The notion of identity may not be new as a theme in contemporary art, but a recent exhibition at the National Gallery of Indonesia in Jakarta revealed artistic excellence that drew particular attention to the issue.

Artists Bibiana Lee and Indah Arsyad came together in the exhibition Id: Sengkarut Identitas (or, Chaos Around Identity) to present works layered with biographical, traditional and historical notes, revealing pain and trauma hidden behind a façade of beauty.

Referring to the notion of identity as it is understood in Indonesia, both artists explored their respective histories. Bibiana Lee based her work on her personal experiences as a Chinese minority in Indonesia, while Indah Arsyad who was born to a Javanese father and an Ambonese mother, and who lives in urban Jakarta, explored the notion of disappearing elements of cultural identity in the face of globalization.

The ‘id’ in the title of the exhibition had particular resonance.

It has meaning in the Freudian sense, while also referring to ‘ID’ in the manner of official identification– national documents and formal methods of classification that feed into the power structures which shape our identities. As Prof Dr Melani Budianta emphasized in her introductory speech to the exhibition which ran from 19 May this year to 16 June, the artists subconsciously invited us to consider what, why and who we are.

They made us ponder our realities.

And what tools did they enlist in this endeavour?

Bibiana took to refined and fragile Peranakan porcelain while Indah found relevance in traditional shadow play, brought to life through the medium of photography.

Bibiana recounted that as an Indonesian Chinese she had to face stereotyping and discrimination throughout her life. However, when the popular Christian-Chinese Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (known as Ahok, or BTP) faced rampant racial attacks during a re-election bid (ultimately losing his seat and being thrown into jail), Bibiana became even more intensely aware of the fragile situation faced by the Indonesian Chinese.

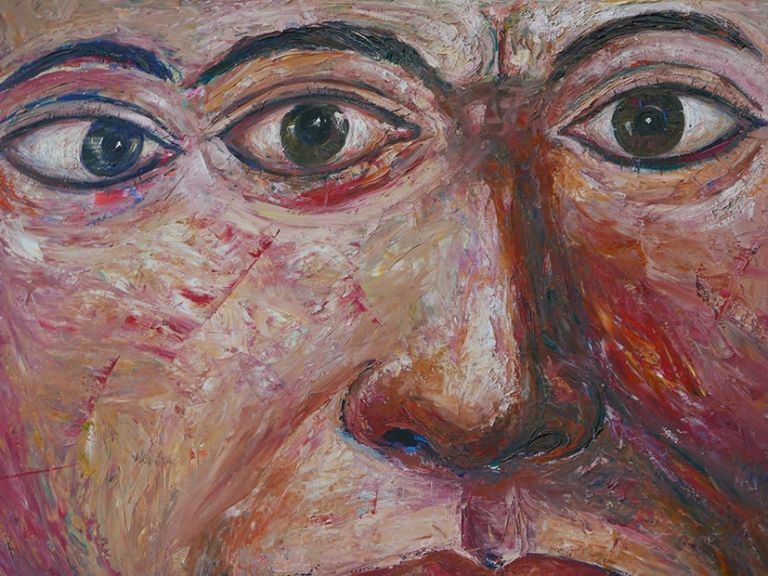

With these notions of fragility in mind, Bibiana displayed delicate ceramics painted in colourful hues. The artist felt that it was apt to use porcelain to represent the ‘new Peranakans,’ or the Chinese Indonesians who have never known mainland China but are only familiar with their current motherland, Indonesia.

No one would expect to find derogative or critical text beneath Bibiana’s beautifully decorated symbolic images such as those of phoenixes, peony flowers and tortoises which appeared in bright yellow, turquoise, green, blue, pink and red colours.

Imagine sipping aromatic tea from a beautiful flowery china cup without being aware that, integrated in the petals of the flowers on the cup, are derogatory words!

(But then, of course, such a teacup would be an artwork, and should be handled with care!)

Bibiana’s works were grouped thematically. While identity politics featured as an overall theme, the pieces addressed the entire spectrum of Indonesian history, from the events of 1998, to the New Order, Reformasi, and the gubernatorial election process of 2017.

In her saucer titled A Nation Divided: Bhineka Tunggal Ika, Bibiana applied a green colour in combination with yellow and red. She explained, “for this special piece I applied the green color that Muslims like to use, and yellow, the universal color to represent the Chinese.”

She added that the use of red spoke to the Chinese proclivity for such colour, while also being symbolic of anger and passion.

Another intriguing work referenced the May 1998 riots in Indonesia where the most horrific violence was inflicted upon its Chinese community, and especially its women. Bibiana explained that even till today, the human rights violations of that time have not yet been truly addressed.

The plate broken into pieces reflected a sense of heartbroken feelings. However, a ray of optimism shone through with the artist’s remarks that “it is only after this dark episode in history that the Chinese in Indonesia begin to stand for their rights and enter politics.”

For Indah, questions of identity arose when she thought about her parents and of how she is of mixed Ambonese and Javanese descent.

She explained, “I grew up in Jakarta where many cultures mix into a general urban culture. But it’s still vivid in my memory how my grandpa loved to watch the wayang shadow play.”

The memory of her grandfather prompted Indah to contemplate her own identity which is neither fully Ambonese nor Javanese, and the amalgamation of the two layers of her personality, creating a new sense of self – akin to the process of what happens during a butterfly’s metamorphosis.

