If there are winners in the Singapore art scene during the great pandemic of 2020/2021 – and that’s a big if – it’s the millennial artist.

It began innocently enough: National Gallery Singapore was supposed to bring in a show of Picasso and Matisse paintings in 2020. But border shutdowns and logistical disruptions made it impossible to transport the works over, not to mention the financial disaster of opening an expensive show in a year with virtually no tourists. So the Gallery looked to home instead and settled on two showcases of mostly young Singapore-based artists.

Suddenly, millennial artists such Priyageetha Dia, Ashley Yeo, Stephanie J Burt and Khairullah Rahim – all of whom, I should add, are very talented and deserving of space in any museum – were showing in the august halls of the Gallery, which since its inception has preferred blue-chip artists and historical works. Though the two showcases were uneven, they brought to my attention a number of other promising millennials whose works had never been shown in commercial galleries.

And then came the millennial tsunami at Singapore Art Week (SAW), which is happening right now across the island. Once again, arts organisations had to look inwards and not rely on regional or international artists who could not travel. And so, by default and design, SAW ended up giving young artists a platform many times larger than they ever got in its past eight editions – and the results are thrilling.

SAW is organised by the National Arts Council (NAC), Singapore Tourism Board and Singapore Economic Development Board. NAC’s new-ish Director of Sector Development (Visual Arts) is Tay Tong, who took on the position after 29 years as the Managing Director of TheatreWorks, a company that’s no stranger to groundbreaking innovations, with its iconoclastic Artistic Director Ong Keng Sen.

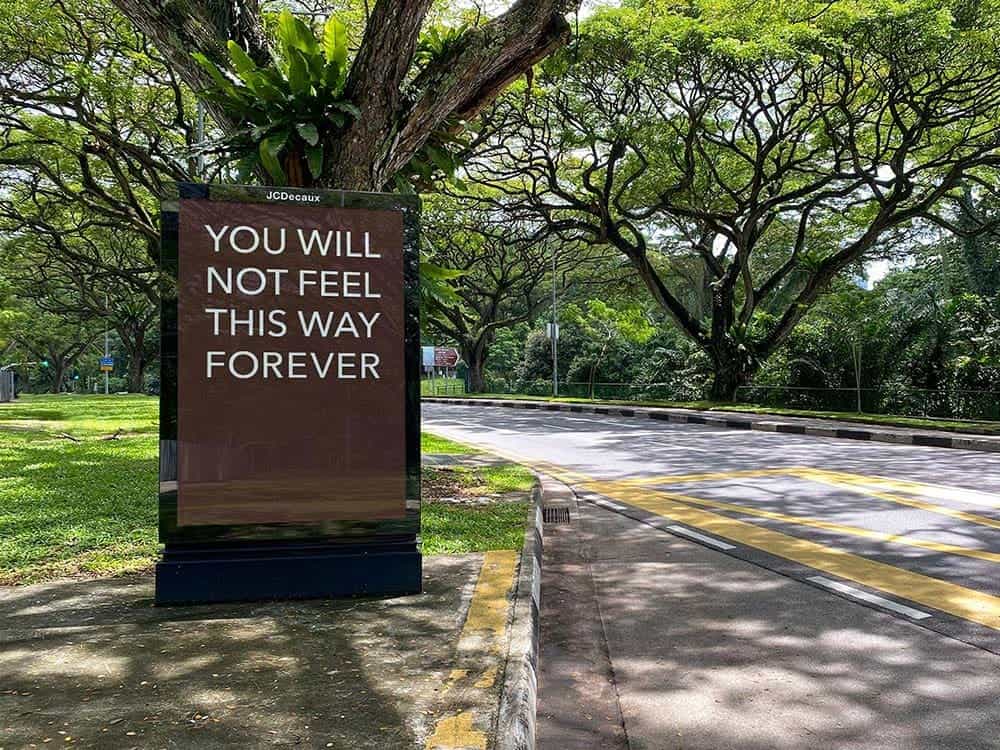

Perhaps influenced by TheatreWorks’ experimental strategies, Mr Tay and his team have taken risks in ways I have never seen in previous editions. They greenlit projects showing art at bus stops, on concrete pavements, in an ice-cream parlour, and other unlikely spaces.

