…is for Photography.

Before the era of digitisation, photography involved the creation of a permanent and tangible image on a surface through the manipulation of light and chemicals. This can be attributed to the French inventors Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and Louis Daguerre, as well as the British inventor Henry Fox Talbot in the mid-nineteenth century. Daguerre’s reputation has eclipsed the other two figures, even though his invention of the daguerrotype was only possible due to his collaborative partnership with Niepce and Talbot. Their catotype process was the rightful precursor to the later forms of photography that we are now familiar with.

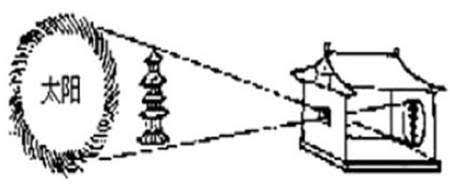

However, photography has a longer history than is usually expected as Chinese and Arab philosophers had observed the effect of the camera obscura by the first half of the second millennium. The camera obscura was a dark room with a small hole in the wall which allowed light to pass through it. An image from outside would appear on the wall opposite the hole, in a laterally and vertically inverted version.

Photography in Southeast Asia

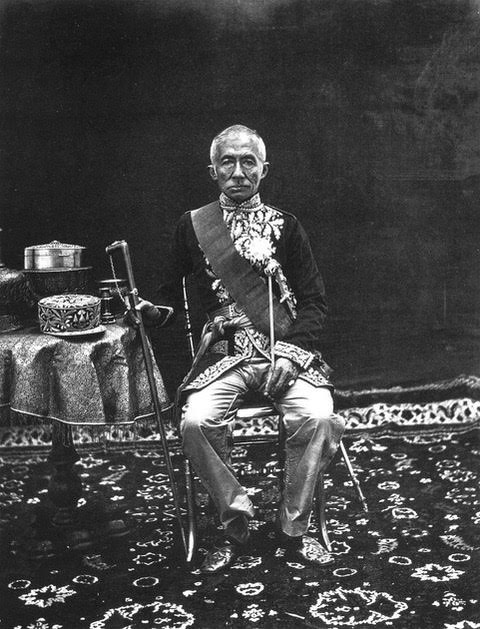

Local elites in Southeast Asia first came across photography in the nineteenth century through itinerant photographers from Europe, such as John Thomson and J. Newman. Some, such as Gustav Lambert, even set up studios in the region. Some photographers stopped over in Singapore, which was rich in photographic supplies, before continuing their journeys to other parts of the region.

Photography was also introduced to countries through their royal courts. For example, members of the Siamese royal court learnt how to use the daguerreotype camera when it was brought in by a French missionary.

A Worthy Art Form

Unlike mediums such as painting and sculpture, which have been practised for hundreds and thousands of years and are long-accepted within the art historical canon, practitioners of photography had to justify the medium as a compelling form of artistic expression in its early years. The medium’s dependence on machinery conflates the roles of man and machinery in the making of a photograph.

The debate on whether photography was worthy of being considered an art form rested on the extent to which man could be said to have decisively shaped the outcome of a photograph. Another concern was whether photography could be used to create works that were not merely a replica of reality but reflected the colourful subjectivity of the practitioner’s eye.

Photography in Contemporary Art

What a View of the Penang Bridge… And with the Haze as Well (1997) is a work by the Malaysian artist Ismail Hashim. It consists of an assemblage of photographs formed by grids, collectively depicting the Penang Bridge and its dirty environs. However, if we only look at the top row, we see a picturesque, almost ethereal image of a pristine beach. Photographs, though realistic, cannot wholly capture all the nuances of reality, because the images we see, and thus the truth that they claim to represent, depend on how the photographer in question frames the composition.

In The Scroll of Thich Quang Duc, The Scroll of the Women and Children of Mai Lai and The Scroll of Phan Thi Kim Phuc, all made in 2013, Vietnamese American artist Dinh Q. Lê distorted and elongated notorious photographs of the Vietnam War. These photographs shocked viewers about the horrors of the war when they were first published. However, over time, even the most violent images lose their potency when they become too familiar.

The works seem to resemble scroll paintings but also have sculptural qualities, with their folds and creases. In this work, the artist has rendered the images completely unrecognizable as photographs. Nonetheless, the incongruous and accentuated colours of the pictures effectively evoke the frenzied and incomprehensible emotional, mental, and physical traumas that the war inflicted on its victims.

Neal Oshima, though ethnically Japanese and born in New York, spent much of his career photographing subjects and objects in the Philippines. Untitled (2000) is a photogram of a traditional shirt, made of natural fibres from plants like banana and pineapple, widely worn by Filipino women before the American colonisation of the region in the nineteenth century. The print is produced with light-sensitive paper without a camera and captures the actual scale of the shirt together with its wear and tear, therefore imprinting the paper with distinctive traces of its wearer.

