Last October, Natasha, the provocatively titled Singapore Biennale 2022, opened her doors to a public bewildered by the idea that an exhibition should have a name. Who is Natasha? And what does she, if we can even assume her gender, have to do with us?

Since then, Natasha’s fuzziness has drawn a fair share of criticism. Some reviewers were disappointed by the Biennale’s rejection of visual spectacle and inaccessibility, while others pointed to the gaps between her radical vision and its realisation in more concrete terms.

But if one thing is clear, it’s that through the act of naming, Natasha not only differentiates herself from the preceding editions of the Singapore Biennale, but also—with quiet audacity—declares her intent to redefine the biennale, a format that’s been around since 1895.

Given her insistence on flouting convention, it seems to me that we shouldn’t measure Natasha’s success against what we might expect a biennale to be (big, flashy, spectacular), but against the interventions that she proposes. To better understand Natasha’s aims, I spoke with co-artistic director June Yap to gain a more balanced picture of this sprawling enterprise.

Inner Spectacle

For all the criticism that’s been levelled against Natasha, she makes a necessary and laudable point: that we can’t go on churning out artworld extravaganzas, not after the pandemic, which has forced us to reckon with how fragile, damaging, and unequal our existing social systems can be.

“We did make a fairly clear mention in an early media conference that we are not looking to create a Biennale spectacle,” recounted Yap. In fact, one of the press releases maintains that Natasha will “[turn] away from the conventional preoccupation with the visual” and “dwell instead on interiority.”

Over the last two years, we’ve seen what I previously referred to as a wave of introspection sweeping over art exhibitions here in Singapore, and Natasha seems to be a culmination of this collective desire to pause and reflect. From meditative video installations to hushed soundscapes, the biennale is full of works that don’t reveal their secrets at first glance, instead demanding that we slow down and spend time with them.

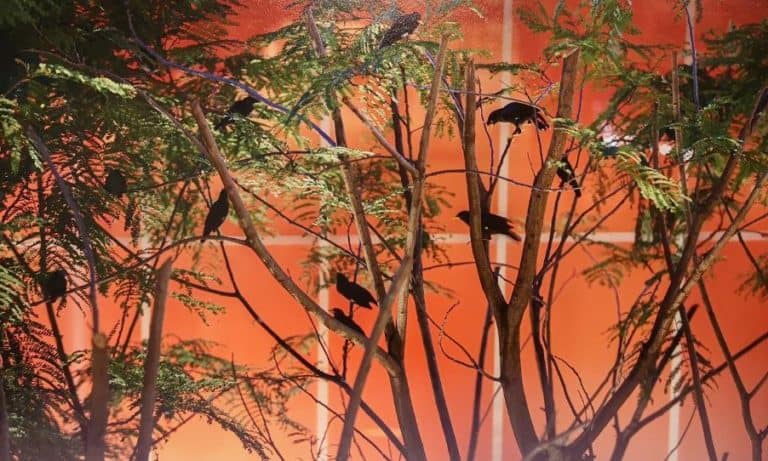

Lucy Davis, Alfain Sa’at, Zachary Chan, and Tini Aliman’s multimedia installation Talking in Trees (Like Shadows Through Leaves) Part 1 does this successfully. In a space enclosed by patchworked fabric, moving shafts of light filter through a bamboo pole structure, illuminating delicate botanical drawings and translucent embroideries. With birdsong and rustling leaves in the backdrop, Talking in Trees transported me into a half-imagined, half-remembered tropical jungle, seemingly altering the pace of time itself.