But more than anything, the NAC team let loose a whole bunch of millennials running their own shows, never batting an eyelid that quite a few of them have somewhat next-to-no experience doing so – which, I should add, isn’t necessarily a bad thing. At a few shows, some millennials appeared to be still figuring out day-by-day how to actually mount a show, and how to manage the large crowds and queues. And while all this is great training ground for the future scene, they’ve also bulldozed through expectations of what a show should look like.

Millennials, I’ve discovered, hate paper. At most art shows I’ve visited around the world, there would be sheets of paper handed out to visitors containing a map of the room, artist bios, and other information to help me navigate the show. But millennials clearly don’t care about how it’s “supposed to be done”. At least three millennial shows at SAW had no handouts when I visited them. The conversation I had with the gallery sitters typically went like this:

“Hi, do you have any catalogue or printout I could take?”

“No.”

“Then how do I find out about the artists?”

“You can go to our website. All the information’s online.”

“Where’s your website?”

“Just Google it.”

“Right.”

“We have to save trees and reduce pollution.”

“Of course… I just like those paper handouts, you know? I can circle and underline things I like, and take them home.”

“You can take photos of the wall texts, and then draw circles on your phone.”

“Of course… sorry I asked.”

I didn’t like their sarcasm, but they were right, of course. We all need to use less paper – especially me who writes for a daily newspaper. Meanwhile at another show I went to (which had already been open for four days), the people running it didn’t know what to call themselves when I wanted to interview them:

“So you girls curated the show?”

“Not really.”

“Who curated it?”

“There’s no curator.”

“Oh? Who selected the works?”

“We did.”

“What do you call yourselves?”

“Hmm… that’s a good question… well, we organised it…. So maybe you can call us ‘organisers’?”

“Is that the right term?”

“Okay, how about ‘producers’? We ‘produced’ it – so, ‘producers’. Yeah, just call us ‘producers’.”

“Are you sure?”

“Well, we kind of curated it, but we don’t want to be called ‘curators’. It just wouldn’t be right.”

That made me smile. If there’s anything we need more of in the art world, it’s less pretension, more honesty.

A couple of shows at SAW had to close temporarily because of technical issues: a TV had busted, an electric circuit had blown, an installation hadn’t worked the way it was supposed to. Technical hiccups happen in the art world all the time. But in previous SAW editions, most of the shows were by seasoned gallerists and curators who knew exactly how to resolve it – and quickly.

Having covered all nine editions of SAW, none of the screw-ups I witnessed in this one was “business as usual”. But it didn’t matter because some of these millennial shows brought out some of the freshest, zestiest, zaniest, strangest, chicest, silliest, sincerest artworks I had ever seen in SAW.

While some millennial curators betrayed their inexperience, other millennials displayed preternatural skill and panache, as if they were born for the job. I have only caught 37 shows out of the 100-plus shows at SAW. But here are the some of my favourite ones featuring young curators/organisers/producers and artists:

One of my top three favourite group shows in all of SAW is The Orchid; The Wasp, at Blk 47 in Gillman Barracks. Organised/curated by Zulkhairi Zulkiflee and Racy Lim, it features some beautiful works by artists such as Ivan David Ng, Leroy Sofyan, Liana Yang and Thesupersystem, all in dialogue with one other artist on the theme of “becoming”. The genius of its layout is that every work connects incorporeally to the works closest to it, augmenting and expanding their meaning, such that you found yourself moving around the room in circles, not wanting to leave.

