How intimately can we know an artist from the subjects she captures?

Emiria Sunassa was many things: a nurse, a singer, a self-proclaimed “Queen of Papua” and a painter whose arresting portrayals of life across the archipelago has earned her acclaim as a pioneer of modern Indonesian art.

Now a selection of these works shines a light on the artist’s own multifaceted identity as part of an exhibition at National Gallery Singapore’s Familiar Others. In this vast former Supreme Court building, the exhibition occupies a cosy three-room project space, Dalam Southeast Asia, dedicated to lesser-known narratives in Southeast Asian art.

Intimacy and alienation

Sunassas’s portraits of indigenous Papuans are intimate but alienating. Her naked Irian man fills the foreground, his white eyeballs fix us with an arresting stare. But he is dark-skinned and shadowy, only the occasional thick electric green brushstroke separates him from his murky background.

“The dark, rough skin… although criticised by conventional art critics, is actually the antithesis of how mainstream art tries to glorify images of beautiful and exotic bodies,” contemporary Indonesian artist Citra Sasmita, who, like Sunassa, draws on the natural motifs and traditional iconography of her Balinese heritage, tells me in our conversation about Sunassa.

But here it seems to diminish the nameless man, blending him into his surroundings.

The colourful birds of paradise he clutches to his chest were a popular trophy of the burgeoning trade between Europe and Southeast Asia at the time, a potential offering from a slave to their colonial master, to the audience, or perhaps to the artist herself.

