“The studio is where strange magic happens, as much for the artist’s imagination as for the public’s. It’s the conjuring place of new concepts, styles, or forms.”

– George Philip LeBourdais

This article is part of a series of interviews with artists in their studios, in which we attempt to explore artists’ working habits and the places that nourish them.

Think of Singapore’s contemporary art scene, and one of the things that might not come to mind is the medium of batik and its rich connections to Javanese culture. Hoping to change this is artist-curator-educator Fajrina Razak, whose immersive batik artworks explore notions of spirituality and identity. She’s also the founder of 405 Art Residency, where she champions the use of batik in the art scene today by inviting emerging artists to try their hand at the medium. On top of all this, Fajrina is also President of Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (APAD), where she strives to promote the development and appreciation of visual arts.

Starting this October, you’ll be able to get a behind-the-scenes look at the studios of artists and makers such as Fajrina with Grey Projects’ Walk Walk Don’t Run programme. Fajrina will be opening her studio on 6 November, which will provide an insight into batik’s intricate processes as well as the multiple roles she plays in the local art scene.

In anticipation of Walk Walk Don’t Run, I speak with Fajrina on her experiences with her studio space, what she hopes visitors will take away from visiting her studio, and her spiritual relationship with the labour-intensive medium of batik.

What’s your studio space like?

My studio is in Telok Kurau Studios, which is run by the National Arts Council. It also used to house LASALLE College of the Arts many years ago and Telok Kurau Primary School in the 1940s.

I’ve been doing multiple things in the space. Aside from my practice, I run 405 Art Residency; its first cycle ran from December 2020 to March 2021. It’s something I’ve always wanted to do, even before I moved into this studio in February 2019. Even with Covid, I wanted to help emerging artists during this time and share my resources — in particular, space, materials, knowledge, and funds — with those who might not have them.

I thought I might as well let them try out batik, especially since there aren’t many contemporary artists practising this medium. This is mainly why I chose to open the residency even though it’s just a short-term programme. It will open again at the end of the year. My hope is that artists who undertake this residency will experiment with batik and see how they further develop the medium in their own practices even after the residency.

My studio also houses the non-profit art group APAD’s archive for now, as I’m currently digitising their archive.

What are some of your favourite things about your studio?

The studio is in an isolated area, so it’s quiet. My friends who come over ask me if I’m scared of working here at night. I don’t think about that, because I just need some time away from how busy the rest of Singapore is.

What are you working on right now?

Besides digitising the APAD archives and preparing for APAD’s upcoming exhibition, REWANG, I am also in the planning stages for series of exhibitions next year to commemorate APAD’s 60th anniversary. This is a task that I have been working on with APAD’s management committee since I took on the role of President in February 2020.

How did you become the President of APAD and what do you hope to achieve during your time in the role?

I joined APAD as a member in 2010 when I was a fresh graduate. APAD was one of the platforms for a young artist like me back then. Then, I held the roles of Treasurer from 2016 – 2018 and Honorary Secretary from 2018 – 2020, before being elected as President in 2020 at our Annual General Meeting.

As President, I’m heavily involved with running the association, be it through undertaking administrative duties, organising exhibitions and managing projects. Now, I’d like to take this opportunity to recruit younger members to join APAD and be involved in its continuity. I also hope that by holding more critical exhibitions in the future, APAD will remain relevant in the local art community.

You’re participating in Grey Projects’ Walk Walk Don’t Run programme, which invites the public to come to check out your and other artists’ studios in November. What can visitors expect to see then and what do you think they might gain from the visit?

