A hand-drawn map of Kampong Gelam, a mid-20th century bird-shaped congkak set, Raden Saleh’s magnificent Horse Attacked By Lion, and an embroidered selendang (shoulder cloth) that once belonged to Singapore’s former First Lady, Puan Noor Aishah — what do these objects have in common?

Well, these are just some of the objects on display at the Malay Heritage Centre’s mammoth exhibition Cerita. The title comes from the Malay word for ‘stories’.

Focused on foregrounding “the stories and narratives of life in the Nusantara (Malay Archipelago),” the exhibition is a treasure trove of eighty objects and artworks representing the nuances, interconnectedness, and impact of the Nusantara communities in Singapore.

The showcase includes new artefacts alongside highlights from previous exhibitions, all of which were collected in the past decade. The exhibition’s run has been extended till 30 October 2022, before the Centre closes for renovations.

The exhibition begins outdoors, in the garden.

While the Centre has an ethnographic focus, Cerita boasts notable artworks alongside the objects on display — thanks to its guest curator Syed Muhammad Hafiz. Khairulddin Wahab’s sprawling work Words in the Winds is the first one to greet you. Inspired by some of the exhibition’s objects, the vibrant, psychedelic painting depicts a storyteller narrating stories from the Sulalatus Salatin (Malay Annals) and the Nusantara.

The exhibition’s first section Kita touches on the “collective experiences of the historic Kampong Gelam,” while highlighting the dynamic exchange of culture between Singapore’s Malay communities and the wider Nusantara. Some fascinating objects you might catch a glimpse of include a stunningly intricate Pawukon (Javanese calendrical manuscript); a twentieth-century congkak set with a bird motif; and even an elaborately carved ceremonial circumcision chair, which was used by kraton (palace) nobility in Yogyakarta.

Art enthusiasts will also be delighted to spot the works of seminal artists in the second gallery Meraka, which focuses on craft and visual culture. Expect to see a stoneware pot by Cultural Medallion recipient Iskander Jalil, Jaafar Latiff’s mixed media ink work Unspoken Dialogue, and Sarkasi Said’s batik piece Untitled (Shahadah) in dialogue with one another. With Latiff and Said incorporating visual references to their religion in their practices, Hafiz tells me that they were grouped together to start a conversation around the nuances and perceptions of Islamic art.

Besides the rabbit hole of stories that the exhibition showcased, what struck me was the distinct lack of wall text. As an art historian who’s used to fixating on facts and context, this almost frightened me.

However, I soon found that this presentation gave me the freedom to focus primarily on the objects on display, rather than feeling as if I had to absorb mounds of text before I could admire them.

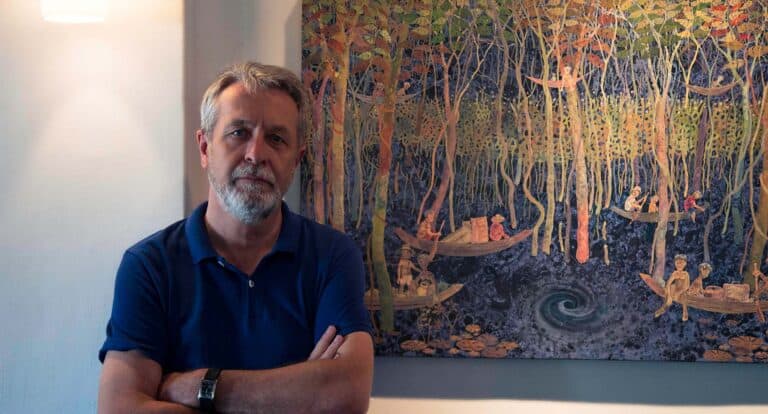

And this was a purposeful curatorial decision by Hafiz, to encourage visitors to reflect on the objects and what they might mean to them. Intrigued by this direction, I spoke to Hafiz in more depth.

Cerita is meant to celebrate the past decade of exhibitions at the Malay Heritage Centre (MHC). It’s a big time period — how did you even begin narrowing it down?

Yes, you’re right about the time period. But it is also about the various narratives that were [highlighted] by the respective exhibitions over the decade – each with its own contexts and motivations! My co-curator Zinnurain Nasir and I decided that we could never do justice [to the time period] if we were to select certain highlights or summarise a decade’s worth of exhibitions.

With Cerita, we hoped to capture the main impulse of the decade, which was ‘storytelling’. At its very core, MHC has been a repository of community stories and numerous narratives, which is why we thought [the exhibition title] Cerita [which means ‘stories’] was apt.

