As dawn crept into day on my 29th birthday, a bus took me and other passengers from Phnom Penh to Siem Reap, the Cambodian province famous for Angkorian era temples. From that period, there are stone structures called agni grha, meaning house of fire in Sanskrit. These were places for worship and rest houses for pilgrims and travellers.

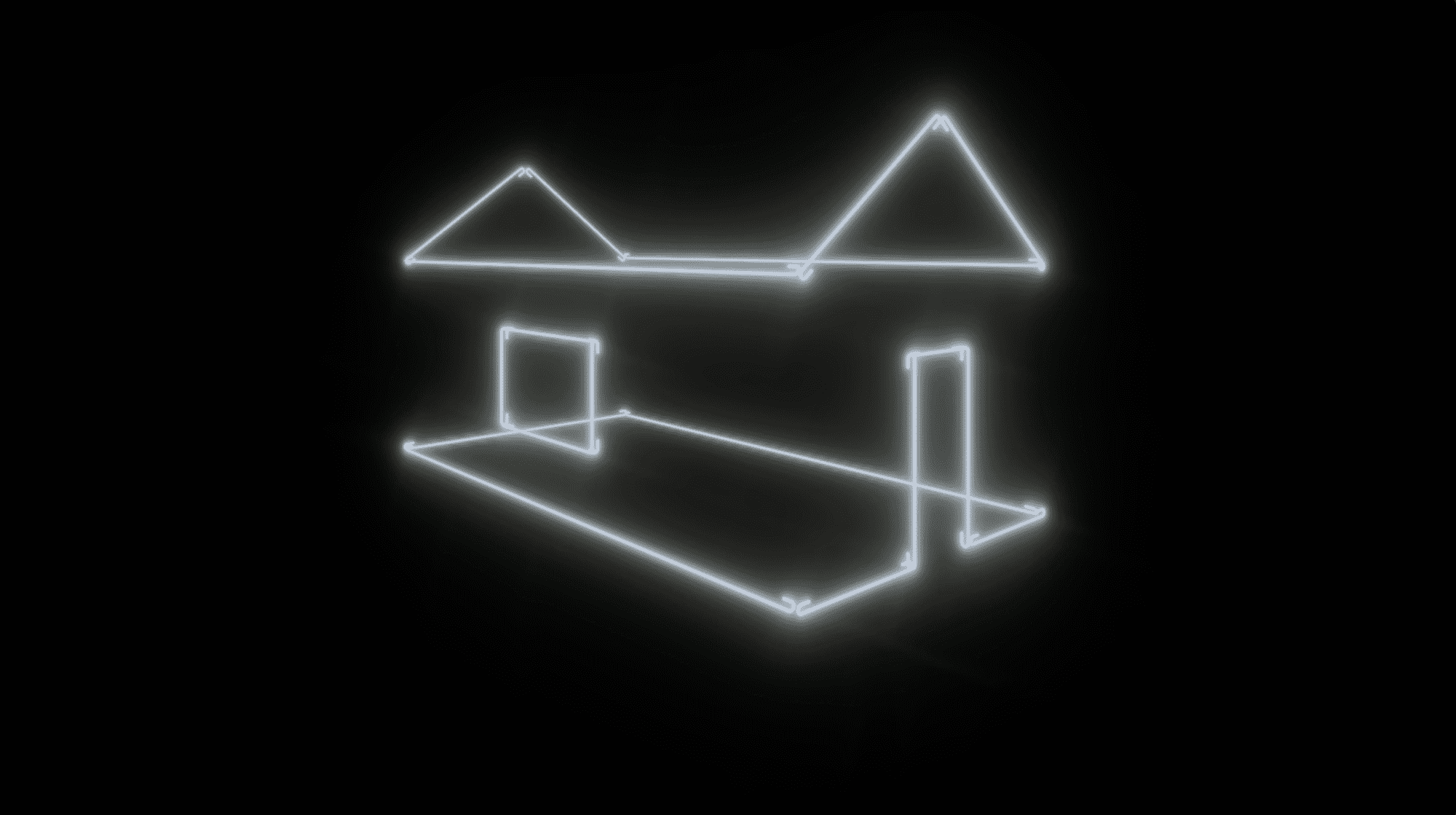

After the five-hour journey, I arrived in Siem Reap city, which was undergoing a major road renovation project. Despite the torn-up pavement, dust-filled air, and glaring sun, I walked to my destination, MIRAGE Contemporary Art Space. At the gallery, I was greeted by such reprieve from the elements that it seemed too fitting I had travelled to see artist Vuth Lyno’s light sculpture Sala Samnak.

