A collection can represent many different things; it can be a statement, contribution, research, even a love story. In the case of retired German doctor, Christoph Bendick, who has worked in Phnom Penh for 25 years, it’s the story of an encounter with a country whose painful recent history is interlaced with the resilience and strength of its people.

The term “Year Zero” refers to 1975, the year in which political leader Pol Pot declared the purging of all culture and traditions in Cambodian society upon the Khmer Rouge’s brutal takeover of Cambodia.

Learning about the stories of the artists who have rebuilt the visual art scene from the ground up after the devastation inflicted by the Khmer Rouge between 1975 and 1979 has challenged and re-defined the collector’s perspective on art. It was also a step in setting aside the eurocentric gaze to expand his view of art and art history for Bendick, who also holds an MA in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Cologne, Germany.

Bendick was introduced to art at a young age by his mentor, the late artist-school teacher Edgar Hofschen. Influenced by Hofschen, who had been a representative of analytical painting, Bendick’s artistic preferences were initially oriented toward a formalistic, “art for art’s sake” kind of approach.

“I was brought up seeing art as a decorative pastime, something to grace the walls… [and] was fascinated by the idea of focusing painting on something that shows only itself, and has no any relationship with the world outside,” says the collector. His early core interest was in artists like Raimund Girke, Ulrich Erben, Antonio Calderara and Daniel Buren – to name a few.

Bendick began acquiring Cambodian art from 1998 after having moved to Cambodia in 1994, collecting works that reflected the nation’s political, historical and social issues through the eyes of the local artists, as well as works of a more abstract, formalistic nature.

We speak with the Christoph Bendick about his method of collecting, his observations of the Cambodian art scene and his favourite artworks.

Collecting Cambodian contemporary art has given you the opportunity to experience and participate in the process of re-developing an art scene after its destruction at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. How did your role as a collector change over the years as the local scene evolved?

When I came to Cambodia in 1994, I got in contact with the late Svay Ken, a central figure in the re-emergence of Cambodian contemporary art, rather by chance. Having survived the horrors of stone-age communism, large parts of his work are dominated by what he had gone through and how he and his family coped with it.

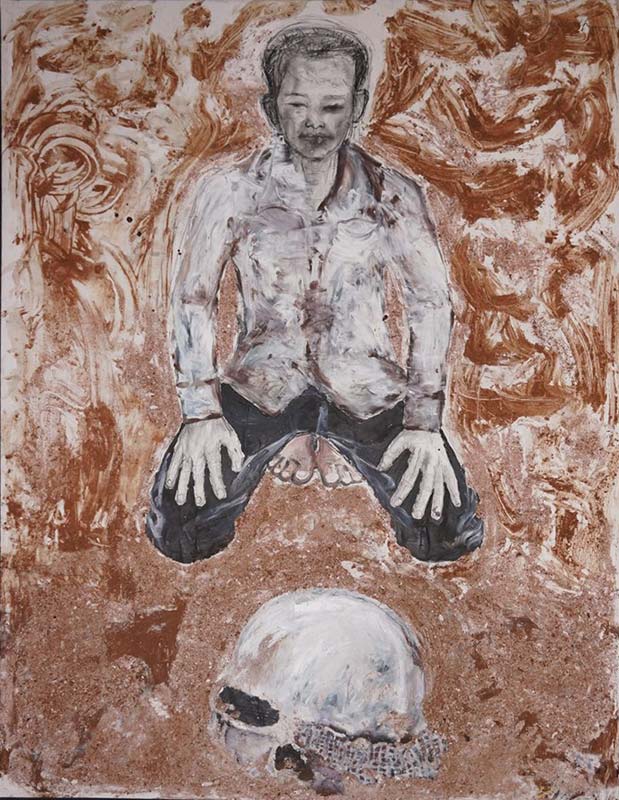

My first major purchase was Chea Serei Roath’s Auto Portrait with Skull, a haunting reflection of the toll that the Khmer Rouge had taken on his country. Later on, I became less afflicted with coming to terms with the past (an all too well-known topic given my German background). Instead, I had the opportunity to witness the unfolding of the art scene towards greater diversity with regard to topics, styles and concepts. Still, Cambodia’s traumatic history plays an important role for contemporary artists as well as for myself as a collector.

