Kristine Tan’s a name that you might have come across in the past year if you have a particular interest in digital art.

Formerly the programmes manager for residencies at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore (NTU CCA Singapore), she’s also an independent curator whose interests lie at the intersection of contemporary art, science and technology.

As we hurtle towards the end of 2022, we caught up with her for a look back at some of her highlights this year.

Art and the internet

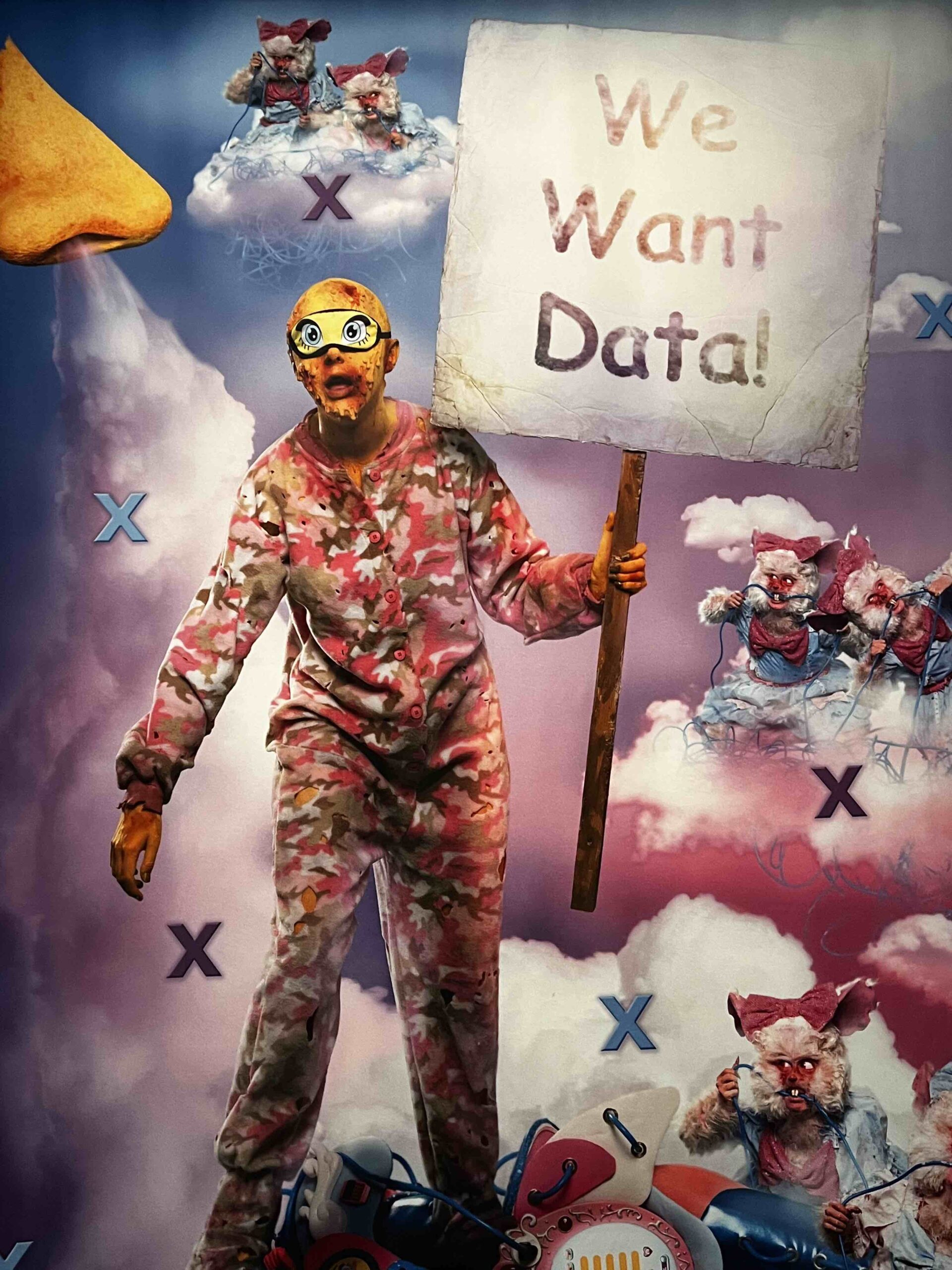

Information Wants To Be Free?: Art and The Internet, a presentation curated by Tan over March – May 2022, might have been one of the most interesting art shows this year, one which flew under the radar for many art lovers on account of its remote venue. Located in the far reaches of Boon Lay at the NTU ADM Gallery, part of a university campus as far removed from the artistic enclaves of Singapore as one can imagine, the show brought together artists who were both well-known locally as well as new foreign names.

Leveraging off her time spent in London while studying and researching for her postgraduate degree in curating at Goldsmith’s College, Tan was able to pull together a fascinating selection of artists and works which sought to spotlight the transition of the internet from early utopian ideas of a free global exchange of information, to a network that can unfortunately no longer claim to be democratic or neutral.