The title of the artwork references the contemporary tradition of collective generosity that Cambodians offer society by building rest houses for anyone passing by. If this sounds familiar to the practice of agni gRha, that’s because it is. As Lyno elaborates, they share a cultural lineage:

“Travelling to pagodas for Buddhist ceremonies with my parents, I saw different forms of a sala samnak and how empty they usually were… On very few occasions the sala samnak was in dilapidated and neglected conditions. With this general understanding, I started researching and reading the work of anthropologist Ang Choulean. I learned this tradition dates to the Angkorian period and was called agni gRha. It is really something remarkable and of great value to the Cambodian community.”

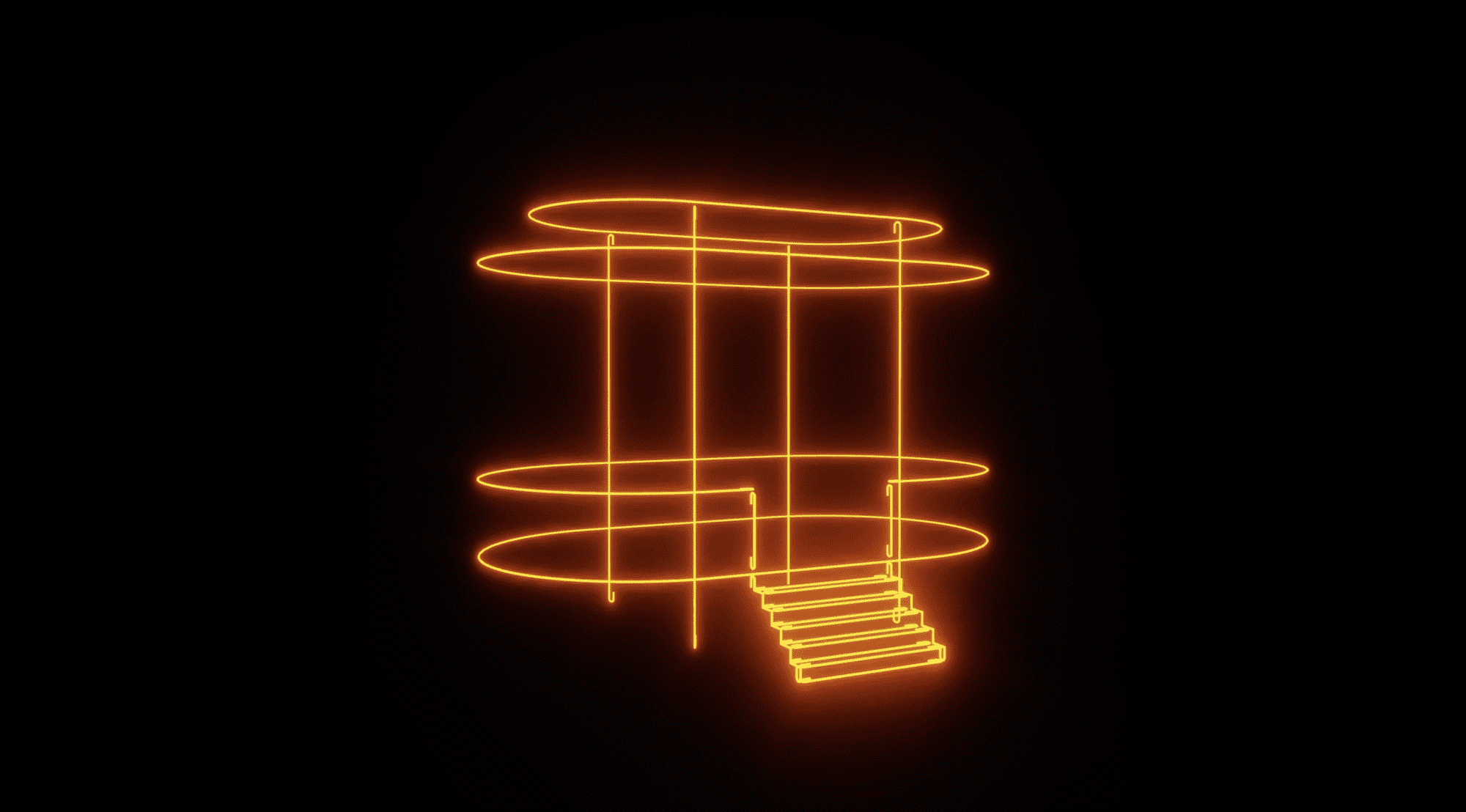

A year on from that first installation, he has brought this rich history into the digital realm by extending the artwork as non-fungible tokens (NFTs). In collaboration with artists Alina Nazmeeva, Kong Siden, and Prak Dalin, Lyno teamed up with screensguru, a Hong Kong-based intellectual property rights management platform and marketplace for fine art NFTs, to “drop” three iterations of Sala Samnak, each including an augmented reality IG filter and a single-channel video that anyone with $200 USD to spend can buy.

This drop is unique, not only for the cultural implications of representing a centuries-old practice as NFTs but also because the proceeds go toward Sa Sa Art Projects’ Pisaot Artist Residency Programme — making it an experiment with a new model of arts funding. Pisaot is an experimental arts residency for Cambodian and visiting artists. It’s hosted by the arts space Sa Sa Art Projects, which Lyno co-founded in 2010.

According to Ip Wai Lung, Chief Innovative Officer at screensguru, “charity drives with NFTs can be a new way to help art organisations… raise funds.” He added, “it is very important for an artist to have an independent and sustainable career… We help facilitate that by… [defining] ownership of their artworks in the intellectual property context.”

In the conversation that follows, Lyno informs me about some of his scepticism around the NFT market, this first step into digital art, and his aspirations to see how he can enable digital spaces as places of refuge. What stood out to me most is how intentionally he used generosity to tie it all together.

