Picture the Singaporean skyline in your mind’s eye and you will see endless glass surfaces and futuristic blockbuster skyscrapers designed by internationally known architects: modern, progressive, and fantastical.

Put that image out of your mind for now, as the buildings featured in UNIT., are notable for their everyday nature.

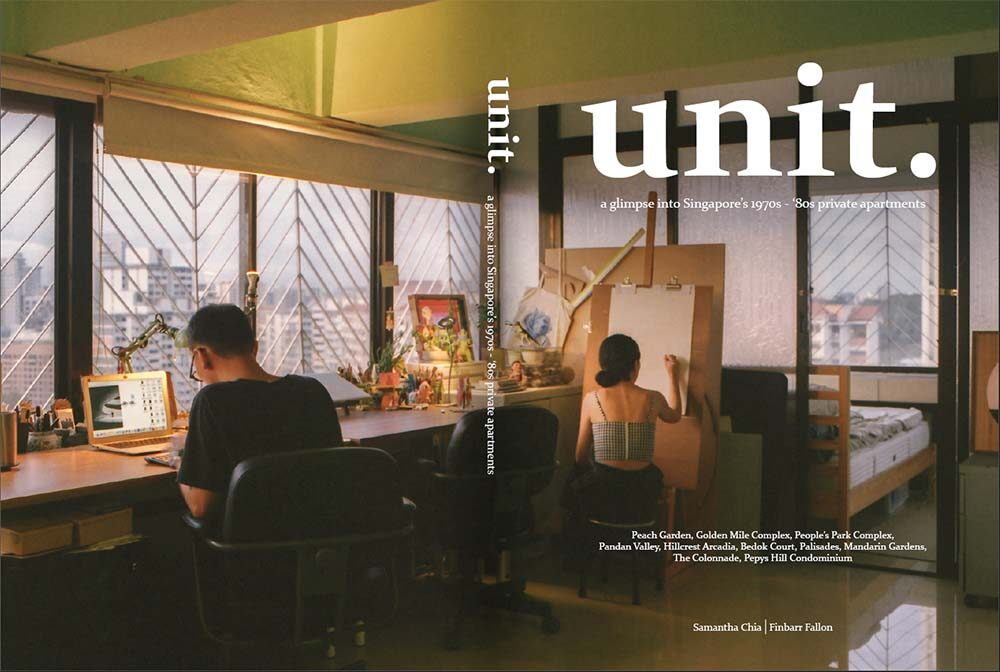

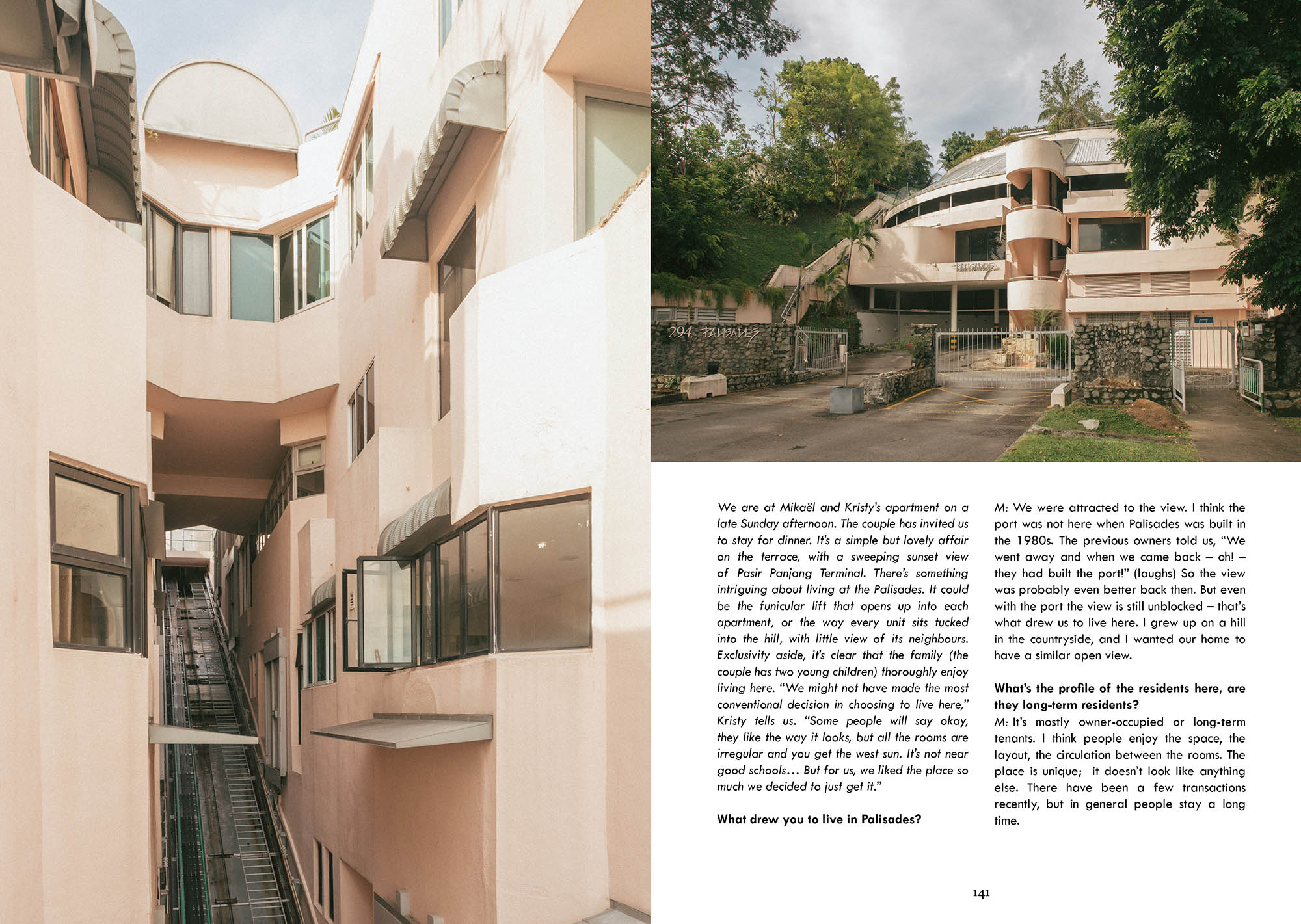

This project by architectural photographer Finbarr Fallon and urban planner Samantha Chia covers private apartments built in Singapore between the 1970s and ‘80s, through the eyes of the people living in them.

Photographs of the apartments and interviews with the residents capture a glimpse into their home lives. While some of the residents featured have spent a lifetime in their spaces, others are transitory custodians of their spaces.

Ahead of their ongoing exhibition at HEARTH by Art Outreach, I chat to the duo about Singaporean architecture, apartment living, and our relationships with our homes.

Us and our spaces

Architects work with space as their medium, in the same way that sculptors work with stone or clay. Wherever you are right now is a space that an architect has thoughtfully crafted for you, from the layout and placement of walls, to the materials used on every surface.

The touch of an architect is extensive, especially in a dense urban environment like ours.

Samantha shared that for the average Singaporean, our most significant relationship with architecture takes place while designing our first apartment and influencing the shape and feel of the spaces we choose to live in.

