It is a breezy Saturday afternoon in February when I make my way to Tanglin Halt estate in Queenstown, Singapore.

Completed in 1962 and 1963, large sections of the estate have been earmarked for redevelopment by the Singapore Government under the Selective En bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS). In 2014, the Housing & Development Board (HDB) announced that it would build some 3,700 new flats in Dawson estate as replacement flats for the residents of Tanglin Halt estate, with residents being able to choose new homes from five replacement sites in Dawson, as well as homes in other HDB developments.

On the day that I visit, it seems that a number of residents have already moved out and not many remain. There are a few people meandering slowly through the walkways, plastic bags in hand, and random small groups sitting in the quiet corners chatting to themselves. The skies are overcast and the estate looks a little gloomy, but the cooler weather also means that residents can sit outdoors comfortably to shoot the breeze. Almost all are elderly. There are pockets of rubbish and unwanted furniture lying about the estate, a melancholic mess of discarded memories and detritus.

Artist Calvin Tay explains wryly, “if you like to scavenge for furniture, this is a great time to come because everyone is just vomiting their stuff out of the flats.”

I’m here to visit Tay’s show Taking Routes which — although located in a flat in Tanglin Halt — essentially turns the entire estate into a museum and art gallery of sorts. Before or after visiting the show, you are encouraged to take a walk around the neighbourhood and as you do, vibrant impressions of the estate’s past life in all its technicolour glory, start to emerge.

A quick walk around the estate might yield more questions than there are immediate answers for, but head on over to Block 28 and you’ll be greeted with Tay’s unique love letter to Tanglin Halt, one that’s expressed through a series of three–dimensional artworks made of thermoplastic Hot Melt Adhesive (HMA).

When art meets life

Tay himself spent time at his grandparents’ flat in Tanglin Halt as a child and has deep-seated memories rooted in the estate. Preoccupied with thoughts of how the estate would be remembered once demolished, Tay embarked on a project to gather familiar routes taken by residents as they had moved around within it, while it was still functioning and bustling with life.

He spoke to members of his family who lived in the area, as well as their friends and contacts. Looking to social media, he posted requests for residents to be referred to him, to outline and map out their most commonly taken routes in Tanglin Halt – be it to school, the MRT station or to places of religious worship.

