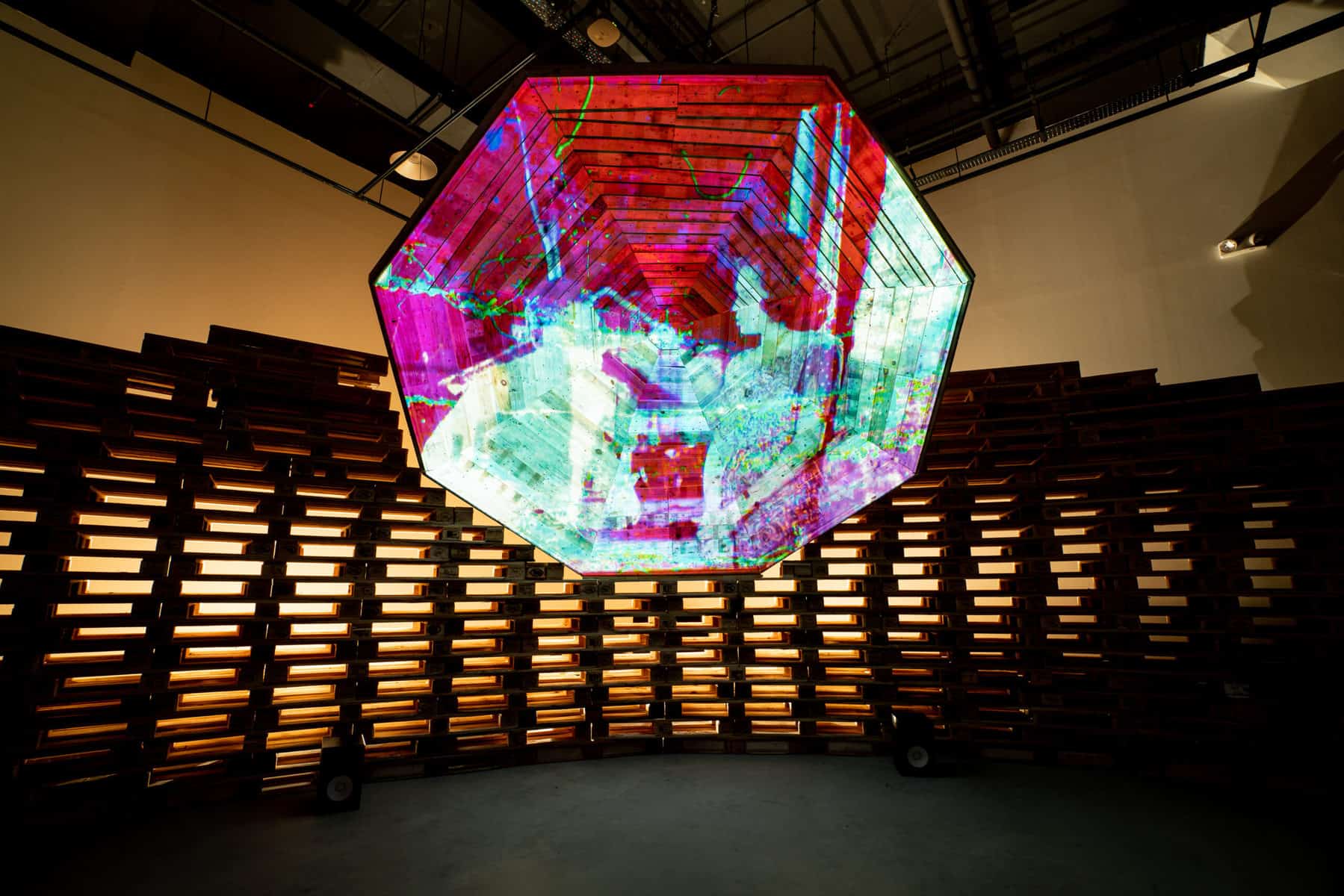

In a cavernous industrial warehouse in Tanjong Pagar, a strange, almost subterranean landscape unfurls. Tessellated wooden structures divide the darkened space, the pockets of space between them aglow in amber light. Out of this faintly dystopian universe rises an island-like platform littered with broken instruments. The air is thickly textured with fog and sound; alien vibrations pulse low in the distance.

