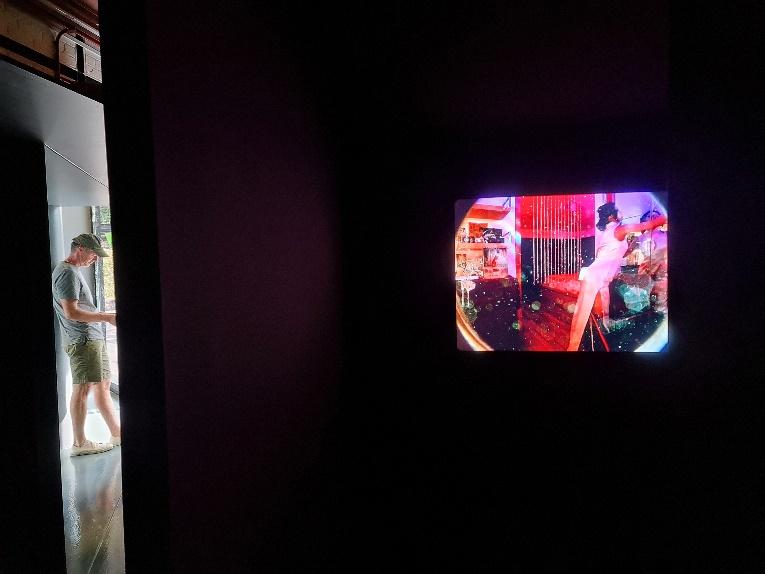

A mirrored walkway leads me into a darkened room, where I encounter sharp corners that force me to decide which turn to take. Where will this left turn lead me? Which turn should I make to follow that distant sound of a musical performance? How do I get to the glowing light in the far corner of the walkway, akin to a TV playing in the dark?

This is Dancing Without Touching, a solo exhibition by Singaporean artist Sarah Choo Jing, where she interprets movement and dance through the lens of Singapore’s 20th-century amusement parks. Choo chose this time period to offer a parallel between the bustling attractions and businesses that the entertainment world had brought to Singapore, and recent periods of social distancing and isolation.

Presented by Yeo Workshop in Gillman Barracks, the exhibition fills a dark room with ‘bespoke architectural armature’ arranged to create maze-like pathways that lead to various small video screens. This space was transformed in collaboration was space designers from HABIT.

With no clear route or specified direction, visitors are free to wander around to discover the video screens and distant musical sounds. As more visitors stroll in and explore the works, they also become markers of my journey within the installation–human markers for the wall I have passed and the pathways I have already walked.

At some point, it felt like I was in something like The Amazing Race, pit against every other audience member as we attempted to ‘clock in’ all the videos we were meant to watch. Each video screen was like a private performance by characters that might entertain you at a 20th-century amusement park: a cabaret girl, a boxer, a jester, a singer, and finally, a Chinese opera performer, all dressed up in their iconic costumes.

Amusement parks as alternate worlds

It has always been Choo’s signature to create seamlessly spliced images to fabricate painterly virtual realms for her characters, and this is also clear in the videos created for Dancing Without Touching.

The results are alternate realities that are otherworldly yet recognisable. This is noticeable in the environments each character inhabits—from the boxer’s locker room to the cabaret girl’s dressing room, making the characters in these realities familiar but distant at the same time.

The exhibition also presents a video sculpture, Only nearer than half a world apart, featuring a video wrapped around a cylindrical structure. Indicating the exhibition’s focus on 20th-century Singapore when the amusement parks New World, Great World, and Happy World existed, the video combines elements of past and present versions of these environments.

The video plays dazzling signage of those entertainment worlds layered over present-day Jalan Besar, and modern-day scenes of people waiting at bus stops. and construction scaffolding covering old shophouses.

Here, the artist reminds us of a time that once was; a time that has passed, yet still lingers.

A cast of characters

Moving through the installation feels uncanny, a reminder of a not-so-distant reality where we once had to dance without touching. Separated by literal walls and sectioned-out corners that could only accommodate a few at a time, the space evokes the social distancing we have become all too familiar with.

Every encased corner of the installation accommodated a group of three at most, allowing me to quietly observe the characters in the videos; characters that typically performed on loud, flashy stages in front of large crowds.

In the videos, the characters acted nonchalantly towards viewers, going about their business in their respective settings, unaware of the viewer’s gaze. On one of the screens, the cabaret girl rehearsed her dance moves in her dressing room, whilst observing her reflection in the mirror. On another, the boxer adjusted the grip tape on his hands in a locker room before practising on a punching bag.

The next screen featured the singer on stage, his eyes looking far away as if performing to an invisible audience. I feel myself sneaking from screen to screen, attempting to peep at each character unnoticed.

Perhaps Choo intended this paradoxical experience for her viewers—for me to be an audience member and a voyeur at the same time. In the videos, characters that usually belonged on a big stage now performed in their own virtual spaces tucked away in corners.

On performativity and chance

By appearing on their own screen, the characters had their own stages and audiences, connected only by the time period they belonged in.

As shared in a text written by Dr Karin G. Oen on the works, the videos were “filmed as collaborative projects in which costumed performers [were] invited to inhabit their character, react to their environment and explore the character’s gestures and expressions.”

Given the autonomy to freely act in the video clips, the performers came alive as active agents in the work. Although recognisable from the costumes they wear and the spaces they inhabit, the characters’ movements and expressions seemed foreign, unlike the typical behaviour you would see while encountering these characters in those old, live amusement parks.

Take the video that struck me most, that of the jester. With her mask on, she inhabited what looked like an office, instead of being on the street. Never moving far away from a table in the centre of a room, her movements were slow, subtle and sometimes sultry, contrary to my memory of jester characters I have seen—often silly and comical.

Despite being less than an arm’s length from the screen, I felt far enough away from the performer, like an onlooker passing by, my presence fleeting, which encouraged me to linger and observe.

For the clip’s whole duration, I waited in anticipation for a climactic moment; for the scene to change or for the character to do something drastically different, strange, maybe even dramatic. Instead, the video played from start to end at a monotonous rhythm, with the characters in these worlds performing on a loop.

To dance without touching

Moving from screen to screen, my path within the exhibition changed as visitors entered and left the space. I could not help but feel like a performer within the work myself as if I was dancing to and from the front and the back of the stage to the dressing room.

Dancing Without Touching offered a new lens for me to consider our constantly changing and evolving realities. How Choo had literally layered imagery of olden-day amusement parks on top of scenes of present-day social distancing made me consider my position in each time period: the past, present and future.

It reminded me that sometimes I am an observer, looking at the world that passes me by in memorable events and eras. Other times, I am an active agent placed in settings that I can react to and influence others, just like the performers on screen.

____________________________________

The feature image depicts Choo’s Only nearer than half a world apart. Image credit: Yeo Workshop.

Sarah Choo Jing: Dancing Without Touching runs at Yeo Workshop until 26 February 2023. Click here for more information.