Noting the pitfalls of market logic, he says, “selling art is selling art for monetary value”. Rather than let that limit his horizons, he seeks to find ways to enrich society despite the “polluted” capitalist framework through which his work moves. That emphasis on intentionality and asking, “what can this do?” is an empowering sentiment that can resonate across sectors.

Could you tell me how Sala Samnak has been extended into a digital work?

screensguru asked if I would be interested in trying out the NFT market. I knew a bit about it but not deeply and saw this as an opportunity to explore. At first, the idea for the sales to come back to me felt awkward. However, because of Sala Samnak’s themes of collective generosity, it soon came to me to connect the sales with fundraising for the Pisaot Artists Residency.

The residency offers space, time, and resources to visiting artists. It’s a really fitting purpose so, it’s this idea of offering generosity that ties it together.

What were some of the apprehensions or questions you had about the NFT format and how did you overcome them?

I still have scepticism about cryptocurrency and how the NFT market, to be honest, is nothing remarkably different from the real art market. It seems polluted and has big players like the traditional art market.

Though, it could be something great because it offers more independence to artists. For example, you can enforce a system where for every second sale, or something similar, a portion of that sale will come back to the artist.

This means more economic sustainability for artists too, not just art dealers. However, it’s still a capitalist system. This weighs on me but selling art is selling art for monetary value. In contrast, I consider the sale of my NFT as fundraising — at least, it’s to support the residency at Sa Sa. That’s how I overcame my dilemma.

In addition to a first for you as an artist, how is this foray into NFTs an experiment for a new model of arts funding?

In one way, it could lead to no longer having to rely on the so-called big art collectors. We can make buying art more accessible to larger groups of people. For example, Sala Samnak, as a physical work, isn’t cheap to collect. It’s very fragile with a complicated technical system that requires a lot of maintenance and care. In the NFT form, this isn’t an issue, and I can make a lot more editions.