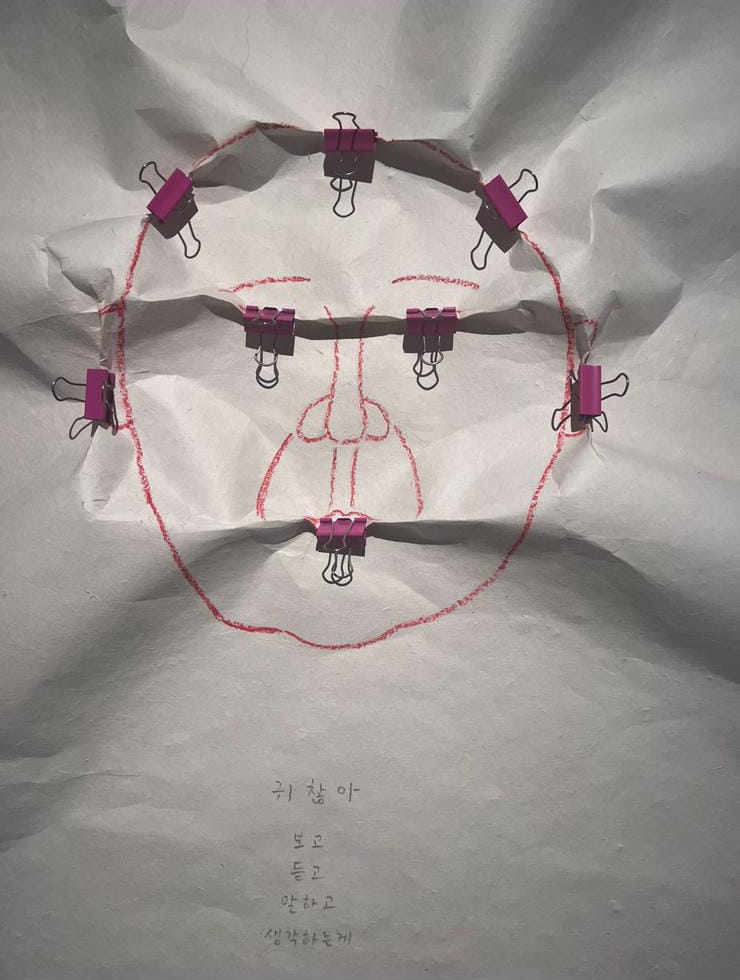

Shin Beomsun’s dissected kaleidoscope-turned-microscope similarly captures the biennale’s reflective tenor. This small optical sculpture invites you to peer through a pair of goggles at a minuscule image of yourself gazing into it—cleverly captured through an inconspicuous overhead camera. Sited close to the entrance of the Singapore Art Museum (SAM)’s Level 1 gallery at Tanjong Pagar Distripark, Shin’s sculpture provokes the inward self-scrutiny that Natasha demands.

“It’s more about thinking of the Biennale as an inner spectacle, as opposed to an outer spectacle, and seeing, claiming this space as important too,” said Yap.

While I think Natasha’s inwardness proffers a timely response to the pandemic, several works take this interiority too far, at the expense of accessibility.

For instance, the other components of Shin’s Tales in Stones (scholar’s rocks, sketches, and paintings) are presented as pictograms which encode their own narratives. Though scattered over a far larger space than the modestly-sized optical sculpture, I found these pieces much less effective. Their self-contained, esoteric system of meanings exists independently of our interpretation, foreclosing our engagement with them.

Donghwan Kam’s series of miniature house sculptures disappointed me. These contain fermenting soybeans which will be harvested at the end of the exhibition. They form part of the Nina bell F. House Museum, an ambitious multi-project platform aiming to dismantle colonialism, the patriarchy, and capitalism.

The gap between the project’s radical proclamations and its physical manifestations is glaring: we can barely see the lidded jars, and the sculptures display no measure of the process within. To connect domesticity, fermentation, and the critique of capitalism’s temporal regimes would require a feat of mental gymnastics.

While I believe that Natasha’s turn towards “inner spectacle” should be credited as a step in the right direction, finding the sweet spot between visual extravagance and contemplative interiority isn’t easy. Natasha occasionally falters on this front, with several works that seem to have been executed without due thought as to how viewers might respond to them meaningfully.

Considering the Biennale on a global scale raises further questions about the image that it presents of Singapore. Can Natasha’s overt rejection of spectacle be read as a refusal to fetishise the glitz and glamour of global capitalism? A Biennale flaunting Singapore’s wealth would be in poor taste, especially since much of the world and many here in Singapore are still recovering from the devastating effects of the pandemic.

But it seems naive to imagine that Natasha’s interiority would render her immune to gazes from the outside. The external world is still watching, and I’m not sure if Natasha necessarily showcases the “best of Singapore”. Plus, it’s no secret that many taxpayer dollars have been funnelled into the show, and it’s fair for Singaporeans to wonder what the Biennale does for us when it claims to turn inwards, while commissioning artists from all over the world and couching itself in the sleek, international language of contemporary art.

Time and Transformation

Another significant intervention that Natasha stages lies in her approach to artistic spaces. “It’s not just a production space—it’s a lived space […] that has its changes,” said Yap, acknowledging the fluidity of the artistic process. Works with a temporal dimension were consciously chosen for this edition of the Biennale, which aims to grow and evolve, like a person.