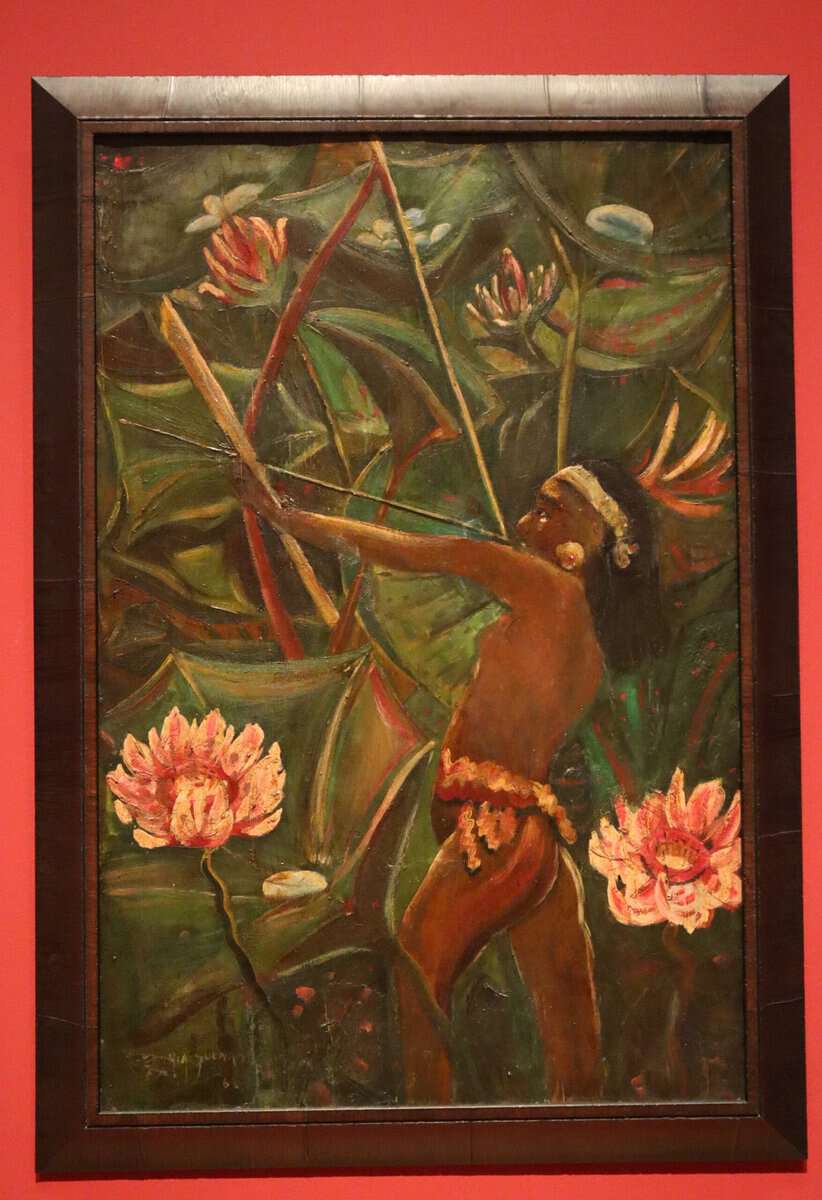

This uneasy balance between countryman and coloniser, closeness and distance, weaves throughout the exhibition. In Danger lurking behind the Lotus, we are drawn into the world of the Papuan archer, whose body and bow stretch the dimensions of the canvas as he turns towards an unknown threat. He is dynamic but generic, combining various features from across the over 300 indigenous tribes that call West Papua home. He stretches his weapon against an ethereal patchwork of verdant leaves and oversized lotus flowers.

These people were familiar to Sunassa. She lived and worked with them, she knew them so well she could paint from memory. But here they are exoticised pan-Papuan aliens, residents of exoticised, indeterminate surroundings. Sunassa’s education, class and international travels created a distance between herself and these people she considered both her artistic and regal subjects. The generalised features and the abstract backgrounds reflect the popular perception of Papua at the time as a “dark, unknowable space,” amongst the cosmopolitan Batavian or Jakartan societies where her work was presented.

A royal claim

Imagination and myth surround Sunassa’s own background. Born in 1984 in a settlement on Tidore Island, part of the east Indonesian Maluku archipelago, her studies in the colonial European school system ended at third grade. In adulthood she carved multiple careers and lives across the Dutch East Indies and Europe. She trained as a nurse but by the 1920’s she was said to be working as a singer and pianist at a Dutch society club in Ternate.

Later, she worked in plantations, mines and factories and lived amongst ethnic groups across Papua, Kalimantan and Sumatra, where she was known variously as “Elephant hunter,” “Poison maker,” and “Tiger woman.” While her (male) contemporaries at PERSAGI (Association of Indonesian Drawing Masters) focused on revolutionary Indonesians, mainly around Java, she turned her focus to marginalised ethnic communities.

Throughout multiple shifting identities, one thing she remained consistently sure of was her royal lineage. Sunassa claimed to be descended from the Sultanate of Tidore and later attempted to extend this regal reach.

In 1949, the Dutch handed sovereignty of almost all of Netherlands New Guinea to Indonesia. In this first flush of post-colonial nation-building, Papua was a disputed territory: claimed both by Indonesia and the Dutch, who retained sovereignty to prepare the area for independence. Around that time Sunassa painted both Danger lurking behind the Lotus, and Irian Man with Bird of Paradise, and put in a claim to be the rightful ruler of Papua at a Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference in The Hague.

Her claim was never officially supported.

