….is for Orientalism.

I come from a land, from a faraway land where the caravan camels roam.

Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face.

It’s barbaric, but hey it’s home.

Do these song lyrics sound familiar… but not quite?

If so, you probably have in mind the altered version of the tune Arabian Nights from Disney’s Aladdin, which describes miles of sun-scorched desert, instead of bloodthirsty, scimitar-wielding Arabs.

While Disney eventually corrected these troubling lyrics, popular culture remains full of negative stereotypes of the ‘Orient’ — a generic term that flattens regions as diverse as West Asia, South Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. The Indiana Jones series, Katy Perry’s music video for the song Dark Horse, and Marvel’s Doctor Strange — these are just a few examples of what we might call ‘Orientalism.’

As a critical concept, ‘Orientalism’ was first popularised by Edward Said, a Palestinian American professor who found that Western representations of the Arab world were vastly different from his own experiences growing up in Cairo and Jerusalem.

Simply put, Orientalism refers to a pattern of thought that presents the Orient as a negative mirror-image of the Occident.

It asserts that whatever the West is not, the East is. If the West is civilised, rational, scientific, and progressive, then the East must be uncivilised, irrational, sensual, and rooted in a timeless primitive past.

Orientalism in 19th Century European Painting

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer is a textbook example of Orientalism in 19th-century European painting:

But who exactly is this snake charmer? Even though he stands as the focal point of the composition, Gérôme deliberately hides the boy’s face from us. As Linda Nochlin points out in The Imaginary Orient, the boy’s obscured genitals are an “insistent, sexually charged mystery” that “signifies a more general one: the mystery of the East itself”.

The calligraphy on the walls — inscrutable to the painting’s intended, European audience — only intensifies the mystique of snake-charming and its associations with “magic” and “tradition.”

Another detail you might’ve noticed is the faded and chipped wall tiles to the left of the work. Gérôme deliberately freezes this ‘exotic’ scene in the distant past — a timeless, ahistorical realm left behind by progress and development.

These ideas about the East are made all the more convincing by Gérôme’s realistic style. By concealing their brushstrokes, Orientalist painters convinced their audiences that they were seeing ‘the real thing’ — and not a picture mediated by a European artist, who was perhaps present at the scene as a colonialist or tourist. This allowed such painters to evade the less-than-savoury circumstances in which these representations were made.

In Said’s words, “The scientist, the scholar, the missionary, the trader, or the soldier was in, or thought about, the Orient because he could be there, or could think about it, with very little resistance on the Orient’s part.” (emphasis added).

Orientalism in 19th Century Southeast Asian Art

While Orientalism is based on Eurocentric assumptions, there are also non-European artists whose works fall within this category. Arab-Javanese painter Raden Saleh is a fascinating case study of an ‘Oriental’ seeing himself through the eyes of the Occident.

Born in the Dutch East Indies, Raden Saleh excelled in the academic tradition, finding favour across Europe’s elite circles, where he was renowned for his portraits, landscapes, and animal hunt paintings.

In Perburuan Banteng, Raden Saleh paints warriors with batik clothing, turbans, and straw hats battling a wild bull against a sunlit tropical landscape. But despite these markers of ‘Javanese-ness,’ Raden Saleh relies on the same visual tropes that we see in Eugène Delacroix and Horace Vernet’s Orientalist paintings below, where man and beast mingle in a tableau of apparent exoticism and savagery.

As with Gérôme, Ingres, Delacroix, and Vernet’s paintings, Banteng Hunt is extraordinarily detailed. Every hair of the lion’s mane, every blade of grass, and every drop of blood is rendered with precision, creating an impression of documentary reality.

Yet, this dramatic scene is obviously constructed.

Although we might expect Raden Saleh to portray the Orient more authentically given his Arab-Javanese heritage, his art is no less Orientalist than that of his European peers. To recognise this isn’t to criticise Raden Saleh, but to acknowledge how an artist from the colonies could only gain recognition in Europe by ‘sticking to the rules of the game.’

By mastering the dynamics of light, shade, proportion, and three-dimensionality, Raden Saleh proved that he, an ‘Oriental,’ was of the same calibre as the best European artists. (If you’re interested, you can find out more about Saleh here)

Contemporary Art Against Orientalism

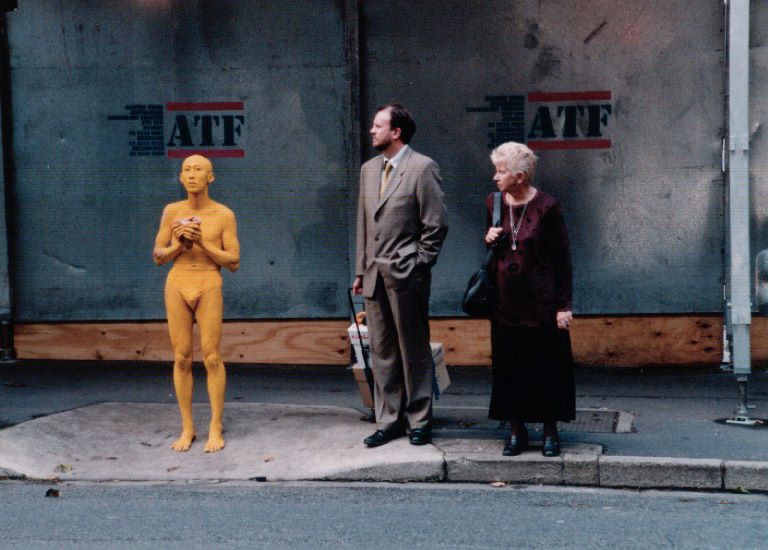

Looking back from a postcolonial world, artists today have developed all sorts of strategies to unravel Orientalist stereotypes. Singaporean artist Lee Wen’s performance series Journey of a Yellow Man (1992-2012) confronts the racialisation of East Asians, who, in Western eyes may be defined solely by their ‘yellowness.’