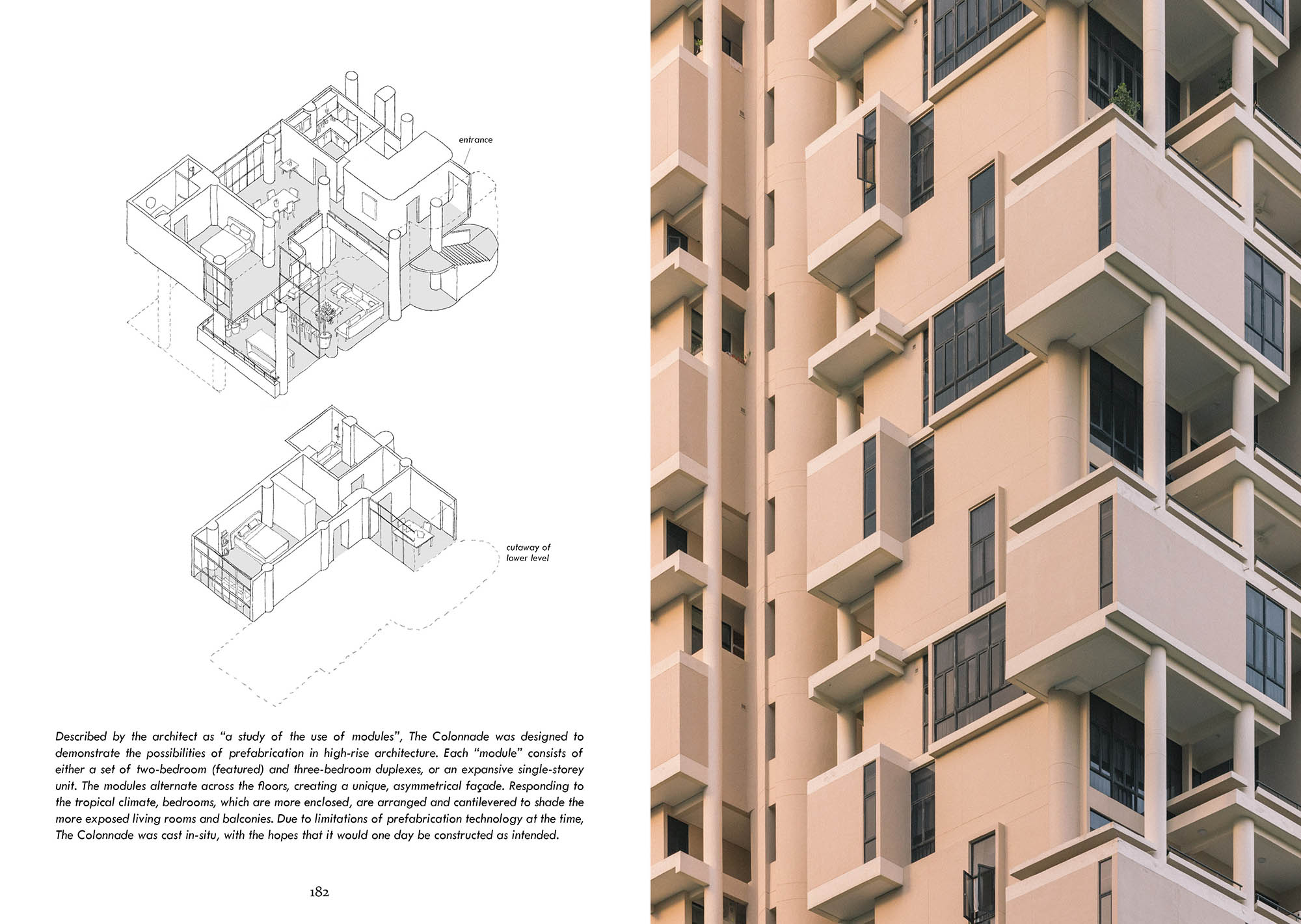

If you’ve chosen to live in newer developments, you might have noticed that there are many limitations to what you can change about your space. Such apartments, created through prefabricated construction, are cheaper to create and faster to build.

The homes in UNIT. represent an earlier and significantly different era in building development, one where creativity was of more urgency than profitability.

Terraces in the sky

Post-independence, the 1970s-1980s saw Singapore struggle to figure out a new way of living. As the population density rose rapidly, there was an urgent push towards high-rise living.