Seeing that you have a background in art history, what was it like shifting to curating a show on social history for an ethnographic museum?

That was the initial bait for me! Though I’ve been mostly associated with the art world, I’ve always seen or understood culture through a wider lens. I’ve always been fascinated by the world of objects and artefacts. In fact, it has always been an ambition of mine to curate an exhibition which includes artworks, objects and artefacts so you can say this is a natural shift for me!

Even though Cerita is mainly focused on social history, works by contemporary artist Khairulddin Wahab and seminal painter Radan Saleh still make an appearance. Can you speak more on including these artworks and how they add to the show’s dialogue?

For me, artworks have their own social histories and can [serve as] platforms to discuss them. It’s not as if these are separate elements – I just see them as another layer of the whole exhibition experience.

For Khairulddin’s work, it was his research into the close relationship between the Malay world and the natural world that made me select him. His work was meant to remind us of this relationship [and] we can see in [his painting] the motifs and patterns found within Malay craftsmanship.

As for Raden Saleh, one of the things about him that I’ve always felt hasn’t really been discussed is his role as not just an artist, but also as a cultural ambassador while residing in Europe. As he was operating within the elite social circles in 19th century Germany and the Netherlands, he would’ve been seen as both an anomaly and more importantly, as a representation of the ‘Far East’ or the ‘Oriental’.

Thinking about how he would’ve chosen to talk about Java and the craftsmanship and rich traditions of the Nusantara at the ‘height’ of colonialism, prompted my inclusion of his painting.

One of the first things visitors might notice in Cerita is the lack of exhibition text; a decision you made so visitors can focus on the objects on display. Can you speak more about that and how you hope visitors will reflect on their own experiences?

Reducing [the amount of] text was deliberate. First, we wanted to test this new strategy, which requires the audience to rely less on the curators’ ‘voices’. For the longest time, we have fed visitors a lot of information, which can be both good and bad. Some might devour [the text] and read every single word while some are not as dependent.

That was why we thought about selecting objects which, upon viewing, can immediately trigger a response or a ‘story’ from the viewers themselves.

Secondly, we also wanted the visitors to make the connections between the objects and themselves. As curators, sometimes we underestimate the audience or maybe in our enthusiasm, we get too excited to share our research.

We should give the audience the time and space to reflect and think about what they’re seeing. Especially since we’re slowly returning to the world of physical exhibitions, the [physical] ‘encounter’ with what’s on display should also be welcomed back.

Were they any objects whose stories surprised or intrigued you?

There’s been more than a few actually!

For example, the animal-shaped ingots [which served as currency from the 15th century onwards] interested me, because of how far financial transactions have developed in our society, especially with e-wallets these days. Maybe it’s because I still prefer cash?

The private loans have also [intrigued] me, especially [when] the lenders’ narratives inform the collected objects’ significance. There was one lender who lent us a few objects. Though they seemed unremarkable at first glance, the stories behind how they ended up in the collection were priceless.

One of the objects was the ubiquitous water receptacle that used to be quite commonplace in Malay weddings ten to fifteen years ago. Due to the practice of eating with our hands, these receptacles used to be household items that would be [used] during weddings. Most Malay households I know would own at least a set or two but these are slowly disappearing as weddings [offer] buffets or serve [dishes] with cutlery.

Besides being something from the past, this particular receptacle also had the name of the lender’s aunt on it. It ended up in the lender’s collection after she passed away, reminding us of the familial bond that existed in relation to the collective spirit of Malay weddings.

What do you hope visitors take away from Cerita, seeing that it’s MHC’s final show before its revamp?

Firstly, I hope that visitors will look forward to visiting MHC when it reopens in 2025 after the revamp. It’s a short break for us to calibrate and facilitate new research into our permanent galleries and special exhibitions series!

As for Cerita, I hope they are able to see some strategies that we are testing for future exhibitions at MHC. While it might not be the usual ‘packed’ show, we hope that there are still some favourites from the past exhibitions and some new [artefacts] from new lenders.

And since it’s going to be a while till our next special exhibition, I hope the public will come down to visit the exhibition in the current environment before the new, revamped MHC opens to the public in 2025! Travelling roadshows and pop-ups will definitely be part of the agenda [while MHC undergoes the revamp].

____________________________________

Cerita runs till 30 October 2022. Click here to learn more about it and visit the exhibition online here.