Hopefully, the affordable price will increase access to art collecting. There’s a big potential for funding through NFTs. But education and understanding among the wider public are needed. There are also issues about hacking, I saw an article about a wallet that disappeared in one night.

NFT art has the potential to allow a larger population to purchase works and support the arts. Hopefully, we can continue to think that way, specifically for Cambodia. We don’t have a lot of millionaires or billionaires buying art but have many art lovers.

A few weeks on from the drop, what are some of your early reflections on this experience both as an artist and co-founder of Sa Sa Art Projects?

To be honest, this is new and nobody on my team has experience with it. That’s why I said, “let’s try (this) with my work first.” It’s for the unique purpose of supporting the residency. So, I thought I could be the guinea pig. My team is very aware of this and supportive. screensguru is also new. We’re not rushing into anything but still trying to see how it works.

With the physical version of Sala Samnak created during the pandemic, you were already rethinking notions of intimacy. How have you carried that idea into the NFT versions?

I want to step back to the physical work at MIRAGE. The placement of the artwork, at the front of the gallery next to two glass windows on both sides, was very intentional. With the pandemic, we didn’t know if MIRAGE would open or close.

With Sala Samnak in the window, it was purposefully exposed to the street. People could experience it from outside the gallery, yet they still had the option to come in. That idea of combining the interior and exterior, private and public, and bringing the experiences together was something I wanted to keep thinking about.

With the NFT, I didn’t want to replicate that physical experience but produce a different experience that you couldn’t get in the gallery space. When you try to replicate the experience of the physical work digitally, the digital version becomes secondary and collapses.

Augmented reality comes into being through mobile devices. When Sala Samnak is in a digital form, you can take the structure and move it or zoom in. In this case, you can place it wherever you want. It’s something I want to explore more. I’m not sure if it’s more or less intimate. It’s a different form of interaction.

The original artwork is an engagement with the fading relevance of Sala Samnak in Cambodian society. Has your own reading of the work changed now that it exists as virtual space?

I was considering how people come together through digital space and if there is any way to think about how digital forms can be a place of refuge. If so, what kind of refuge? What does it do and affect?

I thought about how people are escaping Burma and Hong Kong. What are refuge and space for those communities? What is the role of the digital realm and what can it do? I don’t have the answers and my work hasn’t responded to that, but these were the questions I was thinking about.

In a panel hosted by screensguru, I heard you speak about how you attempt to enable inclusive, non-hierarchical spaces founded in sharing values, empathy, and places where we can learn to be human with the understanding of non-human coexistence. Could you expand on the non-human? Does that relate to the virtual?

The non-human aspect came into my consciousness through my House – Spirit project from the White Building. With the residents’ consent, comments, and collaboration, I collected more than one hundred spirit houses as they were moving out from the neighbourhood.

That project taught me so much about the cultural sphere, spiritual practice, and art-making. How cultural objects move and become art objects is not an easy process. As I adapted the cultural objects into art objects, I was aware of the responsibility I had to take for my decisions and the consequences.

Subsequently, visiting artists who stayed at Sa Sa Art Projects during their Pisaot residency reported they felt the presence of spirits and were haunted. I was advised to have a monk mediate a peace-making session. Respecting the traditions and rituals inherent in House – Spirit is now a part of the installation guide for the museum that collected the work. So, even though these spirit houses are now housed at a museum as artworks, they still carry the values and implications of cultural objects that require respect for the non-human.

Regarding the virtual, the question “is this real?” is not so interesting to me. If this isn’t real, why does it have an impact on our lived experiences? For me, it’s more about what does this do? It creates a lived reality. Thinking about the virtual in relation to Sala Samnak, I wonder where people can come together and seek refuge, and what does this mean?

I’m just now experiencing and learning from that form. And hopefully, with this first step, I can learn more and see what kind of community can form and exist in this virtual space.

____________________________________

Vuth Lyno’s work was most recently exhibited at Master of Lands and Waters at Sa Sa Art Projects, which ran until 31 March 2022. He is also currently taking part in the SEA AiR residency.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.