I was particularly impressed by Fragility Game, Daniel Lie’s site-specific installation at No. 22 Orchard Road. With a gargantuan floral wreath and sweeping stretches of jute fabric caked in decaying organic matter, the room’s potent, musky atmosphere reminded me that I was in the presence of other living, breathing, rotting things.

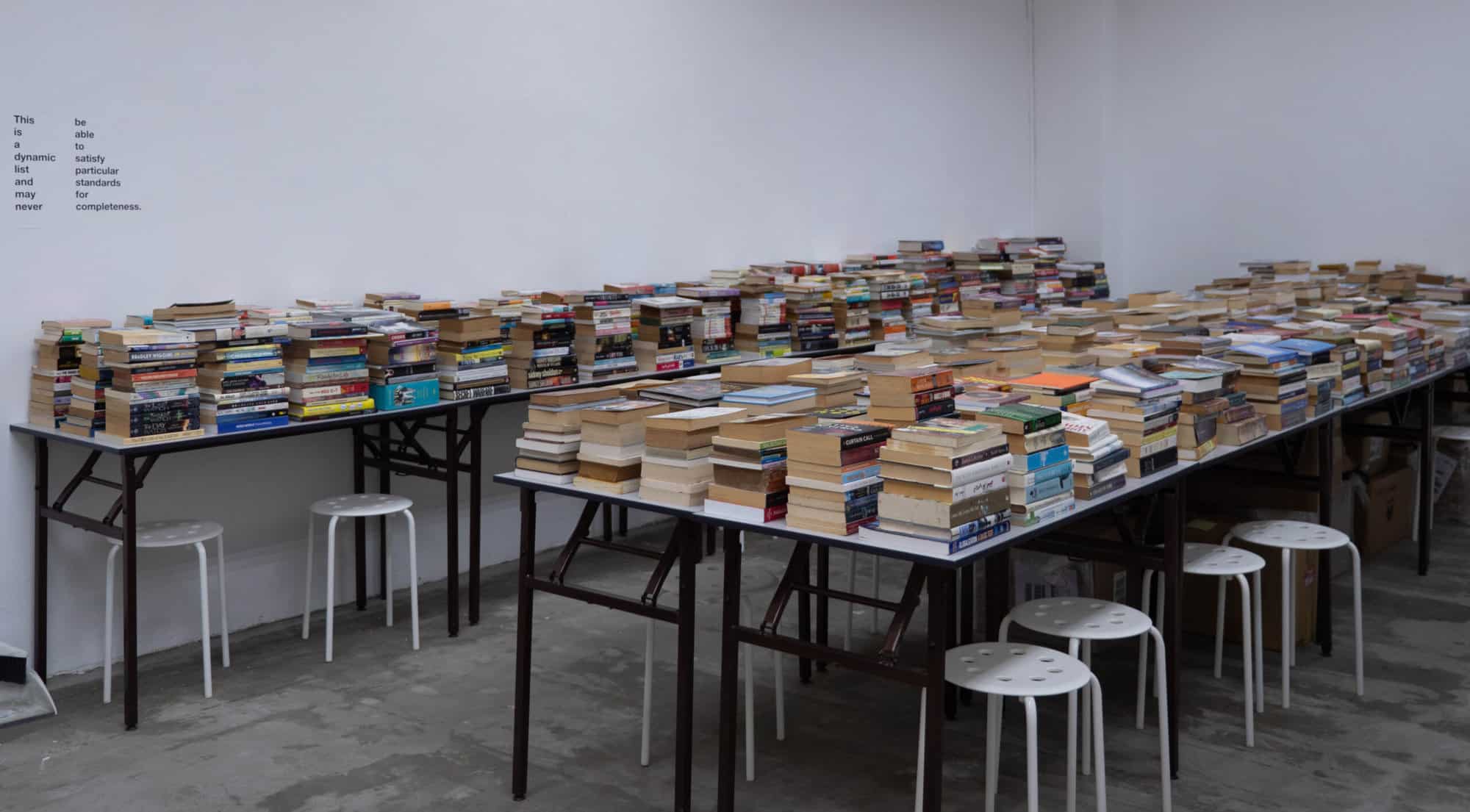

Over at International Plaza, Heman Chong and Renée Staal’s The Library of Unread Books brought to the fore the dimensions of time and change. Conceived as a communal, itinerant collection of donated books that were not read by their previous owners, the pop-up installation grows over the course of the exhibition and is constantly rearranged by visitors.