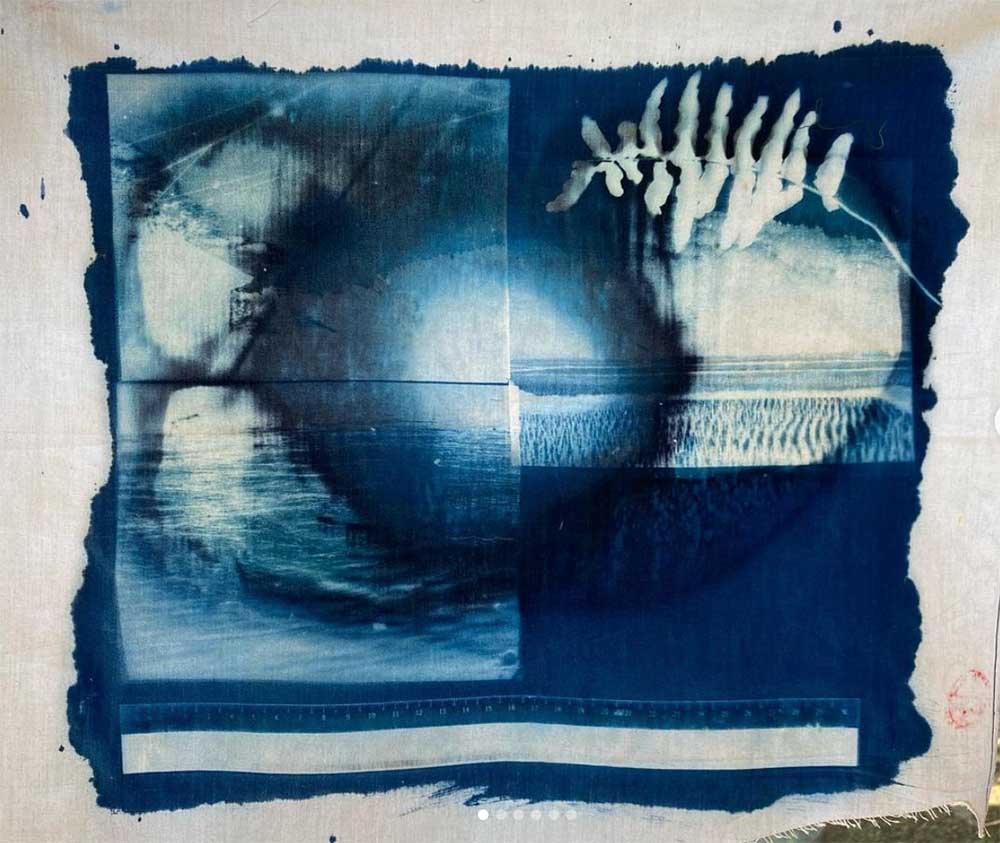

Visitors will get to see my works in progress. That would include my tie-dye and wax-resist works, as well as my Graphing Mountains series. That series came about last year and was exhibited at the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre in March 2021, so I’m expanding on that. I will also be leaving a few works immersed in dye baths, so visitors can get a sense of the batik-making process.

Aside from those, I also used to work with photography. I might jump back into that this year and include some photography works for REWANG, so visitors might be able to see that. Hopefully, I have time to try that again!

Your practice is concerned with individuality and cultural identity, as well as the questioning of personal histories. How does batik, a fabric with such a rich cultural history tracing back to Java, enable you to explore these ideas?

Batik is a medium that I’ve always wanted to work with to get in touch with my Javanese roots. At the same time, as a Singaporean who doesn’t speak Javanese, I feel conflicted about my own identity. Being in multi-religious Singapore, I find this medium sacred as it’s been practised for thousands of years. When I practice batik, I work with an embodied knowledge that lets me delve deeper into my roots, my teachings on spirituality, and how we practice spirituality beyond religion.

There are many ways to practice spirituality. My form of spirituality is batik itself.

Beyond using the medium, I also think about living in a place surrounded by neighbouring countries that practice spirituality differently. As someone who lives in rapidly developing Singapore, sometimes you just need to step back. I use batik to break away from such fast-paced life.

The binary of the visible and invisible is also present in your work, as you contrast explorations of emotions and spirituality with the tactile, physical, and labour-intensive nature of batik. How do you reconcile the two?

My work revolves around my thoughts and emotions, so that’s how the text in my work comes about. A medium like batik doesn’t allow you to be direct in your art-making, especially when you compare it to mediums like acrylic or oil painting. Being a medium with a longer process, batik allows me the time to reflect on my thoughts and materialise them onto the fabric. I feel it’s an innate necessity for humans to materialise our thoughts and emotions.

What’s something that audiences might not understand about your process from just seeing your finished works at an exhibition?

They should see how messy and fussy batik is! Whenever I see my completed work at an exhibition, I feel like there’s this invisible process people don’t see. Usually, in a factory, a group of people work on and finish a piece of fabric. So it’s as if I’m doing five people’s worth of work, and it’s even more tiring when you’re working on a large-scale piece. I’m usually in the studio from morning until late at night as I need to complete the boiling and drying. Only then would I be able to work on the next steps like colouring and waxing the next day. These processes aren’t usually talked about enough.

You’re also the founder of 405 Art Residency, an initiative that enables artists to develop their artistic practices in a batik-making space. How did this come about and what do you hope to achieve by giving space to the medium?

The project began when I was thinking about how to let more emerging artists get to know batik, as it isn’t practised much in the contemporary art scene. However, this was more popular in the modern art scene in the 1990s, where you had artists like Jaafar Latiff and Sarkasi Said, working with it. There’s a lack of batik practitioners in the contemporary art scene, which made me realise there’s a need to open a place with the resources I have to ensure the continuation of batik practices.

It’s also a form of heritage and I don’t want to see it decline. It might seem traditional but it’s also a medium with a lot of room for innovation and experimentation. You can combine it with other mediums or use aspects of it, such as wax and dye, to create something new. For me, I want to see how batik can be innovated and take on other forms.

Aside from being an artist, you wear multiple hats in the industry as an educator, curator and residency manager. I’m also particularly fond of your most recent curatorial project with Syaheedah Iskandar, Between the Living and the Archive at Gillman Barracks! Can you tell us what value the various roles bring to your practice and how they intersect with each other?

As an educator, I teach batik at primary and secondary schools. I usually impart the practical skills involved with batik, but I also try to teach batik with a local perspective in mind — even though batik is derived from the Javanese people. This makes me think how batik might be shaped through the Singaporean identity and how batik belongs to me as a Singaporean and Malay person.

On top of that, Between the Living and the Archive expanded my practice as we explored notions of embodied knowledge and how artists presented their own lived experiences. Then, it occurred to me that what I do at 405 Art Residency is also a form of knowledge-sharing. Those artists in the exhibition worked with materials that became archives, as the materials were an extension of the artists. That’s also how I see my work and practice.

These projects have led me to consider the ethics of approaching knowledge and mediums such as batik, and how we might work respectfully with materials from other mediums and forms of knowledge.

_____________________________

Continue the conversation about batik with Fajrina Razak at Grey Project’s open studio event, Walk Walk Don’t Run. It starts on 23 October 2021 and will run for four Saturdays in October and November. To find out more, click here: https://www.greyprojects.org/walk-walk-dont-run

APAD’s exhibition, REWANG, is showing from 20 October to 5 November at Maya Gallery. For more information, click here: https://www.facebook.com/apad.sg/

Feature image: Artist-curator-educator Fajrina Razak in her Telok Kurau studio. Image courtesy of the artist.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.