This is a retrospective of The Observatory. Known affectionately as The Obs, the pioneering experimental rock and electronica band has been making waves in the local music scene since 2001. To my untrained ear, the band’s aesthetic is a little bit Radiohead, a little bit T.S. Eliot, darkly lyrical and gorgeously melancholy. But here, the stars of the show — current band members Cheryl Ong, Dharma and Yuen Chee Wai — are nowhere to be found, at least, not at first glance.

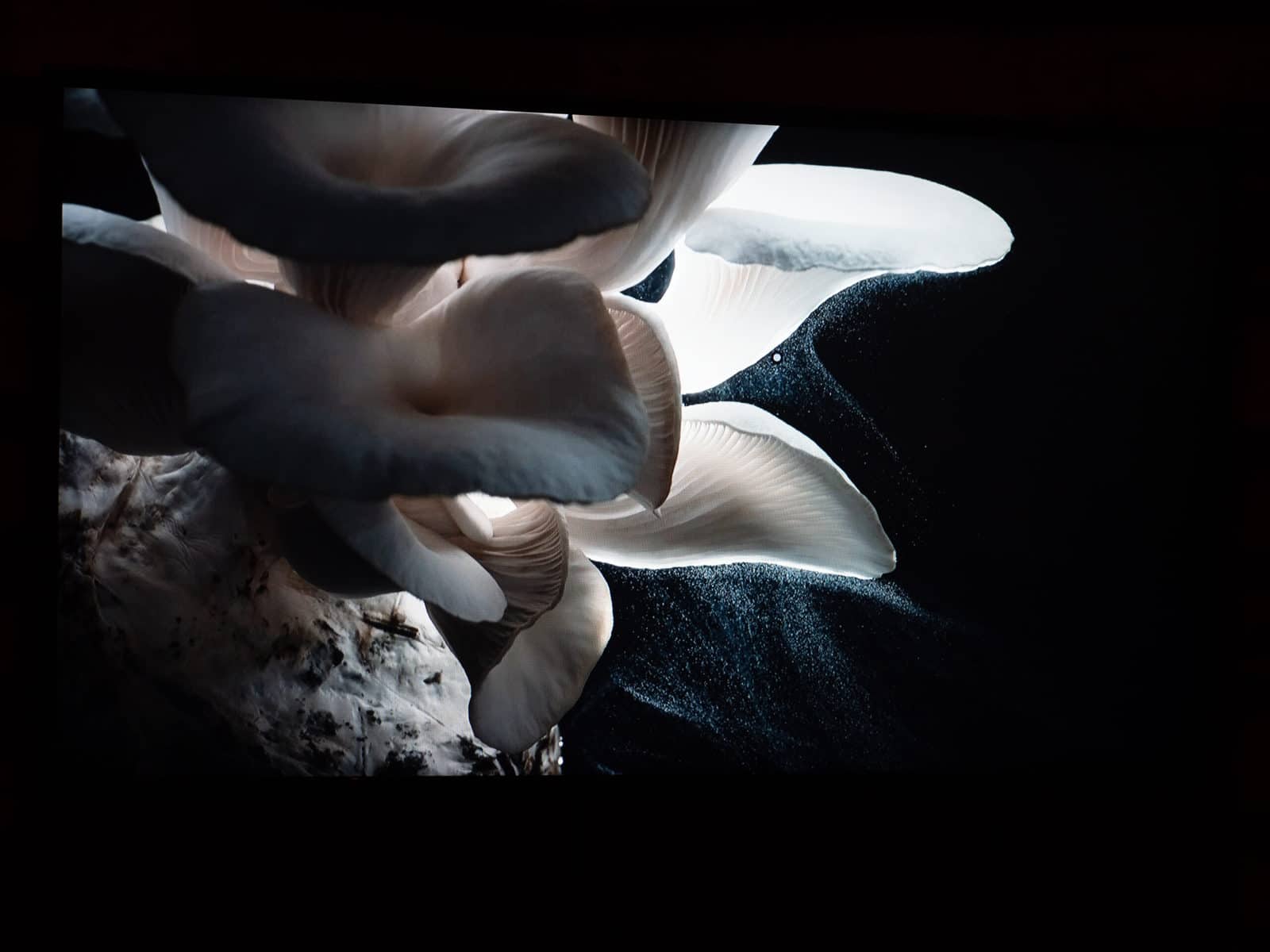

In their place are instead eight different species of fungi. Mushrooms sprout out of drum kits and broken guitars, leave traces of decay across film footage, and furiously metabolise within glass jars.

Casting these non-human actors as the protagonists of this immersive, multi-media installation was a pointed choice. The Observatory wanted to avoid an aggrandising narrative of their history, and so rejected a conventional retrospective of celebratory milestones, explained Chee Wai during his artist’s tour. This act of resistance is one of several meanings embedded in the exhibition’s title, REFUSE.

A collaborative ethos underlies this ambitious project. Instead of positioning the band as a singular source of artistic genius, The Observatory turned to the idea of networks, roping in collaborators from different fields — guest curator Tang Fu Kuen, mycology design studio Bewilder, installation artist Chen Sai Hua Kuan (Sai), independent record label Ujikaji, and director Yeo Siew Hua. The exhibition dives deep into mycelium, the underground, root-like structures that produce mushrooms.

The show’s title might also be read as re-fuse, suggesting a synthesis of existing material to create something entirely new. The Observatory could’ve easily written a new piece for their show at Singapore Art Museum, but instead, they chose to ask: what would relinquishing artistic control look like? How could decomposition be a means of composition?

Composition through Decomposition

At the centre of the “island”, mycelium in Petri dishes fuel a decentralised network of sound. If you look closely at the monitor, you’ll spot a couple of black dots quivering anxiously over a rugged white surface. These dots map certain parameters within the visual image, triggering sound and movement. Mushrooms whirl around on mechanical gizmos, twanging guitar strings, trembling ever so slightly against the taut skin of a drum.

The only part of REFUSE that touches on The Observatory’s history is tucked away at the back of the hall. But don’t expect to find a chronological timeline neatly laid out. Footage of the band’s past gigs are spliced and overlaid, while the audio plays from “sound domes” — large, clear, inverted acrylic bowls that resemble mushroom caps. Mindmaps designed by artist Debbie Ding and informed by fungal imagery are scorched onto wooden boards.

In keeping with the band’s refusal of authorship, this section is prefaced by mushrooms in a biosphere, which act as DJs. The electric currents they generate are fed into a digital processor that remixes snippets of The Observatory’s discography.