As a lived space for learning and artistic research, The Library of Unread Books resonated with Berny Tan’s three-month-long curatorial research project Page Break, which resulted in a multi-iteration installation at SAM. With gargantuan stacks of paper cut-offs assembled into seats for viewers, Page Break highlighted the materiality of the art book—a form that has been incredibly generative for artists.

I found Natasha’s sensitivity to the duration and temporal rhythms of art-making refreshing. The Biennale’s emphasis on ever-evolving artistic processes also comes through programmes and “activations” that present Natasha as a living, growing creature.

Yap explained that the programmes—for instance, art historian Jeannine Tang’s lectures on feminist human-cyborg entanglements in media art—were intended as artistic expressions in themselves. Several artworks, such as Zarina Muhammad’s Moving Earth, Crossing Water, Eating Soil, also featured performance activations over the duration of the Biennale.

These, however, could have been better publicised. The dates and times of the activations were not included in the exhibition directory, and I was disappointed to learn that Muhammad’s performance was over by the time I visited her work, which I very much enjoyed.

Audience Agency

Alongside Natasha’s focus on artistic processes is her interest in rethinking how audiences encounter art. “We want to acknowledge the time that they need to absorb the exhibition,” said Yap. Part of this was about encouraging audiences to carve their own narratives through the exhibition, rather than sticking to a rigid curatorial framework. “You’re not here to spend your weekend afternoon being in school. You have some agency in your experience,” Yap emphasised.

