living conditions of ordinary people and the working class that Chia painted changed considerably for the better though? Chia Yu Chian: Private Lives serves as a powerful reminder that these individuals continue to live amongst us in the city, mostly unnoticed and their stories unheard.