For Plural’s upcoming online shop, artist Justin Lin collaborates with his partner, metalsmith Jenny Lin of the tiny torch to create a limited series of handcrafted jewellery pieces based on his artwork. Our Editor Michelle explores what it takes to create a piece of metal jewellery through a workshop with Jenny herself.

“Try to make sure you saw up and down the full length of the blade,” metalsmith Jenny Lin instructs me about using the jeweller’s band saw, “You want to put enough forward pressure on it so that it catches the metal, but not so much that you see a bend in the blade.”

“It has to be a good balance between control and letting it do what it needs to do.”

Perspiration beads my forehead as I begin to wonder if I’ve bitten more than I can chew committing to this workshop. The notion of control and balance seem like complete strangers to me after the previous night’s binge of potato chips – but today’s a new day, right?

I am in Jenny and Justin Lin’s home studio, a cosy metalworking space that occupies one room of the couple’s HDB apartment. I am here to learn how to create a piece of jewelry using the sawing technique, which is one of a jeweller’s most basic and essential skills.

Much like how one draws by pulling a pencil across paper, sawing through metal is done by working a band saw up and down through the sheet of metal. Its line of tiny teeth bite through the metal, cutting a journey through the sheet.

I practice cutting lines in the sheet of scrap metal that I’d been given – first straight lines, and then turning curves. Though the process takes a fair amount of elbow grease, I’m relieved that it is not as daunting as I had feared.

Before long, I’m ready to start on sawing a piece of my own design. I look around the studio for design inspiration, and chance upon a sketch that Jenny had made based on one of Justin’s works.

The abstracted wavy lines of the marker sketch mirror the bent brass lines in Justin’s original work. Though minimalist, these forms are somehow highly evocative: they resemble both mountainous and riverine landscapes, and invite one to contemplate nature.

Justin shares that this series, entitled Fields, is inspired by the vistas that he once encountered. Through his art practice, he aims to uncover the interactions that we have with our environment – the memory of landscapes once visited, and the stories that we write when we inhabit a space. Etched into metal, these scenes memorialise a moment in considered, undulating lines that turn memory into object.

I decide to take a leaf out of his book and draw on my memories of Ryōan-ji, the famed Zen temple in Kyoto that I ache to revisit. I choose Ryōan-ji for its serenity and stillness, eager to use this opportunity to revisit a place – at least in my mind, since I cannot do so in real life.