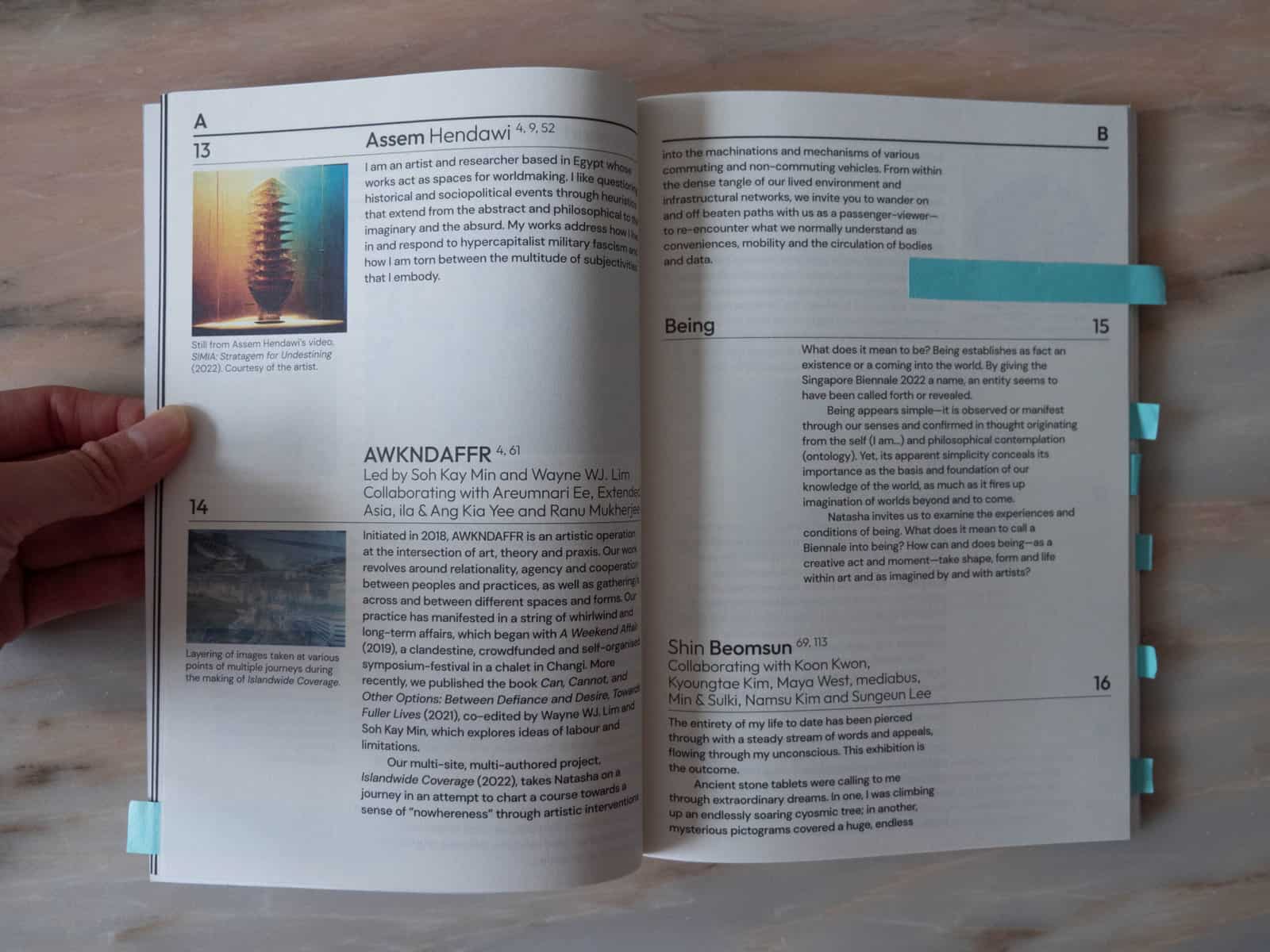

To this end, Natasha deliberately refuses to provide a clear curatorial pathway, be it in the form of section headers, or even a map with numbered artworks. The exhibition directory is also conceived as an “anti-guide”—instead of sequencing the artworks as they might be viewed, the directory consists of artist statements and thematic texts arranged in alphabetical order.

“We were quite mindful of even the captions that we were writing,” added Yap, stressing that the viewer’s personal experiences might shape her interpretations of the Biennale as much as the curatorial framing.

Certainly, it’s high time that audiences be given more credit for their ability to engage meaningfully with art, and I think Natasha’s approach to the question of agency is a welcome one, especially here in Singapore–where what we’re allowed to say, read, or watch is often monitored by government bodies who worry that we don’t have the discernment to respond sensibly to “sensitive topics”.

Poetic vagaries and non-commital politics

But the question of whether such a free-for-all curatorial approach works in the context of the Biennale remains quite separate. In my view, encouraging audience interpretation and providing a compelling discursive framework are not mutually exclusive options. In fact, I think Natasha would have benefitted from outlining her positions more clearly.

For one, Natasha is clearly gendered feminine, and several works—especially the multi-site Nina bell F. Museum—engage extensively with queer feminist politics and the aesthetics of care. There’s also the very visible fact that all four of the Biennale’s curators identify as female.

Yet, the question of gender is framed as one of rethinking binaries and multiplicities in the vein of broad humanism. “We want to pose these questions to everybody,” explained Yap. Could Natasha’s addresses have been made more specific, and therefore more potent? I think of the latest Venice Biennale, which unambiguously proclaimed its aim to rebalance the male-dominated artworld by spotlighting female and non-binary artists.

The naming of the Biennale also signals its focus on rethinking our relations to one another and to our environments. I was intrigued by the works with a clear ecological slant, such as Ong Kian Peng’s The Viscous Sea, a 6-channel video installation that traces the destruction of the Red Sea, and Angkrit Ajchariyasophon’s The Sanctuary, which documents a sustainable farming project in Chiang Rai, Thailand.

The themes that Natasha gestures towards—kinship and care, community, ecological sustainability, spirituality and animism—are certainly pertinent post-pandemic. But again, I wonder if these political-aesthetic commitments could have been made more explicit.

Rather than withdrawing the curatorial hand to make space for audience agency, perhaps foregrounding the curator’s voice in all of this—by highlighting the guiding principles behind the selection of works, for instance—could have sparked thematically-resonant debates.

Several steps forward

On the whole, Natasha’s bold visions are undermined by the noncommittal, poetic vagaries of the many narrative threads that she tries to hold together. In her desire to remain open-ended and to dismantle binaries, Natasha blurs the perimeters of our engagement with her, to a point where we’re not sure what to look at.

Uncertainty can, of course, prompt curiosity and questioning. But without visual and conceptual anchors (remember, the Biennale turns away from spectacle) to keep us tethered to the thematics she hints at, I found it difficult to orient myself in the transformative journey that Natasha promises.

Despite these shortcomings, I do think that Natasha makes several important strides forward: firstly, in raising the question of what Biennales should look like in this new climate; secondly, in opening up spaces for considering art as a process or situation rather than just an object; and thirdly, in crediting audiences with greater agency.

Natasha is keenly aware of the fact that the biennale format—which has its roots in the colonialist international trade fairs of the late-19th century—runs the risk of becoming obsolete today. And to her merit, she’s not afraid of experimenting with it to bring it up to date.

So, if you haven’t, pay Natasha a visit, and get to know her on her terms. You might be disappointed, and you’ll probably be left doubting. But, perhaps, the point isn’t to find answers, but to ask questions.

The 2022 Singapore Biennale Natasha runs till 19 March 2023. Click here to find out more.