Before moving to Cambodia, your art collection focused more on European and American art and it looked much more formalistic. Cambodia introduced you to an alternative view of art, as something connected to society and its developments. Could you share how your perspective has changed?

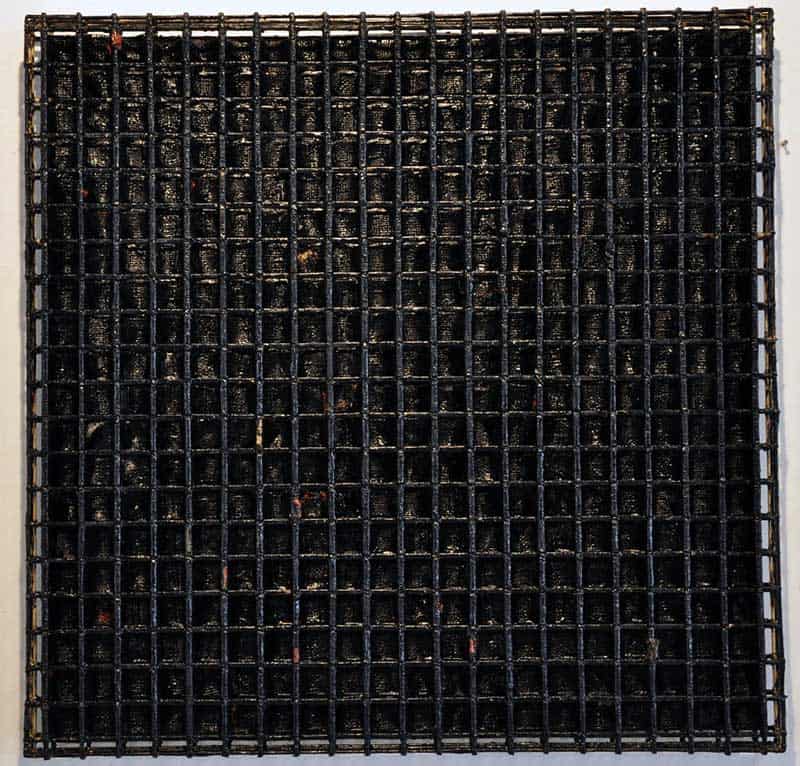

Coming from analytical painting, I was very focused on non-objective art, disregarding anything objective. For many years my artistic icon used to be Malevich’s Black Square. Naturally, with increasing maturity and experience, this attitude was put into perspective but it was only in Cambodia that I realised fully that art cannot be detached from the context and conditions under which it comes into being. While the Khmer Rouge regime and its aftermath played a pivotal role, I also realised how social and individual circumstances like disease, poverty, isolation and political pressure shape art.

Today, your first approach to an artwork is based on an emotional rather than an intellectual understanding. You’ve said that your thought when collecting is: “What touches my heart; to what do I feel a strong attachment to?” Could you share some instances in which you encountered work that deeply moved you?