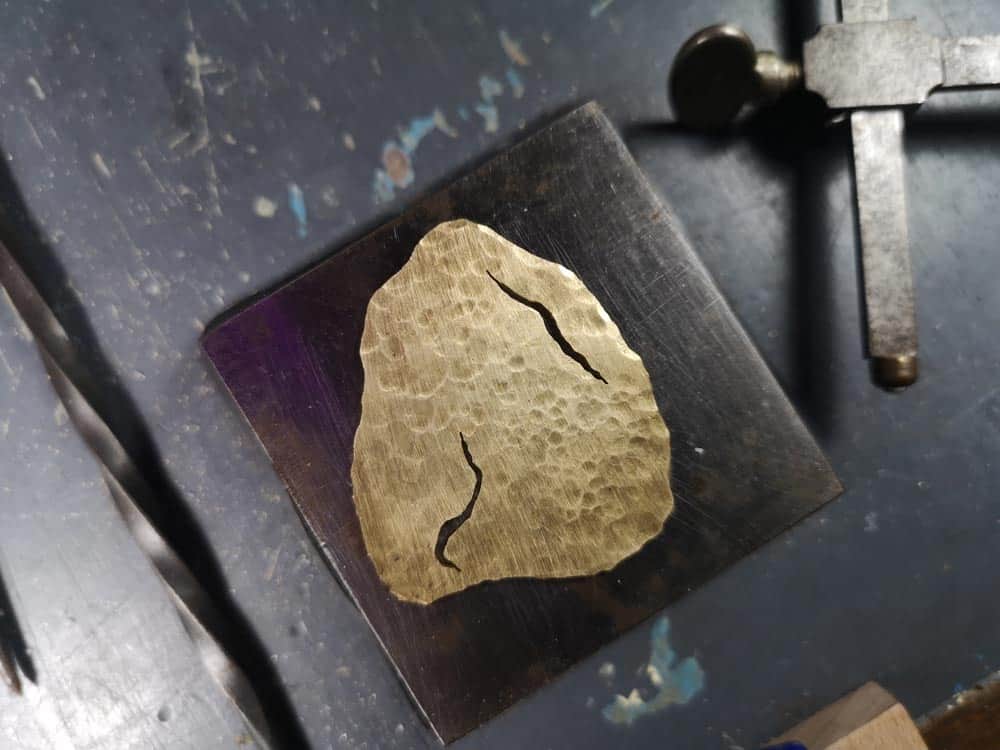

I sketch out the loose lines of a rock based roughly on the rock forms in the Zen garden. When that is done, we adhere the sketch to a piece of metal so that it guides my sawing. Then it’s back to the bench pin for some hardcore sawing, before finishing what I’m calling Arm Day on my calendar by wielding various hammers to texture the surface of the brass.

As we work, I chat with Jenny about the challenges of metalsmithing, especially in Singapore. To Jenny, one big challenge is the consumer’s mindset that jewellery does not require maintenance. She says:

“Most people don’t understand that the only metal that won’t tarnish, ever, is solid gold jewellery. Everything else will tarnish, because all metals react to the environment; all metal oxidises. It’s a reactive material, especially in humid Singapore.

I wish people had more love for maintaining things. I think good quality jewellery is about accepting and enjoying the fact that you get to spend time taking care of the piece. It is part of the relationship that you have with it.”

She shares that the key to having long-lasting jewellery is to choose pieces that are made of solid metals of known origins. Knowing what the metal is all the way through means that when it tarnishes – as things do – one can easily replenish its shine with a simple polishing cloth. This is not the case for the rhodium-plated jewellery that saturates the fast-fashion market, where the plated surface often hides a questionable alloy beneath that the jewellery industry calls ‘pot metal’.

“Pot metal is made by literally taking leftovers from everything and dumping it into a pot. There’s been scares where they’ve found amounts of lead or magnesium or other toxic things in pot metal. It’s harmful to your skin, which is why they rhodium dip it,” Jenny explains.

When the coating of plated jewellery wears off, they need to be replated. It is a resource-intensive process that uses a lot of chemicals, and more often than not, people throw out their jewellery when they wear out their shine.

I look down at the little half-formed piece of metal that I’ve just spent an hour creating, vowing never to throw it out. But of course what I have is still an unfinished object. Now that the design is sawn and hammered into shape, it’s time to solder the pin backs to the pin.

Jenny first demonstrates how she does so with a tiny jeweller’s torch, some wicked hand-eye coordination, and a little bead of molten silver. To my eye, the process resembles magic, or surgery. Those who had the fortune of taking metalwork classes in their schooling years might be able to articulate more clearly about how capillary action draws the piece of silver solder into the grooves where it hardens and binds the pin to the pin back. I’ll settle for not setting the room on fire.

Even with the help of the expert, it took me several tries before we got my pin back attached to the pin. Then it’s off for a dip in what jewellers call the pickle pot, an acidic liquid designed to clean metals of the oxidation and flux that they accumulate over the course of the soldering process. A hot bath and several rounds of polishing with various tools later, my rock is finally a fully-functioning piece of wearable jewellery.

As I walk out their home studio donning my new brooch on my chest, I’m struck with a newfound appreciation for what it takes to create handcrafted objects such as this. They are not even palm-sized, yet their size belies the dedication and skill that goes into their creation. It’s a journey of sweat, fire, and chemistry – as is the case with the relationships that we cherish the most. It’s no wonder that they take effort to maintain, but it’s also no wonder that they deserve that effort.

______________________________

Note: Inspired to own something handcrafted by Justin and Jenny? A limited selection of their jewellery pieces are exclusively available at Plural’s online shop, Shop Plural!