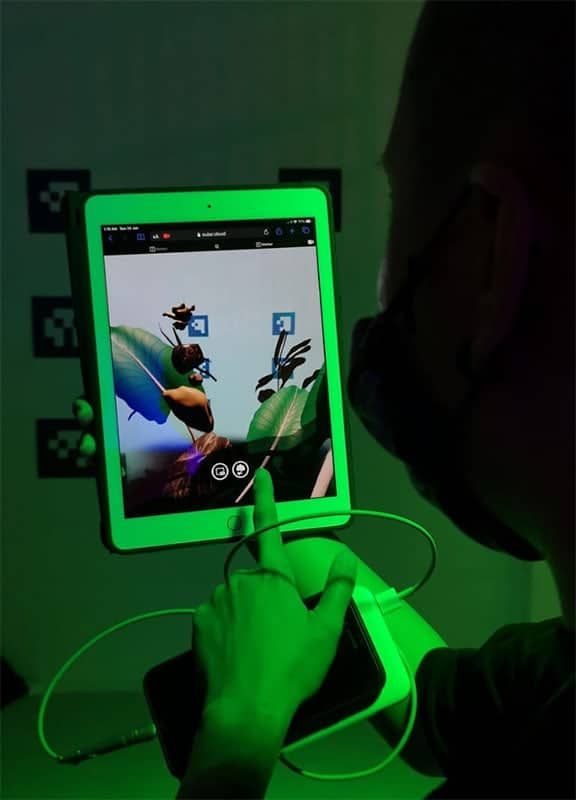

One of the most ambitious shows I’ve seen is Inner Like The OutAR by Mama Magnet at Blk 22 in Gillman Barracks. Curated by the impressively articulate Tulika Ahuja, it is a room-size art installation using augmented reality to create an immersive psychotropic experience. I can’t recall any other SAW show that has used AR as extensively as this show. To think that the 20-something Tulika runs Mama Magnet from her home, with only one intern who happens to be her neighbour.

Two of my favourite solo shows are Ian Tee and Nicholas Ong, both shown by Yavuz Gallery at Blk 5 and Blk 9 respectively, at Gillman Barracks. They trade in the visual language of young people (video games, IG filters, comic books, art cinema aesthetics) but their visual bombast masks serious critique of contemporary society. I admit I have a soft spot for Singapore artists who engage in social and political issues – we don’t have enough of them.

One of the longest queues I saw on the two days I was at Gillman Barracks was Shifting Between by Our Softest Hour (made up of Nature Shankar and Kimberly Kiong). One reason for the long queue is that each work requests some form of participation from the visitor. Divaagar’s parody of the wellness industry demands that you sit and submit yourself to a wellness video. Meanwhile, nor initiates lengthy chats with strangers, then gets them to write candid letters and paste them on the walls – you should see some of their raw confessions.