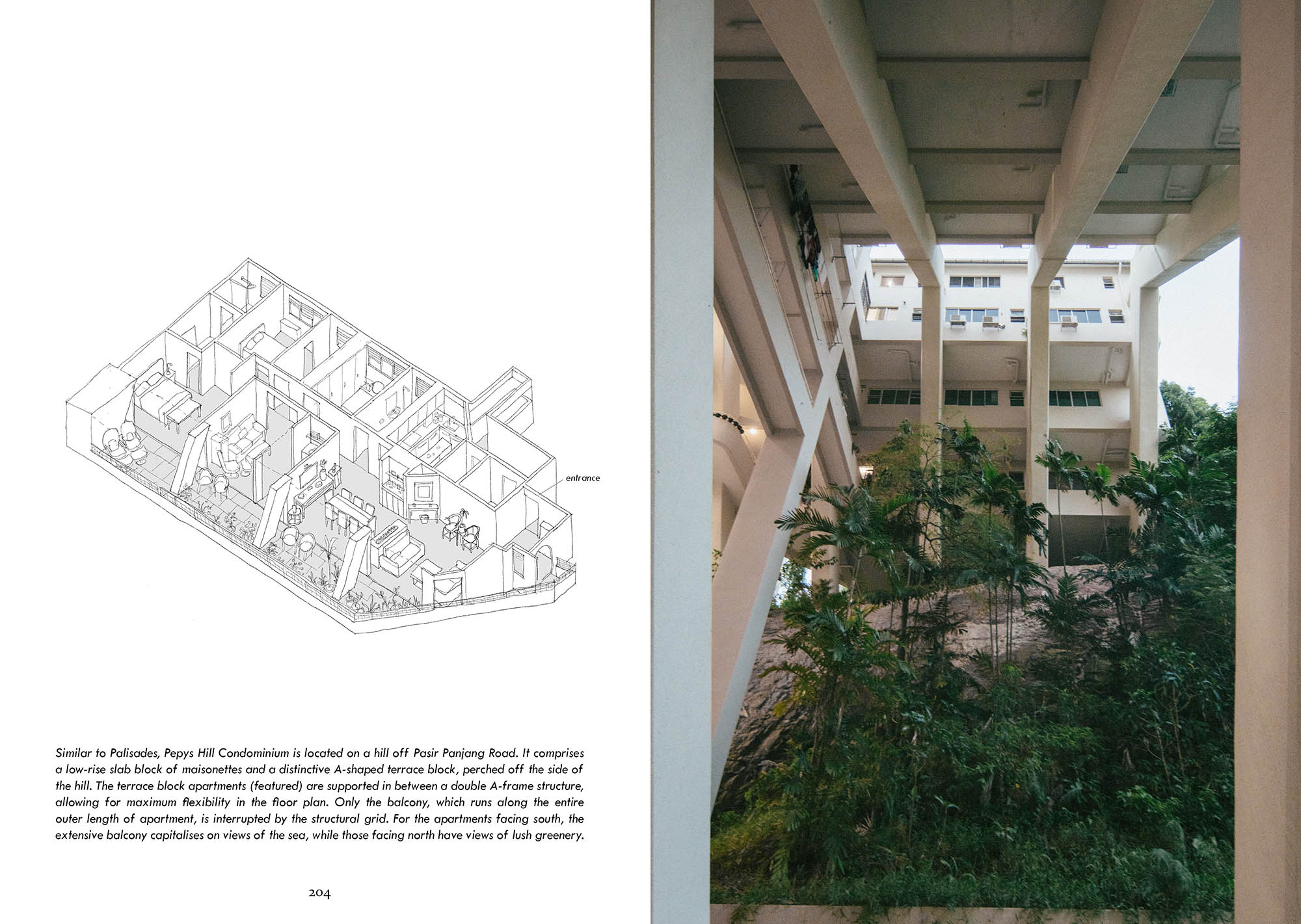

Private developments seeking to attract the middle and upper classes faced a more pressing challenge than public housing. Architects had to find innovative solutions, such as balconies and double-storey units, that would compel these people to choose apartment life over the conventional luxuries of landed living.

As a result, these developments had to be more than just an apartment; Bedok Court in particular was marketed as “landed living in the sky”, promising the best of both worlds.

As apartment living has become the norm in cities worldwide, such quirks and unusual features have faded away, leaving this collection of buildings to become a unique landmark in the history of urban development.

Architecting spaces and lives

With such a compelling collection of buildings, why focus on the residents within, and not the architects?