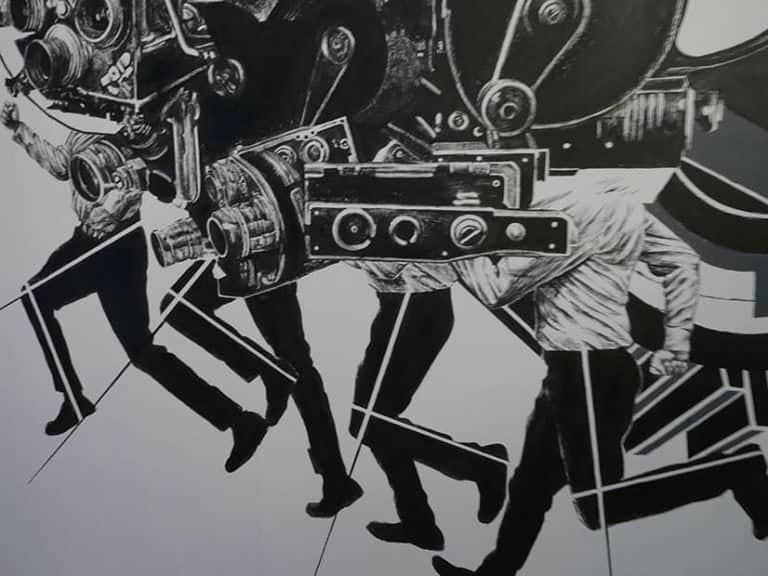

Decomposition and recomposition are everywhere in REFUSE. Record sleeves from the band’s past albums decay in a glass tank dotted with condensation, while a hallucinatory projection dances over two large, satellite dish-like domes at opposite poles of the hall.

If you’re a film buff, you might recognise the iconic Malaysian actor, filmmaker and musician P. Ramlee emerging between luridly-coloured, glitchy patches. The P. Ramlee film, which had gone mouldy with age, was foraged from the Asian Film Archive. Inspired by its gritty, grungey aesthetics, The Observatory worked with Yeo Siew Hua to enhance the mould using AI software. Siew Hua also laid some of his own discoloured film over the P. Ramlee original.

The result? A lush palimpsest of colour 60 years in the making, starring fungi as agents of decomposition.

Self-Sustaining Sytems

The cyclical logic of composition as decomposition structures the installation’s various self-sustaining systems. Across the hall, the P. Ramlee film is projected onto a jar of mushrooms. While mushrooms can’t photosynthesise, they are phototropic, which means that they metabolise more in the presence of light. As the mould eats through P. Ramlee’s film, the distorted projection feeds new growth.

Other mushrooms are wired up to lights, which are trigged once the levels of carbon dioxide in their jars reach a certain concentration, creating a cycle of growth. Put simply, the more CO2, the more light; and the more light, the more CO2.

I first visited the exhibition during Singapore Art Week, and then again in the first week of March. It’s astounding how much the mushrooms have grown. According to Chee Wai, the lids of the jars had to be re-secured because the mushrooms had pushed them open!

In REFUSE, non-human organisms assert their own agency against human parameters, through organic processes of change. And as the lights flicker on and off erratically, it becomes clear that the exhibition isn’t all about entertaining the human viewer, but about de-centring art’s anthropocentric tendencies.

What’s impressive about REFUSE is that while it is built on a great deal of scientific research, these technicalities are so well-translated they make sense on an intuitive, visual level. During the tour, Chee Wai frequently alluded to papers he had read about mycelium, throwing in scientific terms like “phosphates” and “symbiosis” as he unravelled the intricate workings of each set-up. But even with my secondary-two biology, I didn’t find it hard to follow his explanation, because I could see its logic right before me.

This is, I suspect, the reason why REFUSE has been so well-received by the public. While the exhibition is visually spectacular (and “Instagrammable”), it also stands on solid conceptual ground. You could simply see it as a show about mushrooms making music, or you could engage further with the heavy implications of spotlighting non-human actors, and of raising questions of time, matter and memory.

The Sound of Sustainability?

A large part of REFUSE’s draw is also, of course, its scenography. Weaving through the staggered walls of wood to enter the installation feels like stepping through a portal into an adjacent world, where raw earthy tones and textures rule.

“We were thinking about old furniture,” explained Sai, who designed and built these towering architectural structures from scratch. “Why not pallet wood? It’s a recycled, second-hand, re-used material.”

Working closely with Fu Kuen and The Observatory, Sai constructed miniature prototypes, visualising how the viewer might circulate the space and interact with the fungi. Strips of pallet wood from his neighbours (co-occupants of the industrial building where Sai’s studio is located) were rescued for his experiments.

Repurposing industrial detritus allowed the creative team to factor in the artwork’s afterlife even before it was born. Sai explained how the pallets would be disassembled and sold back to the company they were obtained from, re-entering the shipping and transportation industries.