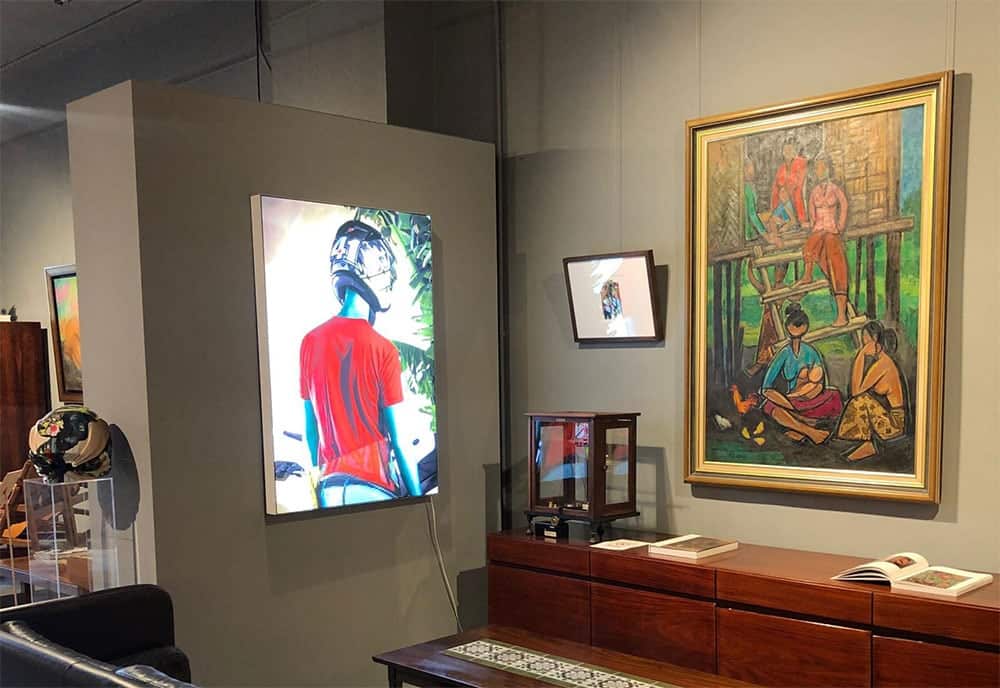

One of the youngest curators at SAW is 24-year-old Vivyan Yeo who’s showing The Body As A Dream at Art Agenda, S.E.A, at Tan Boon Liat Building. Art Agenda has a reputation among art collectors as a place to go find that rare painting by a Nanyang artist or Southeast Asian master. But the gallery has given Vivyan full licence to curate what she liked – so she’s picked works by iconoclastic young artists to display next to heavyweights such as Cheong Soo Pieng and Liu Kang. There’s a dreamy homoerotic photo series of shirtless boys by fashion photographer Lenne Chai. And there’s a beautiful lightbox of a mat motor (a Malay boy who rides motorbikes) by Zulkhairi Zulkiflee that parodies Cheong’s famous 1953 painting Malay Boy with Bird. If the Nanyang artists were alive, they’d have a lot to say about this.

And then there’s Maybe we read too much into things by curator Berny Tan and six artists (all of whom are no older than 31) showing at 72-13 Mohamed Sultan Road. Examining the materialities of commonplace objects, the show feels as soft and light as a daydream, with a penchant for serendipity and fleeting moments, temporary attachments and lost innocence — all cotton candy for younger millennials.

In the previous eight editions, SAW had tended towards the tried and tested, picking organisations, galleries and artists that already had a long resume and a reputation for doing these things well – understandably so. There were some smaller players, of course. But it was the marquee events (Art Stage, SEA Focus, IMPART Collectors’ Show) that attracted the audience, in particular the private and institutional collectors, the second most important people in the art ecology after the artists themselves.

In contrast, SAW 2021 had more of a “let’s give this a shot and see where it lands” attitude, which opened doors to so many young artists as never before. This was a big win for millennial artists – but it was also a big win for the millennial audiences, who instinctively understood the language these artists were speaking in and were ready to get on board. They were climbing under a small table to see a set of artist instructions, writing love letters to ex-lovers, diving into augmented-reality rabbit holes, and eating funny-tasting ice-cream in Funan with funny names like Moonlight Prata-ta and Misty Morning At Clementi Forest. I hope they become art collectors someday and help sustain the practices of the artists they love today.

When the pandemic eventually lifts, I also hope that SAW, the National Gallery Singapore, the NAC, and every cultural gatekeeper in Singapore, will continue to bet big on young artists – as they did this year. This year’s SAW was its liveliest edition yet, and the participation of millennial artists in droves for the first time had everything to do with it.

Incidentally, the unexpected positive consequence of the pandemic for millennial artists goes beyond the visual arts sector. Wild Rice had to ditch its 2020 theatre season, so it brought forward its residency programme for young directors who mounted new shows in record time. And while the country was still in Phase Two, Checkpoint Theatre surprised everyone by expanding its associate artist team from six to twelve, most of whom are millennials, and then broadening its work scope to include audio experiences, digital concerts, and a comic book.

But these are stories for another day.

______________________

The Singapore Art Week is now on till 31 Jan 2021. For more information, visit artweek.sg.

Feature image: Divaagar’s Alive Stream 2.0, an installation that is part of Shifting Between by Our Softest Hour at Blk 9, Gillman Barracks (ongoing until 30 Jan 2021).

*A previous edition of this article did not include mention of Maybe we read too much into things by curator Berny Tan. We apologise for this editorial error.