I’ve always struggled with the term ‘curator’, even as I’ve engaged in projects where I’ve taken on multiple duties that seem to make up the job scope of a curator. Perhaps it’s the institutional trappings of the word, or the hazy and evolving definitions of curating. As I define my own curatorial practice, I find myself simultaneously acknowledging traditional roles of curators and attempting to move beyond it.

What do curators do, and what are the expectations that come with taking on the role of a curator?

Is it about making exhibitions and writing texts?

Is it about researching artworks and artefacts, histories and geographical contexts?

Is it about organising programmes for the public?

Is it about creating spaces for certain narratives, stories and conversations to take place?

At the core of it, the meaning of the latin word ‘cura’ is that of care – in Ancient Rome, curatores took care of public works (aqueducts, bathhouses, sewers), and in Medieval times, a curatus was a priest devoted to the care of eternal souls. By the end of the 20th century, the occupation of a curator began to take shape as a keeper of a cultural heritage institution. It is a definition that persists up until today. Yet, what does it mean to curate in, and for, the 21st century?

This is one of the topics of ‘MRadio, a new podcast series by the National Heritage Board-organised Museum Roundtable which comprises over 50 public and private museums and heritage galleries in Singapore. I had the privilege of sitting in during the recording of Episode 2 of this podcast, which took the form of a conversation between Nalina Gopal, curator at Indian Heritage Centre, and Seng Yu Jin, senior curator at National Gallery Singapore.

For the uninitiated, the Museum Roundtable has been organising museum-related talks and sharings over the past 5 years. These programmes cover a variety of topics relating to working in museums – from museum education to exhibition design, to conservation and collections management. With the spurring of the pandemic, the push to reconsider accessibility and relevance in content production seems to have catalysed this podcast series to the benefit of museum-loving audiences. Incidentally, the accessibility issue was also at the forefront of the engaging discussion on the topic “On Art Meets Social: Curating for the 21st Century”.

To those outside of this field, the curator’s role in a museum may be shrouded in mystery, and the term ‘curating’ may be vague or confusing. In fact, this issue kickstarted the discussion.

Today, the word ‘curate’ is increasingly being used in broader everyday lifestyle contexts such as the curation of food menus, music playlists, and even exercise plans. There seems to have been a shift in patterns of consumption in recent years where, instead of producing cultural artefacts, companies prefer to select or curate them instead. As such, these brands accumulate cultural capital by making themselves appear as arbiters of taste and style.

In her response to this provocation, Nalina raised the point that, to some extent, this does make up a part of a curator’s role. Curators act on their museums’ behalf to decide which artworks to collect and exhibit, and in doing so, shape the lens through which visitors experience the museum. However, as Yu Jin pointed out, what is lacking in the uses of the word ‘curate’ is the importance of research in distinguishing a museum curator’s role. He says:

“…Research is really the engine that drives the museum, is really what forms the knowledge base of a museum and for curators, and it’s only through research where curators do their field trips and in my case, interview artists, acquire information [and] knowledge, develop collections, that we start to think about what curating is, and what curating does. It’s only from the position of research whereby we are able to inform the whole process of selection, the processes of deciding on display, of developing curatorial frameworks, [and] of creating identities for not just our exhibitions but also for our museums.”

The ensuing dialogue drew out key points that both curators felt strongly about. Personally, I agree with them both. My experience working at a research centre of contemporary art has shown me how research is an important foundation upon which meaningful and well-developed exhibitions are built.

At the same time, I think the word ‘research’ is itself a multifaceted being. In a conventional understanding of scientific research, one undergoes a systematic investigation of theories through experiments, peer-reviewed papers and so on to prove a certain hypothesis. However, research in the arts is less concerned with seeking out a correct answer, and more interested in exploring the issues and contexts that surround an idea to build up new knowledge.

I’m personally most interested in artistic research, also seen as ‘practice-based research’. Broadly speaking, artistic research is conducted with artistic practice both as its method and as the object of research itself. It focuses on “the movement in concepts, understandings, methodologies, material practice, affect and sensorial experience that arises in and through art and the artwork”. In taking on this approach, artistic research argues for new knowledge, or rather new ways of knowing.

As a young curator who also has an artistic practice, I see my work as merging both forms of research. It combines the knowledge of artists’ practices and contexts with experimental approaches that bring to the forefront theoretical concepts and embodied experiences that emerge from the encounter with the artwork. For example, in my recent exhibition immaterial bodies (as part of Objectifs Curator Open Call 2020), it wasn’t just about building the knowledge on the artists’ practices and works; it was also doing extensive research on affect and the body, and creating an exhibition that could allow such experiences to take place.

In putting together the exhibition, I found myself engaged in the same processes as when I make artworks – I follow the materials by becoming attuned to them and allowing the work to be responsive to where the ideas, conversations and research take me.

From Nalina and Yu Jin’s perspective, the significance of research takes on a slightly different function. After all, they both work in institutions invested in the regional and historical narratives that are the sources of the museums’ objects and artworks. Throughout the podcast, they discuss and reveal various aspects of their work that perhaps are not immediately evident: the curator’s responsibilities in representation, self-reflexivity and acknowledging loss; accessibility to their audiences; and telling stories that preserve the narratives of the plural and diverse communities they serve.