The series grew out of the artist’s experiences of ethnic and cultural discrimination as an art student in London, where he was constantly mistaken for a Chinese national. Lee’s work also speaks to the history of the ‘Yellow Peril’ — a xenophobic stereotype that justified European attempts to colonise China, while fuelling discriminatory policies against the dangerous, cunning, and “filthy yellow hordes” who immigrated to the West.

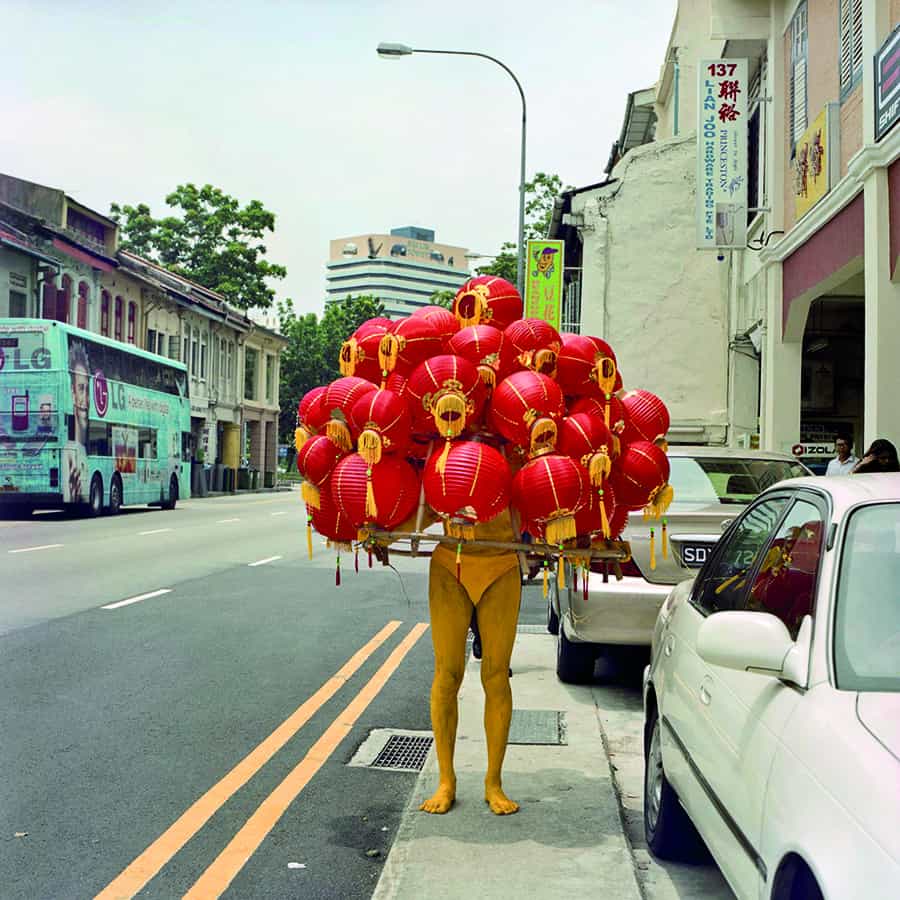

In his work Strange Fruit (2003), Lee Wen covered his body entirely in yellow paint, shouldered a dome-like contraption made from red Chinese lanterns, and walked around Singapore. By amplifying these markers of Chinese cultural identity to the point of excess, Lee Wen parodied the trope of the ‘yellow’ East Asian, revealing its absurdity.

Works like Lee Wen’s challenge the assumption that cultural traits are innate, instead suggesting that they are like masks that we put on as we ‘perform’ ourselves to others. Lee Wen’s satirical performances reveal Orientalism’s static, binary view of East-West differences to be nothing but a farce.

A Conclusion?

Despite a growing awareness about issues associated with cultural misrepresentation, Orientalist tropes of the East as the West’s negative mirror-image still persist — in all sorts of permutations.

Techno-orientalism, for instance, represents Asia as futuristic and technologically-advanced but “in dire need of Western consciousness-raising” — think sci-fi cyberpunk movies and TV shows set in a dystopian city (usually a mix of Tokyo and Hong Kong, or Singapore as “Westworld”). Like Said’s Orientalism, this new version refuses to see the East as a place that exists on the same historical timeline as the West, portraying it as irredeemably alien.

Though such visual representations may seem harmless enough, we’ve seen how they can be heavily tangled up with politics and cultural oppression. As an analytical lens, the concept of Orientalism offers us the tools with which we might dismantle the enormous system of differences that places the Eastern Other in a perpetually inferior position.

There aren’t any easy solutions to the problem of cultural misrepresentation, but perhaps the first step lies in seeing what’s really at stake and understanding where these ideas originated from.

____________________________

Letter ‘O’ illustration by Nadra Ahmad