The works in the show featured contributing artists from Asia, Europe, the United Kingdom and the United States, and explored a range of contentious issues surrounding the role of Big Tech in the commercial exploitation of personal data, algorithmic bias, surveillance capitalism, and the compromised autonomy of users. Tan tells us that, to her knowledge, all works in the exhibition were displayed for the first time in Singapore — no mean feat for an exhibition of this size and scale. In a climate where digital art is often synonymous with NFTs and crypto investments, the show was also a breath of fresh air, moving beyond these common conceptions, and taking a probing conceptual look into works in all kinds of mediums.

Here’s a look at some of the pieces that went on display, if you missed them at the ADM Gallery:

Explains Tan, “I was reading the likes of Shoshana Zuboff, McKenzie Wark and Jaron Lanier who made comprehensive analyses of the fundamental problems with Web 2.0, and researching artists that investigated the socio-political economics of the internet. [The exhibition] was initially conceived of as a large-scale survey exhibition but was condensed for the ADM Gallery, focusing on works that examined the problematics of the online information economy that we are all reliant on. In Singapore, a tech-utopian narrative underpins our ‘Smart Nation’ and I really wanted to offer an alternative to this dominant ideology.”

Contextualised in the broader themes of the exhibition, the location of Information Wants To Be Free on a university campus — itself a bastion of information, knowledge and education — was perhaps a stroke of genius. Would students, immersed in the minutiae of day-to-day academic work, clutching onto their own precious electronic devices for dear life, be up for visiting an entire art exhibition dedicated to the ins and outs of electronic consumption and the internet age? Tan tells us that the galleries were beautiful and generous in size, but that she also had to “organise and lead tours for students and the general public ..[giving].. them the opportunity to find out more about the ideas and processes behind the exhibition.”

Musing on the more prosaic aspects of curation, Tan told us, “as an independent curator you often have to rely on institutional and/or governmental support to make your projects. Without the backing of ADM Gallery director Michelle Ho and NTU CCA Singapore who generously provided the majority of the equipment, this show would not have been possible.”

She offers these wise words to anyone considering a career in curating, “I think my advice to anyone who wants to organise or curate any sort of exhibition or art presentation is to not skimp on the communications! It is sometimes difficult to muster up the energy in the last leg when there isn’t a dedicated comms person to ensure the show gets the exposure it needs – but this is absolutely essential and shouldn’t be overlooked!”

Is everything for sale if the price is right?

NOT FOR SALE, a part of Singapore’s Art Week in January, was another expression of Tan’s interest in contemporary trends in digital art and media. This time, she turned her focus to consumerism and the idea of how it sometimes feels like everything is for sale. Teaming up with art Instagrammer and fellow cultural worker Gillian Daniel, under the moniker of proto projects, the duo sought to experiment with an expanded approach towards cultural production and exhibition-making, one that “provided unexpected entry points into the urgent issues of the now.”

The artwork commission funded by Singapore’s National Arts Council (NAC) invited artists Debbie Ding, Chong Yan Chuah and Yeyoon Avis Ann to create speculative video works that were screened on a digital billboard outside Fortune Centre and a new billboard at Kinex Mall.

With the display of works on prominent advertising billboards, the exhibition title itself – NOT FOR SALE – felt like a defiant statement against hyper-capitalism:

As part of the exhibition, members of the public were asked to respond to the following statement: “Tell us what is not for sale.”

Tan’s own response to the question was the rather cynical conclusion that “nothing is not for sale”.

She explains, “I guess this refers to the idea of ‘Capitalist Realism’ by Mark Fisher where it is hard to imagine an alternative to capitalism as we are so deeply entrenched [in] it. According to Fisher, “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism”.”

“The title of the project along with the presentation site of the advertising billboard was meant to be a provocation or thought experiment about what we think should be shielded from this system, as futile as that may prove to be,” she continues.

It was a show that prompted deep thought – one question that came to mind was how an exhibition like this might sit with notions of private art patronage. It is a reality of artistic production that artists need to be funded by the market, and the positioning of artworks as being unavailable for sale or “shielded” from unappealing consumerist notions, felt a little incongruent. While the works in NOT FOR SALE were not actually sold, artists were paid with funds from an NAC grant and Tan offers the view that “if there had been an interest in the video artworks, perhaps the artists would have sold them, as artists need to make money to sustain themselves!”

“We were not critiquing the art market in that way but I guess it was a way to consider the values that we hold important,” she explains.

The framing of NOT FOR SALE left us wondering whether general passersby were even aware of the works on display above them in the mess and chaos of the traffic and crowds around them. If you didn’t know where to look and at what time, you’d probably not even realise that you were in the presence of an art show. In turning everyday busy streets and buildings into art galleries of sorts, Tan and Daniel offered viewers an intriguing question — is art best enjoyed when one is so fully immersed in it that one fails to even recognise its very identity as ‘art?’ Or is such appreciation meaningless without a full exposition of the works and understanding of what one is looking at? Is there even room for meaningful aesthetic appreciation when an artwork is ensconced in such a commercial and consumerist environment?

Looking ahead

With two trailblazing exhibitions under her belt this year, we were curious about what’s next for this rising star. Tan tells us that she’s currently researching Southeast Asian artists for a show that she’s hoping to hold in London. Under the proto projects banner, Tan and Daniel are cooking up ideas exploring the relationship between food and society for an exhibition planned to take place in Singapore next year.

“Watch this space!” Tan urges us.

We don’t know about you, but we’re certainly sold.