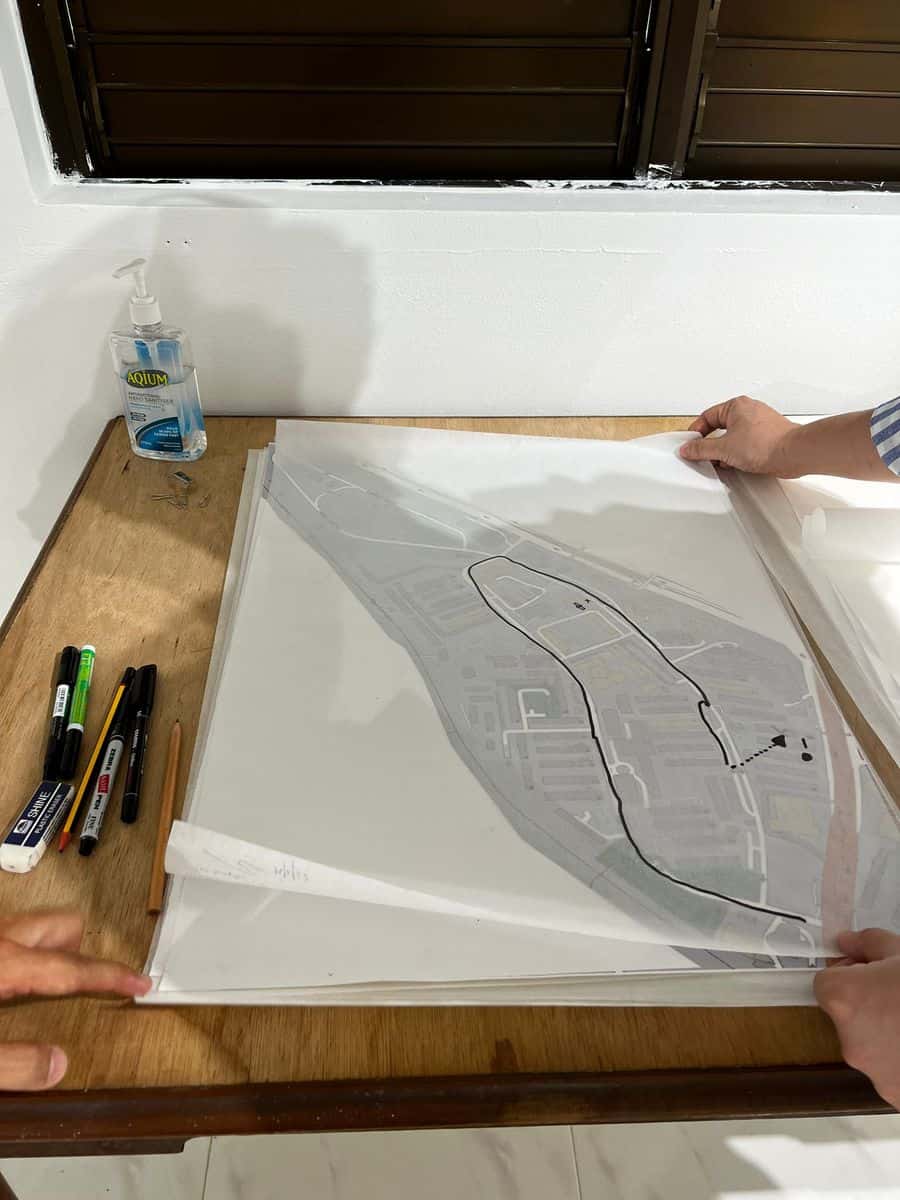

Nothing was too quotidian for Tay’s inquiry. In fact, the more quotidian, the better. In one particularly idealistic turn, Tay admits that he sat in the Tanglin Halt Food Centre armed with his maps, pens and tracing paper, absolutely convinced that he would be bombarded with curious queries by residents about his artistic endeavours. The idea was to get residents to chat with him, and trace out their familiar routes in the estate on tracing paper placed over a map of the estate.

The reality, he laughs, was quite different. “I sat there with my maps in the market and I thought people would just flock to me, but after sitting there for one or two hours, I only managed to get two small lines. But I had to talk to people, and they would tell me all these stories about when they used to live here.”

“One uncle just wanted to share stories with me about the best food in the area,” he chuckles.

The works in Taking Routes are subtle but eye-catching, and even more profoundly moving when you hear about Tay’s production process. After gathering the commonly-walked paths mapped out by residents of Tanglin Halt, Tay grouped common routes together on canvas and painstakingly ‘drew’ them out with HMA, over and over again. The result is slightly raised, relief-like works which resemble topographical maps viewed from above.

There is a hard smoothness to the works that evokes a sense of ossification. The works are shiny and their white plasticky veneers create the impression that Tay has somehow managed to shrink wrap and preserve forever, the fleeting everyday lived experiences of the residents of Tanglin Halt. It’s a wonderful crystallisation of a specific moment in time, rendered with delicate care and after a period of detailed and painstaking research. With his artistic tools, Tay’s managed to turn the old memories of a dying estate into something new and shiny.

In another room, a time-lapse video plays, showing physical re-creations of the routes captured in the artworks from different vantage points around the flats.

The commodification of nostalgia?