Samantha explained that:

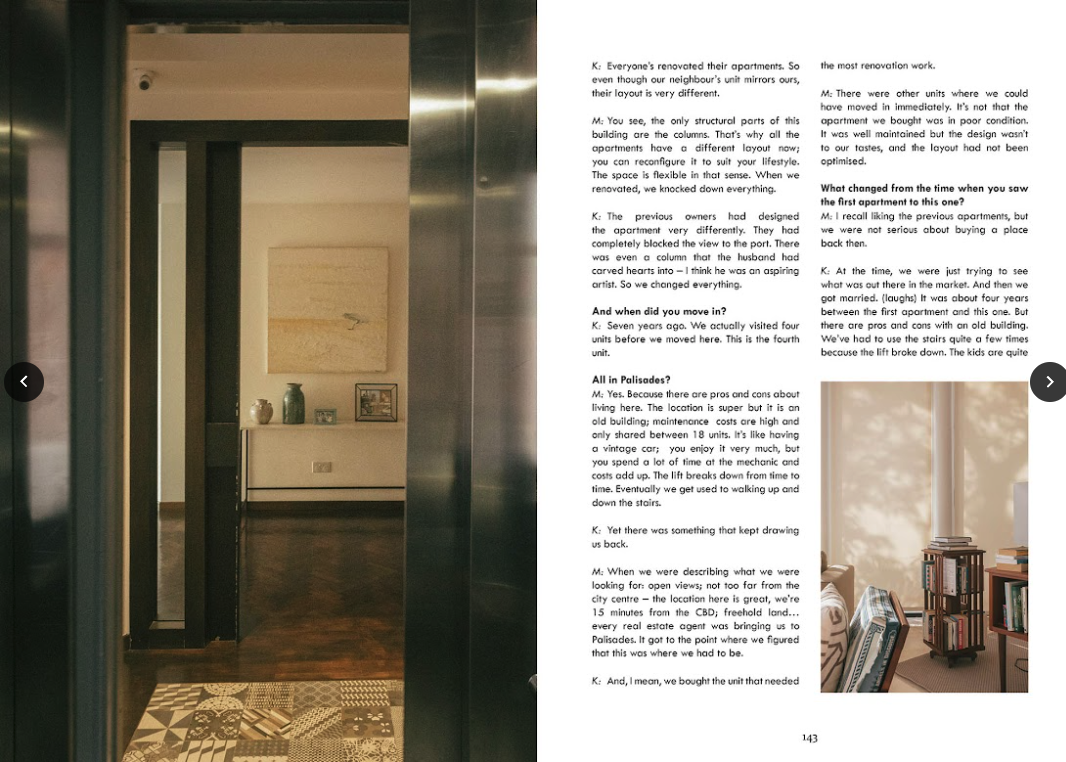

“We often read or hear about the architect’s design intention, but we don’t often get the resident’s perspective of what it’s like to live in these buildings.”

Although the residents come from different backgrounds and demographics, what they share is an appreciation for the uniqueness of their spaces. Despite not being designers themselves, they recognise how the design of their space improves their lives.

Some have lived in their homes for a long time and carried out renovations to shift walls and structures. Others, especially the younger residents, architect their lives and lifestyles, creating new ways of living around their distinct spaces.

What it means to live in a home

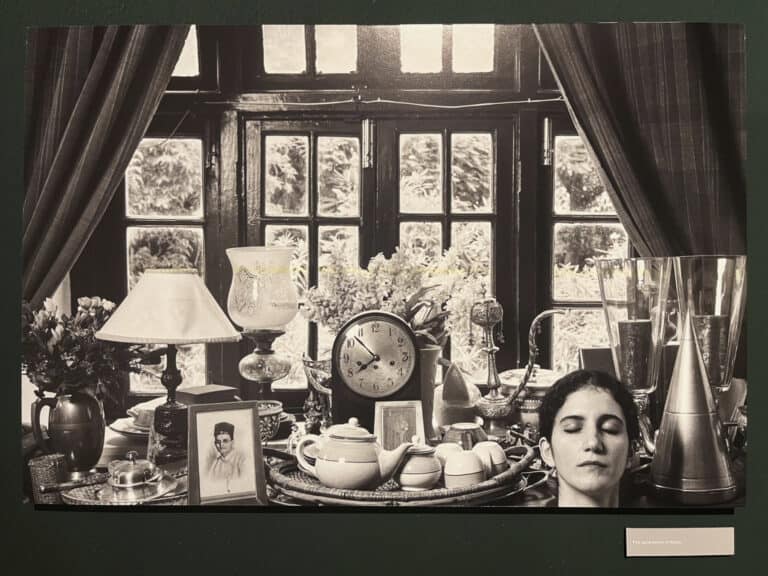

Although I had found the exteriors of some of the buildings recognisable, their interiors were almost always surprising.