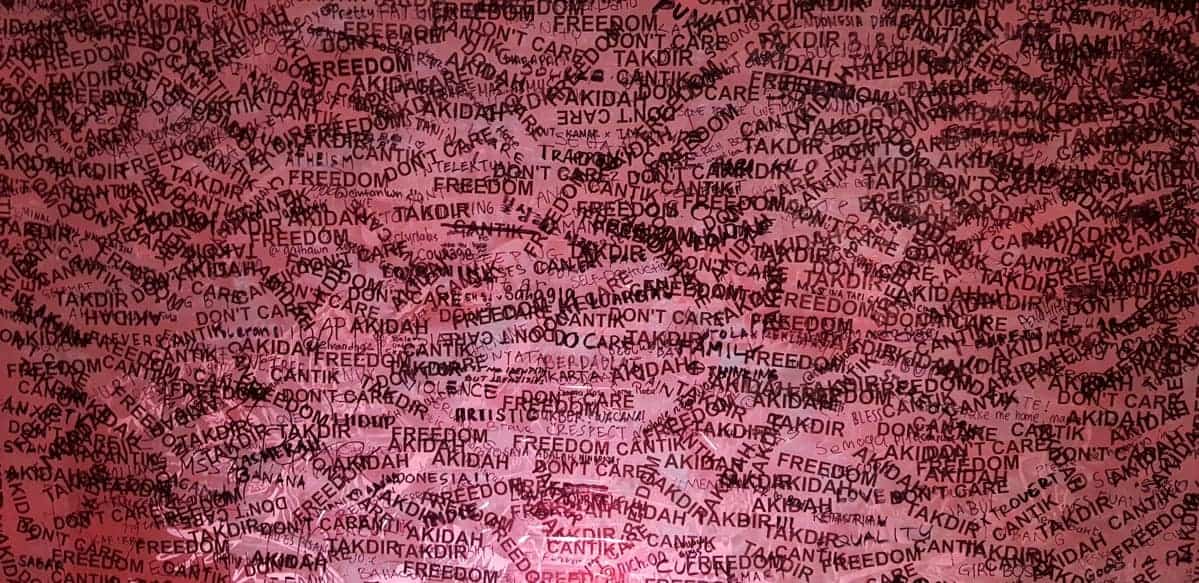

To bring that idea to life in her art works, she interviewed six people. Naming her project ‘Butterfly,’ her fascinating multimedia work began with the taking of photographs of her subjects – people from various social, religious and economic backgrounds. While speaking with them, she found that their identities had transformed over time, precipitated by changes in lifestyle, migration and cultural assimilation, amongst others.

The stories she collected were quotidian, yet multi-dimensional – from the rich woman who wanted to keep up with the crème de la crème of society, and accordingly moved away from home in order to have a face lift, to the simple housewife from the village, who moved to the city to earn a living and open a warung. A young student who moved to Jakarta as a small child with his parents, in pursuit of a better life and income, shared stories about how mixing with Betawi children (i.e. native inhabitants of the city of Jakarta) entirely erased his sense of origin, to the point that his own personal identity seemed irrelevant.

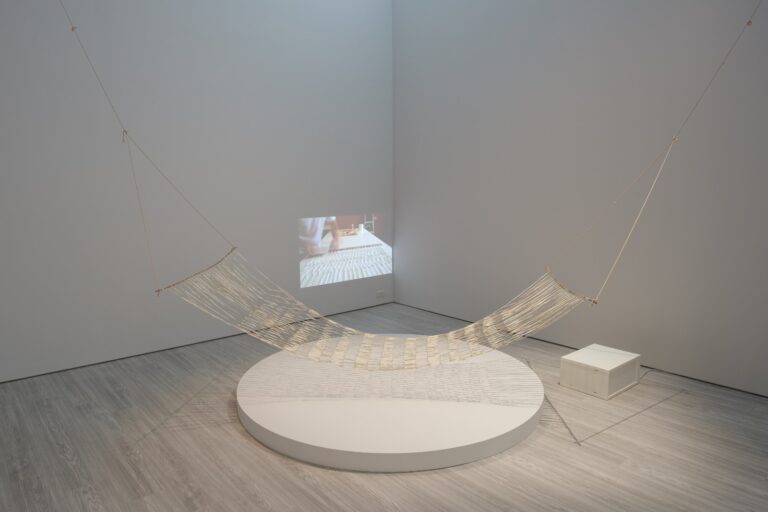

To embody these metamorphoses, Indah made photographs of the people she spoke with, at their respective locations. These photos were then mirror-printed onto transparent acrylic sheets. Indah subsequently added engravings of ancient mythological Javanese symbols to the acrylic. In the exhibition, she used flashlights and LED coloured floodlights to catch the engravings and project them as shadows on the wall.

The final effect was that the shadows of the engravings were propelled onto the same plane as the those of the blown-up photographs (i.e. the background wall of the exhibition).

While the images in shadow-form seemed flat and one-dimensional, the layers between the wall, photographed subjects and acrylic sheets communicated deep complexity

The result was this:

In one iteration of the work, visitors were also invited to become part of the art on display and to write their identity and socio-political problems faced, on stickers to be placed on the transparent acrylic. The final result was testimony to the impact of the different influences that are capable of overshadowing and overwhelming the human figure.

Both Bibiana Lee and Indah Arsyad worked with simple tools, but demonstrated a tenacity and attention to detail that mirrored the complexities of their artistic message. Bibiana explained that she took over a year to create her porcelain pieces as the process “required rigorous checking of each and every text … and colour.”

Indah, while utilizing humble equipment such as the flashlight, and pencil and paper (for the initial drawings of her mythical Javanese symbols), painstakingly photographed her subjects at each of the models’ respective locations.

With this presentation, both artists were able to show how art plays a liberating role in the face of human tragedy. As an expressive tool to bring important issues to the fore, the artists subtly but poignantly invited us to re-examine our understanding of the human essence, not just in the Indonesian socio-political sphere, but in life as a whole.