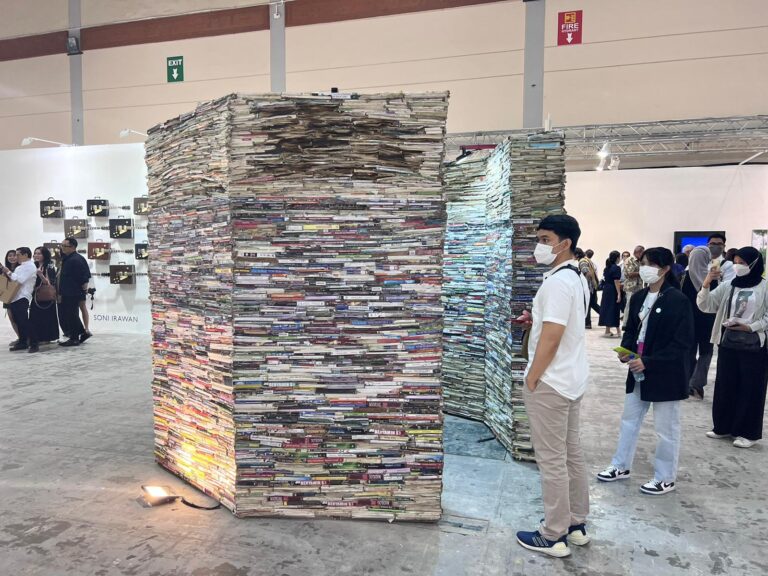

Like any other medium, artists created photographic works to conduct visual experiments, address sociopolitical issues, and record the vibrant worlds of their inner and outer lives. Today, the boundaries between amateur, journalistic, and fine-art photography continue to be contested as their techniques and aesthetics sometimes overlap. Artists also use photographs in collages and mixed media installations, which combine various materials and mediums, thus testing the practical and conceptual limits of photography.

________________________________

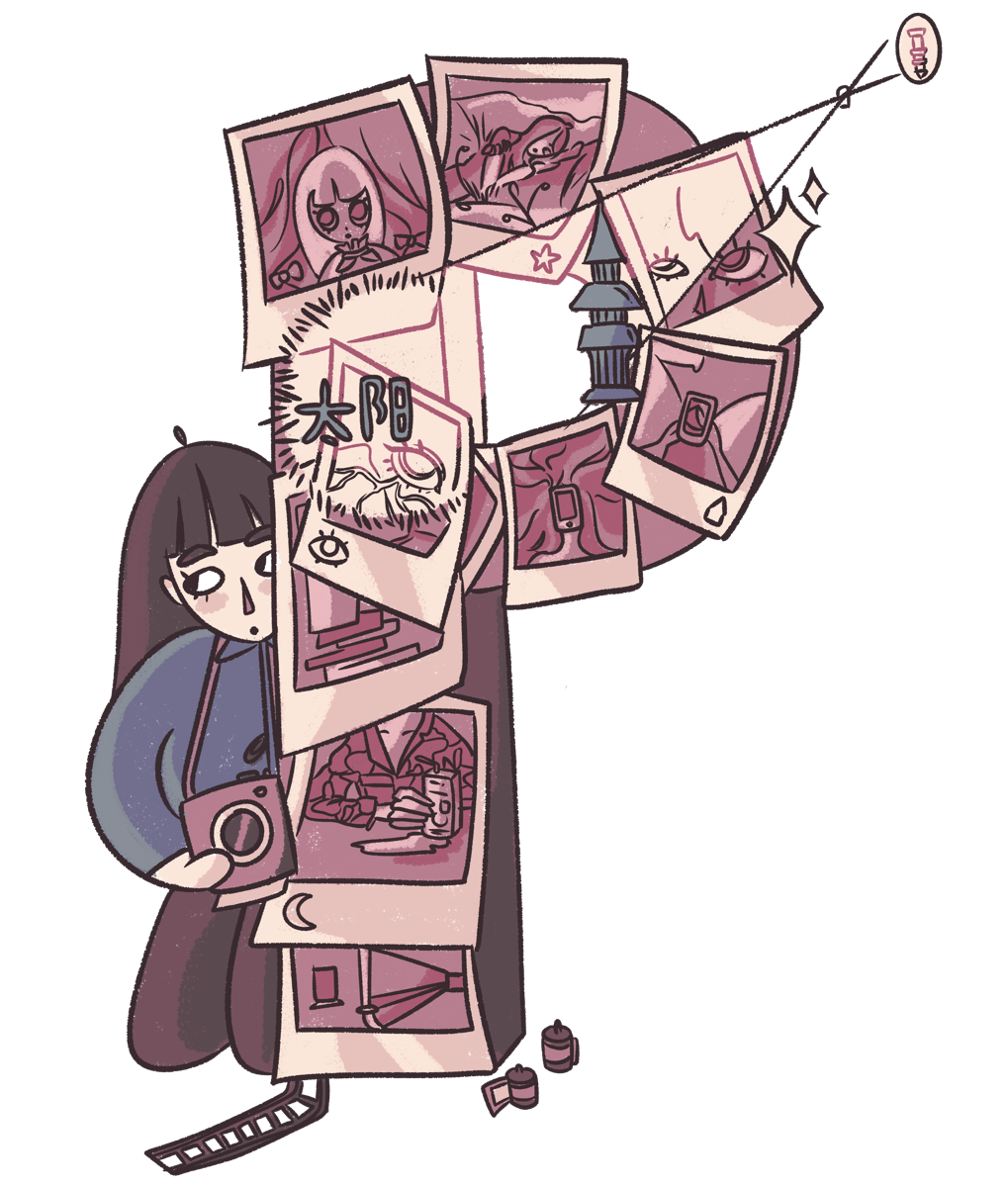

Letter ‘P’ illustration by Nadra Ahmad