Zoe: We walked this morning. You and I. Two metres apart and ‘masked’. Knowing we were bending the rules for this ‘outing’. We are both solitary in temperament and living, despite this virus lock-down (and its demand for social-distancing), but I felt much more ‘normal’ as a consequence of actually being with someone in the flesh! After three weeks of talking to the plants in my apartment, I returned home with gratitude for our friendship. Such unprecedented times have me not only appreciating the people I can count on, but the habits that structure my time – like reading, cooking, writing, and playing music. And I am immensely relieved to have such interests at this moment where being alone in the face of an uncertain near future can be mentally exhausting. But I (we?) are also immensely privileged to have this time, to be spent in such a way. We can afford to be socially distant – we have a roof, access to food and medicine. But for how long? And it strikes me that since I moved to Vietnam, this question of ‘but for how long?’ has been in fact a continuous present. It is not as if what you (artist) and I (curator) do for a life is by any means ‘certain’ – the arts in Vietnam being the most stringently monitored, controlled and least supported area of human production. I wonder if this subjection to fragility and strategic survival makes for resilience in our local artistic community at this pandemic moment, and if in fact, this uncertainty as principle, is in fact our normal?

Lena: Even in uncertainties there are different levels, shades, magnitude and intensity. I don’t see artists as any more resilient than others. I agree that creatives are so privileged in that we entertain ourselves well and that our work fundamentally can still go on in some form. Work can continue but money might become a source of anxiety. At least I don’t have anyone that depends on me for a living. Looking at my entrepreneur friends I really feel the strain. Businesses they’d painstakingly spent years building can easily go down the drain. It is brutal. Currently, the situation in Vietnam is calm, not yet chaotic, enough to make us realize how fragile a relatively smooth-running norm is. But it is as if we are all holding our breath, wondering for how long we can keep things under control.

Zoe: But is uncertainty our normality in Vietnam? By ‘our’ I refer to the local artistic community in Vietnam initially, and my call out to my thinking of its resilience is really a reflection on surveillance in our creative midst (all artistic activity desired for public audiences must be approved by the State). Our readers here may not be aware that the surveillance engines of Vietnam are what we ironically have to thank for the stringent measures carried out in tracing this highly contagious disease (thus our infection rate has been relatively low). I must say I am heartened by the minimal craze of hoarding in Vietnam (unlike my home country’s embarrassing fight for loo paper for example); and I am also impressed by the collective citizen responsibility in ‘staying at home’ whilst also caring for the needy (local restaurant owners accepting donations of food in order to cook for the homeless, for the street vendors forbidden to work etc). I am always impressed by the sense of solidarity in facing calamity in Vietnam – its history of conflict long and recent – and perhaps that is also why Vietnam’s response to this pandemic has been so successfully measured? Dealing with uncertainty has been a constant?

Lena: Because we are still in the midst of it, I find it hard to make broad evaluations of the government or the people. The low numbers reported is an imprecise indicator of the threat we face. The government has, however, acted strictly early on, quickly closing down schools since late January and putting people deemed to be at risk in quarantine. Up until this point the state bears the entire cost of treating COVID 19 positive citizens, housing and feeding all quarantined individuals. But this is a long battle so I hope we don’t run out of steam. I actually think the surveillance engine of Vietnam is fairly outdated compared to some other countries like South Korea and Singapore where if you didn’t remember which taxi you got in, the authorities can quickly find out, via CCTV, your card transactions and phone logs.