One example was Golden Mile Complex, which I had always envisioned as blocky and dim when passing by. Instead, the interior that Finbarr photographed was warm and homely. Light streams in from large windows and illuminates a restrained collection of home furnishings.

The photos could easily be depictions of luxury and desire, given how expensive some of the units are (a 4-bedroom at Pandan Valley could cost you up to SGD $4mil).

However, Finbarr’s photos have a way of capturing the imperfect, delicately balancing the geometry and logic of the spaces with the distinctive ways in which people live their lives. Instead of yearning to live there, you find yourself wanting to get to know the people within.

Between the past and future

You might think that this is a project about conservation, given that these forty- to fifty-year-old flats are ripe for the en bloc process or conservation by the government.

Samantha and Finbarr, however, do not believe that it’s a book about conservation. Samantha says:

“The book isn’t about advocating a certain perspective, but documenting a lived experience.”

“Most of the people are quite pragmatic,” says Finbarr. The residents are keenly aware of the maintenance problems that older buildings face and understand that their tenure in their spaces is not a permanent one.

Sidestepping nostalgia, speculation, or advocacy, the project instead captures a moment in the residents’ lives.

Between history and photography

As UNIT. is a collaborative project by two architects whose work is tangential to building design, I was curious about how this project has responded to and shaped their respective practices.

Samantha’s projects have often unfolded around untold narratives that shape the history and urban design of Singapore. Her interest in the memory of spaces shows in the way she conducts the interviews, nudging the residents to peel back the layers of their relationship with their spaces.

Finbarr’s photography responds to the conversations, in turn, bringing the audience in not as a voyeur, but as a guest, wandering around the stories and spaces.

As an architectural photographer, he usually photographs spaces that are deliberately staged and “tidied up” for the viewer. This project was a rare chance for him to do the opposite, as the duo encouraged the residents to leave their spaces untouched.

Emerging connections

When they started the project in 2020, Samantha and Finbarr had worried about not being able to find people willing to open up their homes and lives.

But as word of the project spread, they were able to get in contact with people who are very generous and “house proud”. One such pair was the residents at the Palisades, who even hosted them for a dinner and put them in contact with friends living in the other developments.

Within a week of release, the publication had racked up hundreds of pre-orders. When asked about this, Samantha and Finbarr expressed their surprise and gratitude towards the interest. Finbarr said, “at the time, we weren’t sure whether anyone would even be interested to hear about the lives of other people.”

They hypothesise that the wave of interest is driven by a younger generation of Singaporeans who are more appreciative of design and who want to connect to national history through architecture.

A fascination with home life

Finbarr shared that one of the major challenges of the project was arranging conversations with the residents and visiting them in their homes. Ever-changing COVID-19 regulations meant that some interviews took more than a few attempts to arrange.

When the interviews did happen, however, they were contemplative, as though the residents’ relationships with their homes had deepened through being confined in them.

This is a unique quality of pandemic projects — the significant logistical challenges to be overcome, and the resulting sense of perspective and reflectiveness.

Apartment living is currently at an inflection point. We’ve become used to our apartments being not just places to live, but also a financial investment and a ritual of adulthood. And through the last few years, they’ve also become our offices, gyms, and modes of self-expression.

UNIT. encourages us to examine our own relationships with our homes, and investigate what it means to feel at home.

Where to, next?

While the project started as a publication, the ongoing exhibition at Art Outreach places more attention on the photographs. Samantha and Finbarr have also talked about other forms of the project in the future, such as making a film.

My personal experience is that this project’s true form lies in the way my relationship with space changed after speaking to Samantha and Finbarr.

As I turned off my camera to end our call, I turned around to face the flat in which I have lived the past few years and discovered new details — the crookedness of walls, the awkwardness of spaces behind doors, and the imprints of my life.

I suddenly recall something Samantha said, “if everything has to go, you should understand what it is that you’re taking away.” I think about the time remaining on my government-enforced lease, and how my space has defined my adult life and relationships.

In Singapore, our living spaces frame our lives, but only for a unit of time.

____________________________________

UNIT. runs at Art Outreach Singapore till 31 July 2022. More details can be found here.