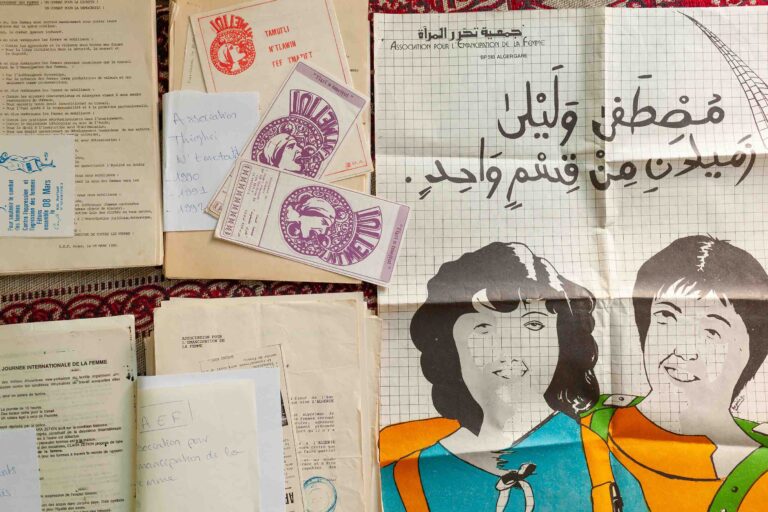

For the Indian Heritage Centre, as a community-centred museum that is focused on telling stories of the diasporic Indian community in Singapore and the region, Nalina shared how they have a curatorial responsibility to consult people on the stories behind the objects in the collection and tap onto narratives that might entirely live within the collective memory of the community. As such, oral histories take on as much importance as physical artefacts in providing the context of how an object’s use might have changed over time and, significantly, acknowledging loss or gaps in the collective memory.

For the National Gallery, with the largest public collection of Singaporean and Southeast Asian art, Yu Jin articulated that museums and exhibitions are not neutral, and hence curators have a responsibility to be self-reflexive in their methodology of making exhibitions. One such exhibition at National Gallery Singapore was Re(collect): the making of our art collection, which tackled the making of the National Gallery collection since the 1960s and how it continues to evolve today. In the course of preparing for this exhibition, the curators turned the gaze back on themselves, researching extensively on the types of acquisitions in the museum’s collection.

Significantly, what this revealed was that female artists were vastly underrepresented in the collection, a finding that was intentionally reflected in the exhibition Re(collect) in order to begin to unravel the institutional structures that have systemically discriminated against female artists, and prompt the curators to continue to work towards addressing this gender imbalance through future collection development and research. More than ever, curators today have a responsibility to continuously challenge structures that perpetuate discrimination and marginalisation, to give space to underrepresented and peripheral narratives, and they should be held accountable for continuing to do the necessary work that extends beyond curatorial gestures.

Of course, we are still in the midst of a raging global pandemic, so one unavoidable topic in the discussion was how the pandemic has affected exhibition-making and museums, and how we might develop sustainable practices in the future. It’s an issue that both curators do not shy away from. They both reassert the continued relevance of looking to the past in order to re-examine and reorient in contemporary times.

My biggest takeaway from this discussion on sustainability in the pandemic was a point that Nalina raised about how sustainability needs to be built into our practices of research and exhibition-making. Not only should we have good digital repositories and resources that increase remote access, we should also make sustainability a key consideration in how exhibitions are curated. Content could, for instance, be deployed across diverse platforms and extend beyond physical space. She says:

“When you have content that [can] transform platforms, it’s also important that the content is written acknowledging and addressing the fact that there could be audiences who could be from anywhere and any kind of background… And I think this is a huge challenge. I don’t think any of us can safely say that we’ve mastered it. I think it’s a learning space, but it’s important for us to acknowledge that our audiences are changing very quickly. Especially perhaps during this pandemic, a lot of us have realised that our information is being consumed by parties that might not be our traditional target audience.”

Nalina goes on to bring up another important point: that it’s not just about going fully digital. The digital elements of the exhibition are useful in feeding research and enquiry, but curators must also observe what can be withheld from the digital space in order to retain a physical exhibition experience that audiences will still return to the museum for.

This is something that I have also been thinking about considerably in my curation of immaterial bodies, where the digital platform that we developed was a supplement rather than a substitute of the physical exhibition. At the same time, it offered a range of materials from artistic entanglements to commissioned writing responses and video introductions that sought to complement and not compete with the exhibition.

Yet, even as curators are in the midst of these processes of discovery, change and adaptation in the way they work, the question of “how do we curate in the 21st century?” that the podcast attempts to tackle remains an open one, and one that will continue to evolve. I would highly recommend listening to the full podcast for the nuanced accounts and insightful perspectives that the curators surface as they chart future directions on curating. And perhaps, it would also surface reflection on how at the end of the day, even in the 21st century, curators continue to “care for” – perhaps not for aqueducts or eternal souls, but with equal dedication for objects, stories, and people.

______________________________

This second episode of ‘MRadio, “Art Meets Social: Curating for the 21st Century: A Conversation with Nalina Gopal and Seng Yu Jin”, can be listened to here.

This article is produced in paid partnership with the National Heritage Board. Thank you for supporting the institutions that support Plural.