I don’t consider art making an uncertainty. If a type of uncertainty becomes a form of normality then it’s no longer uncertain. Prior to COVID 19 there were always many elements that might go wrong: ideas not working out, delayed production or shipment, shows not being given a permit, money not coming through, etc. But invariably, some planning is possible. For artists, works that are not given permission to show in Vietnam can still be made and shown elsewhere or online, there’s no-one preventing us from making what we want in our private studios. A space faces many more constraints as you have to work more closely with the authorities. All the same, you can still schedule programs and shows a year in advance. Our community is very small and that allows certain spontaneity and flexibility. The uncertainties right now, however, make planning with each other very difficult. We don’t know exactly when the lockdown will end. We don’t know when and where we can travel to. Is it 1 month, 3 months, half a year? For independent gallery spaces, there is the pressing question of whether they can last that long…

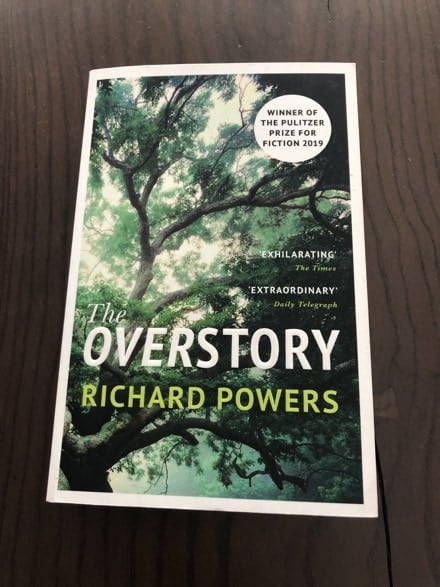

Zoe: Yes you are right that uncertainty is no longer being ‘uncertain’, if it becomes normalised … i hadn’t thought of it that way! I’ve just finished reading The Overstory, by Richard Powers, a stunningly crafted piece of (Pulitzer winning) fiction about the presence of trees in our world, of their memory, their physical reflection of time, of the necessary decay, of how differing species are with language that care for each other. Powers states ‘You can’t see what you don’t understand. But what you think you already understand, you’ll fail to notice’. It’s a quote that has stuck with me, considering our changing habits of ‘normality’ will unlikely be what it was. We can’t see this virus and so our interactions are now with liability, which makes for considerable paranoia for we likely will fail to notice its spread. This book, read over the anxiety of the past month, has me noticing my dependency on ideas and knowing what affects my mood. I’m compelled by artistic premonition – such as Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s Empty Forest film (2017), where the extinct white rhino says ‘… then i will reincarnate as a deadly virus to infect all of humanity’ (!); i’m re-reading phenomenology and how the role of perception needs to be better studied and released in order to re-acquaint the human and non-human lifeworlds; I’m re-membering previous ‘homes’ and recalling the music that once buoyed my space and thus are obsessively played (Stereolab and Yo La Tango are currently filling my ears). But I’m worried for my team at The Factory and our current seemingly endless ‘leave without pay’ – when and will we be able to re-open? I’m listening to the news every night and trying not to feel guilty for my privileged cocoon. I’m prompted to ask what can Art be at a time like this? How can I / we contribute to the remembering of this moment?

Lena: Cooped up inside, I imagine the Arts is providing solace to many of us. I cannot count the number of times it has saved me from loneliness, or worse, crippling emptiness – another silent invisible force maybe even more deadly than viruses. As an audience, I’ve been able to read more, watch more, and contemplate somewhat. Last week I finally read Albert Camus’s The Plague. With a prose clear, crisp, and devoid of overt sentimentalism, Camus reflected on human life and the struggle against death and evil in the shape of an outbreak in a major coastal city in Algeria. Set in the 40s, it’s still very relatable and relevant. I also coincidentally came upon Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind yesterday and was struck by the opening scene of a barren landscape where a man and his ostrich-like steeds don heavy-duty masks as they walk through a village engulfed in toxic spores. All is dead except for insects. These themes of death and decay, human relationships with each other and the environment have come up again and again in many forms and narratives. We do not lack the imagination to foresee future disasters, nor do we lack experiences of past disasters to learn from, but often we resort to hoping that whatever looming problems will go away by themselves. I’m curious about how the world will change. Will we become more isolated and individualistic as more things shift online, and touch becomes taboo? Will we come to value the blue skies and clean air the lockdown has induced? Or will we simply revert back to much of what we were used to?