“I’m a strong advocate and believer in physical interaction and connection,” says Cambodian artist, writer and curator Vuth Lyno. “I believe that even though the world is becoming increasingly digitalised, it is our human condition and nature to crave for physical connection. That’s how intimacy and trust can be meaningfully produced.”

Audience participation and community-building have always been central ideas in Lyno’s practice. They are also at the core of his new show at MIRAGE Contemporary Art Space in Siem Reap, which is currently ongoing until 22 February 2021. Titled Sala Samnak, the exhibition explores through light installations and paintings a traditional communal space that exists throughout Cambodia: sala samnak, a rest hall. The artist evokes the evolving social function of these structures, in conjunction with Cambodia’s hasty economic and social growth.

Walking into the space, visitors are faced with a floating architecture constructed out of neon light. “I wanted to create a magical quality of encounter with the audience,” says the artist. “An imaginary or otherworldly experience, an image that exists in our mental space or memory.” To record their personal perception of the space, visitors are invited to write about their experience in a physical and online guest book.

We speak with Vuth to find out more about his thoughts behind this work.

Is Sala Samnak a development of a previous research and reflections, or is it new work?

I started looking at sala samnaks several years ago. I was interested in this Cambodian model of building communal and public spaces by the villagers as a gesture of generosity. It’s a collective offer to the society. I was in fact thinking of connecting this form of building relationships through sala samnaks with the idea of sharing knowledge. I wanted to do a project where I could travel with some people to different places in Cambodia and stop by at different sala samnak where we could hold a discussion with some local specialists knowledgeable on different topics. However, because of COVID, I couldn’t, so I have been researching light and sound for my artistic practice. I came to be fascinated by neon light as a medium.

The works of light installation and paintings are a collaboration with Kong Siden, Prum Ero and Than Sok. How did the collaboration occur?

In my practice, I tend to work with other people in realising the final work. I find it’s more rewarding to work and collaborate with various people and together we can bring out the best of each of us and produce something compelling that perhaps each of us couldn’t achieve single-handedly. So I asked Kong Siden, who is an interior designer and visual artist and my colleague at Sa Sa Art Projects, to join me in developing digital sketches of the light installation of Sala Samnak. I then invited Prum Ero who is meticulous and technical savvy and has interest in light to be on board in the technical aspect of production and installation. And for Than Sok, he has previously worked with me on my “House – Spirit” project. His practice has often concerned spirituality and beliefs. So I asked him to produce some paintings.

How the significance of the sala samnak in Cambodia has changed over time, and do you have personal memories tied to them?

Sala Samnak has a mixed relevance these days. It is still strongly practiced in rural settings, but less so in the urbanised context. This idea of a rest hall was also translated in a modern form in some of the public buildings and architecture built post-independence, such as the shady area on the top of the soccer ring at Phnom Penh’s National Sports Complex. It has been and still is a popular place for hanging out, eating, and doing exercise. I went there with my father to exercise when we lived close by when I was little. I also remembered stopping by one of these sala samnaks in the province waiting for our transportation. Now we see some sala samnaks are abandoned, neglected, and left to decay by the street side. But in some villages, people are building new ones. Perhaps this is a usual cycle. However, I hope that this practice is not erased by urbanisation. I think we should learn from this idea of building space for the public.

Light, darkness and empty space are the backbone of this show. When did you first start experimenting with these elements in your practice?

My practice has often dealt with space architecturally. For example, my first work of Thoamada (2011) was a circular installation of suspended photographs where the audience can experience the work from either outside or inside the work. I’m particularly interested in designing a space to produce a certain kind of experience for the audience. In the case of the Thoamada installation, the audience could first observe the portrait photographs from the outside of the circular installation. However, when they view the photographs from the inside of the installation, the dynamic of roles being “observer” and “observed” are reversed, as the audience becomes observed by the photographs looking in at them from different directions.

In Light Voice (2015), I renovated a staircase at the White Building in Phnom Penh, and installed strips of LED light and radios. It used motion sensors so the light and the radio would activate when people passed by. It wanted to transform the otherwise neglected and intimidating dark space in the staircase, into a friendly environment for the residents, while highlighting the original architectural design of the building.

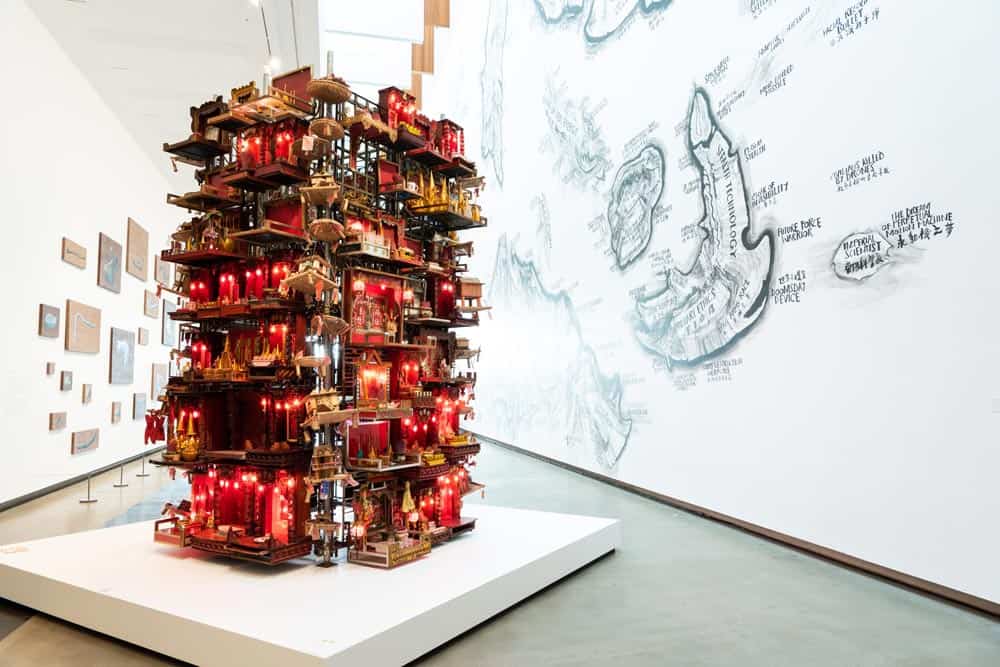

In my more recent work House – Spirit (2018), I created an installation of 119 spirit houses that I collected from the White Building when the residents were moving out before the building’s demolition in 2017. It was a shrine of shrines, a collective spirit – both conceptually and literally – and families’ histories from this neighbourhood. They are installed on a tower structure made of used door and window grills from Phnom Penh. Many of the sprit houses had functioning lights on. At night with the lights on, the energy of the spirits is remarkably felt. So it gave me an idea of using light for my future work, but this time I wanted to use only light as the structure and as the work itself. Indeed Sala Samnak (2020) was conceived as a total light structure.

Due to our globalised world, and the pandemic of COVID, many art experiences are increasingly happening online. As a strong believer in physical interaction with audiences, how do you manage to keep the virtual and the in-person participation balanced, in terms of the fruition of artworks?

I feel the shift towards the virtual is inevitable, and something that I’ve been thinking more and more in my practice. I want to find a way to bring about both the physical and the virtual to enrich our experience of fruition overall. That way, perhaps we could find a new compelling way to engage with art.

______________________________

Sala Samnak is showing at MIRAGE Contemporary Art Space, Siem Reap, until February 22, 2021.