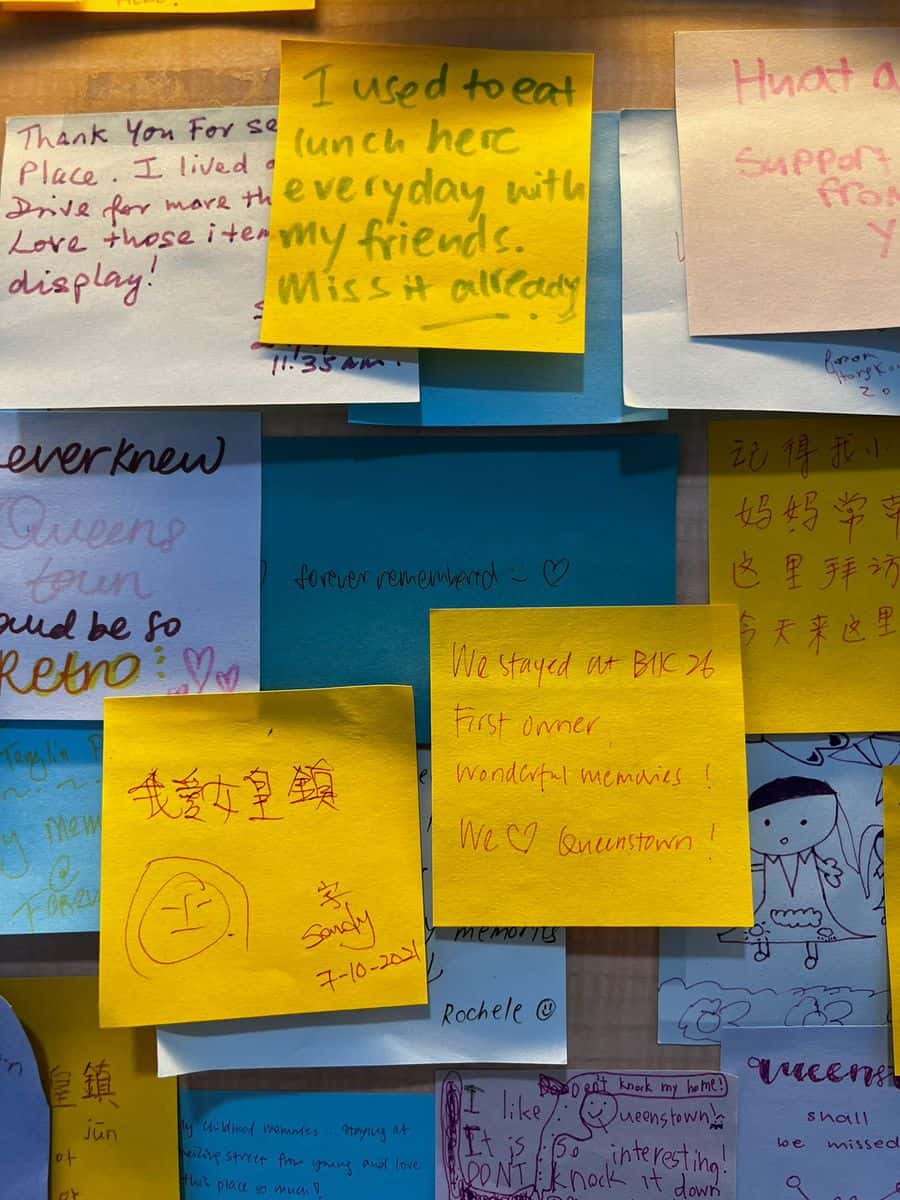

One might wonder — what about the spectacle of the whole thing? Was it right, or even ethical perhaps, to set out with an intent to draw art lovers to gawk at an estate and its residents in its sunset years? Tay tackles the question head-on and emphasises that his intention was to share the memories of the estate with the wider Singapore community and to reiterate the point that “HDB estates are really the heart of Singapore.”

Indeed, his intentions are bourne out by the entire visitor experience — there are no obvious signs or group tours of the estate and the art exhibition is located behind a discreetly shut door. There is no actual gawking to be done, just a quiet appreciation of the crowdsourced memories that Tay has obtained from his research and manifested through his intricate artworks. When I ask him how existing residents reacted to his show, he laughs and reckons that they are “really not that interested in these abstract things.”

“I went back to the market to ask the uncle to come (to this exhibition) and he was like ‘who are you?’”

“He couldn’t even recognise my voice, or remember me,” Tay recounts.

He also openly acknowledges the ironies in his nostalgic foray as some residents themselves seem to prefer new and shiny buildings and a more comfortable and modern way of life. When Tay explained the premise of the show once more to the said uncle, he replied, “My route is not important, why don’t you go to Dawson? People are happy and there are a lot more things there.”

The show manages to tease out the ever-present tension between modernisation and the fetishisation of nostalgia, prompting visitors to question who exactly benefits from urban redevelopment. It makes the important point that perspective is everything, and that one man’s hipster coffee joint may well be an old-fashioned hellhole that another can’t wait to escape from.

A guestbook with a difference

Visitors to the show are also invited to partake in the mapping of their own Tanglin Halt paths while en route to visit the exhibition.

“Instead of writing in a guest book, you can trace your own route on a map of Tanglin Halt. Tracking your route from a top-down perspective is quite different from visualising it laterally as you walk,” says Tay.

Without a doubt, there is a respectful observance of the lived histories and shared memories of the community, evidenced by Tay’s own personal association with the estate. Tay explains that while the idea was to “capture residents’ routes rather than their way of living,” visitors would invariably end up making parallels between their own lived experiences in HDB estates and the paths mapped out in Tay’s works.

Taking Routes offers a wonderfully complementary experience to the existing Museum@My Queenstown, a community museum located not far from the art exhibition. Run entirely by volunteers and funded by donations (with no government funding whatsoever), the museum collects stories and old photographs from the residents in the area.

Tay tells me that he hopes his show encourages people to visit Tanglin Halt before its buildings are demolished, especially people who wouldn’t usually come to the estate. It’s an exhortation that I’m happy to get behind as Taking Routes offers a smart and sensitive journey into Singapore’s more recent community history — it’s a trip to be savoured and enjoyed before the buildings come down and the landscape changes once again.

____________________________________________________________________

Taking Routes runs till 4 March 2022, but visitor numbers are now restricted due to Covid – 19 safe management rules. Find out more about the show, contact the artist, or view the exhibition online here.