The reclaimed pallets were also a nod to SAM’s new site — Tangjong Pagar Distripark. Here, you won’t be hard-pressed to find rows of cardboard boxes stacked on pallets around the neighbouring blocks.

The Observatory’s decision to work with Sai also made a lot of sense to me, given that Sai frequently engages with sound and everyday waste materials — refuse — in his practice. “I was doing a lot of sound research on my own, and so I brought in the idea of you being able to talk to yourself,” Sai recalled.

In fact, the empty dome towards the centre of the hall works as an echo chamber, amplifying the modulating sine wave in the gallery that pulses at 27 Hertz. This low-frequency atmospheric heartbeat belongs to a set of “spectrum peaks” in the Earth’s electromagnetic field, known as Schumann resonances.

In tune with the Earth’s hum, the sine wave acts as a sort of bassline to the immersive soundscape of REFUSE, inviting us to lean into the rhythms of life itself. As one of The Observatory’s songs goes, Everything is Vibration.

Art in the Age of the Anthropocene

What emerges throughout the exhibition is a new kind of seeing that unsettles our usual anthropocentric blinders. By inviting us to look at and listen from the point of view of mushrooms, REFUSE challenges us to rethink our relationships to the sentient, non-human beings that we share the planet with.

In many ways this questioning of our human-centric attitudes towards the Earth — attitudes that prioritise human welfare and development over all else — ties in with increasingly urgent ecological discourses.

You might have heard the buzzword “Anthropocene” thrown around in conversations on climate change, or chilli crab. Popularised by an atmospheric chemist in 2000, the Anthropocene refers to our current geological epoch, in which human activities have been a primary force in shaping the Earth’s ecosystems.

The Anthropocene is a call to realise how tiny human existence is on the grand scale of the Earth’s 4.54 billion years. It challenges us to re-calibrate our perceptions of time, tune into the Earth’s rhythms and fall in step with other creatures.

“To think of ourselves as biological organisms first, as one type among the worlds of other critters, allows for more open and curious relations to the other beings with whom we co-compose the world,” write Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin in Art in the Anthropocene.

For all its dystopian, post-apocalyptic undertones, this attitude of curiosity animates REFUSE. In a mesmerising two-channel video, tiny, luminous spores drift in swirling clouds from the undersides of mushroom caps. It’s hard to believe that these time-lapse videos are entirely CGI-free, because their beauty is so otherworldly.

REFUSE is a wholly aesthetic experience, one that heightens our senses to subtle sonic shifts and visual transformations. When we wonder at the beauty of glowing mushrooms, we reorient our senses towards a world that we share not just with other people, but with the teeming multitudes of non-human life.

Environmental art in Singapore

Looking forward, I do think that REFUSE represents an increasingly crucial direction for contemporary art in Singapore, as we fumble further into the Anthropocene. SAM’s immense support for the show, and the long list of supporters and collaborators credited, indicate the resonance of its ecological concerns.

And it’s not hard to name other shows that similarly grapple with how we perceive and construct the environment through various social, cultural, political and ideological lenses — Robert Zhao, Randy Chan and John Tung’s The Forest Institute, Donna Ong’s Somewhere Else: The Forest Reimagined, and Charles Lim’s Staggered Observations of a Coast.

The age of the Anthropocene is all too real for a tiny island facing rising sea levels. Yet, in our fiercely capitalist, tech-savvy, manicured garden city-state, “nature” and the “environment” occupy a particularly sticky place. We like our greens and waterfalls neat, indoors, looking pretty for the world, but not when it’s growing over planned MRT routes. As we sink ever deeper into the ecological crisis, how can art provide a counterpoint to the dominant narratives of human progress and development that have brought us here?

REFUSE offers a strong blueprint ahead, defiantly turning to waste and decomposition in a society that’s obsessed with untrammelled growth. In the words of the poet Paul Celan, “there are / still songs to sing beyond / mankind.”

____________________________________

REFUSE runs at Singapore Art Museum until 17 April 2022. Click here to learn more.