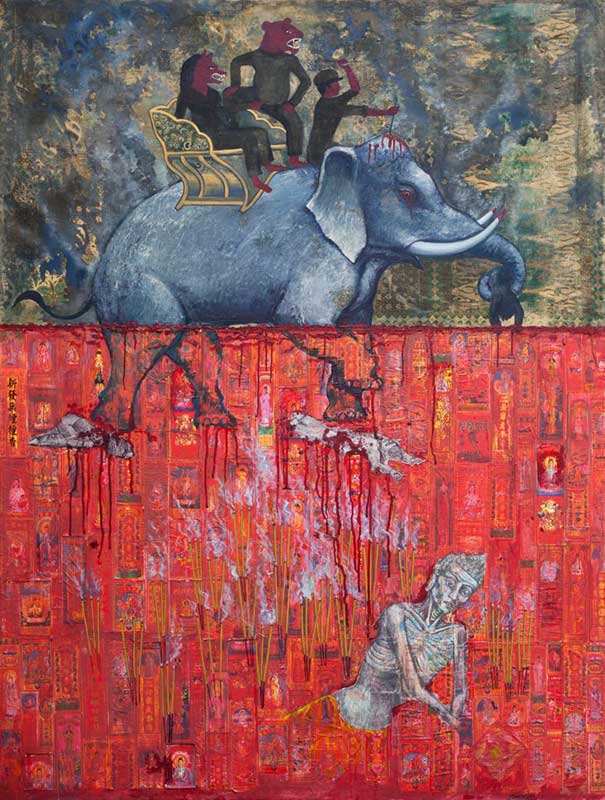

From my Cambodian collection, I need to point out Leang Seckon’s Elephant in the Pool of Blood, as its emotional effect is hard to resist. It depicts monsters in Khmer Rouge attire, men trampled to death by a tortured elephant, and a mourning Buddha.

Another example is Khvay Samnang’s Preah Kunlong, which features preeminent Cambodian dancer and choreographer Nget Rady in the wilderness of Areng Valley, part of a southwest province of Cambodia. He is wearing a crocodile mask which was produced by local villagers.

How do you personally reconcile a westernised meter of judging the quality of artworks, versus the necessity of encouraging a havocked art scene to develop in its own timing?

As a rather privileged European I have had the chance to go through high school and university, not to mention countless visits to international museums and galleries. When I came to Cambodia, I had the unrealistic expectation that a young Cambodian artist should at least have a solid understanding of names and styles which shaped 20th century art.

Later I became more sympathetic, realising that not everyone grows up in the circumstances that many Westerners do. Furthermore, there are a number of cultural aspects which I have no knowledge about, such as indigenous music, literature and visual arts that are quite unknown in the West. The overwhelming importance of Angkor Wat to the Cambodian national psyche and the continuing burden of the Khmer Rouge period upon generations were also cultural issues that I learnt from the Cambodian perspective. We Westerners tend to have the ethnocentric view that the world should understand occidental forms of expression, yet all too often we do not necessarily strive for a deeper understanding of other cultures.

In this process, how important is it to meet artists in person?

I enjoy meeting and keeping in contact with them but it has little influence on my attitude towards their work. In principle, I think that works of art must be self-explanatory, and only in selected cases should the artist’s commentary be required to understand them.

What are some relevant developments you have observed across different generations of artists in Cambodia?

From rather tentative and provincial beginnings, mostly under the guidance and encouragement of Western collectors and gallerists, the Cambodian art scene has changed a lot since I first began surveying it. There is now greater diversity in terms of styles, techniques and topics, and artists have greater independence and confidence in dealing with collectors and gallerists. More extensive networking is also occurring within Southeast Asia and the Cambodian art scene is gradually opening up to international institutions.

An excellent example of this is Sa Sa Art Projects, a Cambodian-run art space in Phnom Penh covering a wide range of exhibitions, lectures, artistic events and scholarships.

What are the central political, historical, and social issues that are reflected in your collection?

I hardly collect thematically. That notwithstanding, Cambodia’s recent history plays an important role. And as a physician I also look out for artwork dealing with aspects of disease and disability or the shortcomings of the health system as can be found in Sao Sreymao’s digital drawing Sickness.

However, the quantitative and qualitative focus of my collection is certainly on the work of Pich Sopheap, whose conceptual approach can hardly be presumed to be influenced by political, historical or social aspects. In this respect, I’ve come full circle with my very earliest interest in formalism.

You have now relocated to Germany. Do you have plans to spread knowledge of Cambodian art in Europe by making your collection public?

For the time being, it is a private collection but I am working with a curator on reviewing the collection in order to prepare a publication. Hopefully this would lead to a better understanding of Cambodian art in Germany, which so far is relatively neglected. If this could eventually result in a museum-exhibition, I would be even more satisfied.

___________________________________

Find out more about Christoph Bendick’s art collection via his website.

Feature image: Portrait of Christoph Bendick. All images are courtesy of Christoph Bendick.