Connections with communities

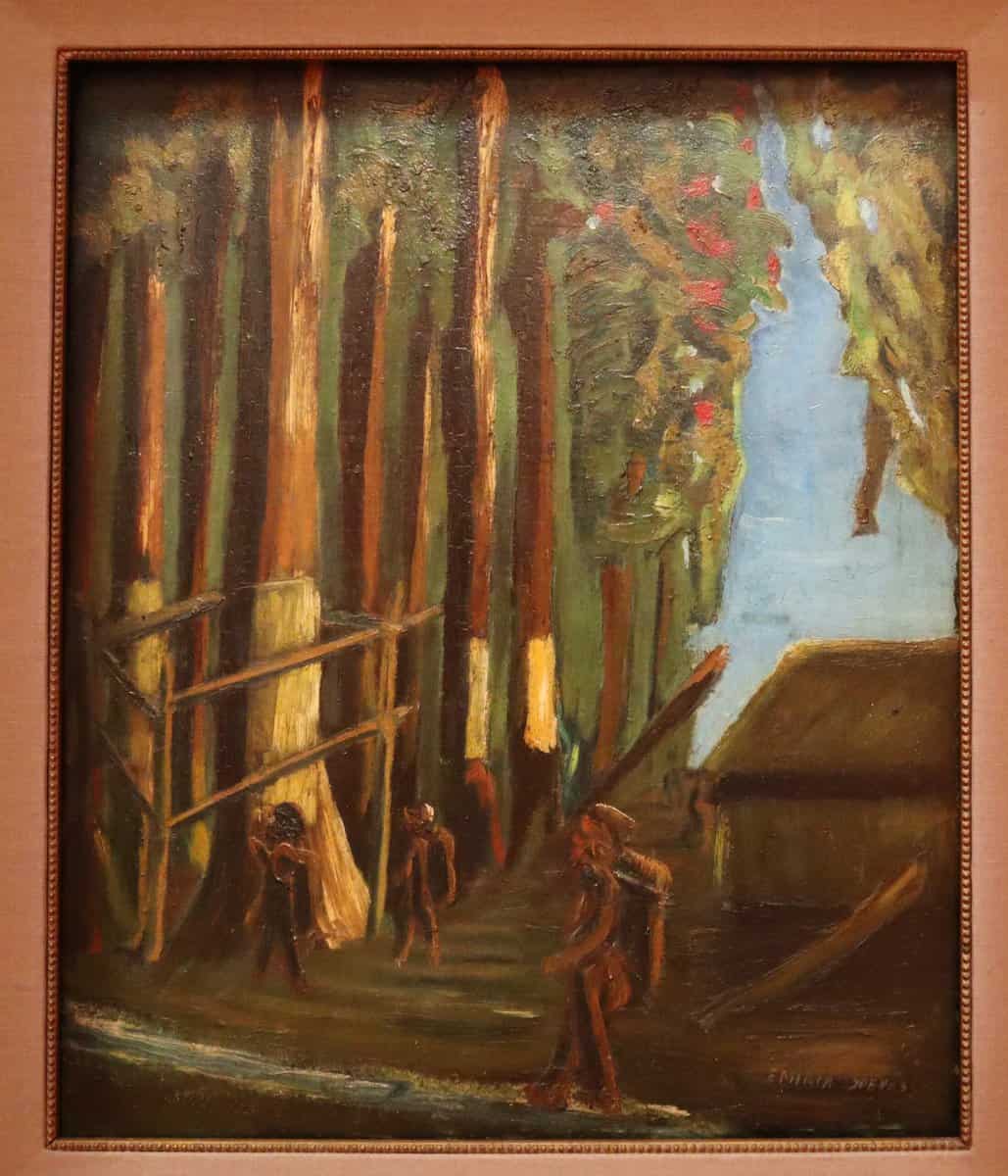

In Rosin Harvest, Sunassa creates a link with her subjects through the theme of shared roots. Three figures dwarfed by trees stretching the height of the canvas like Roman pillars, come to extract damar resin, a popular natural commodity traded from Sunassa’s birthplace Timor. Her thick heavy brushstrokes were sometimes deemed “primitive,” by art critics, a word also applied by her contemporaries to the communities she depicted.

But at the back of the painting is a regal reminder, a separator of status. Sunassa signed her initials Emiria S. W.P.A A.M.T, a noble title and marker of her Tidore royalty.

Sunassa herself is an alien in this exhibition, the only self-taught artist and the only woman. Painting against the grain of a culture where, according to Sasmita, “women who paint are only seen as mere hobbies…counter-productive… unable to contribute ideas,” Sunassa occupied her own ‘otherness,’ rejecting both the trope of woman as muse and the masculine revolutionary subject matter of her male contemporaries.

In the detailed feathers of a bird of paradise or the thick blush streaks of lotus petals, she reflects the animalist spirituality practised by indigenous communities before colonial conversions to Christianity, and celebrates Papua’s natural landscapes at a time when both women and nature were objects to be colonised and control.

Her companions in Familiar Others are two of her 20th-century Southeast Asian contemporaries, Eduardo Masferré (1909 – 1995), the Filipino-Catalan photographer whose photographs captured the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera region and Yeh Chi Wei (1913 – 1981), a first-generation Singaporean artist whose paintings of Borneo locals weave in memories of his own childhood in Sarawak.

All three had familial connections with the communities they captured. All three tread the thin line between familiarity and distance, both embracing and alienating their subjects.

Is there a spectrum of Othering?

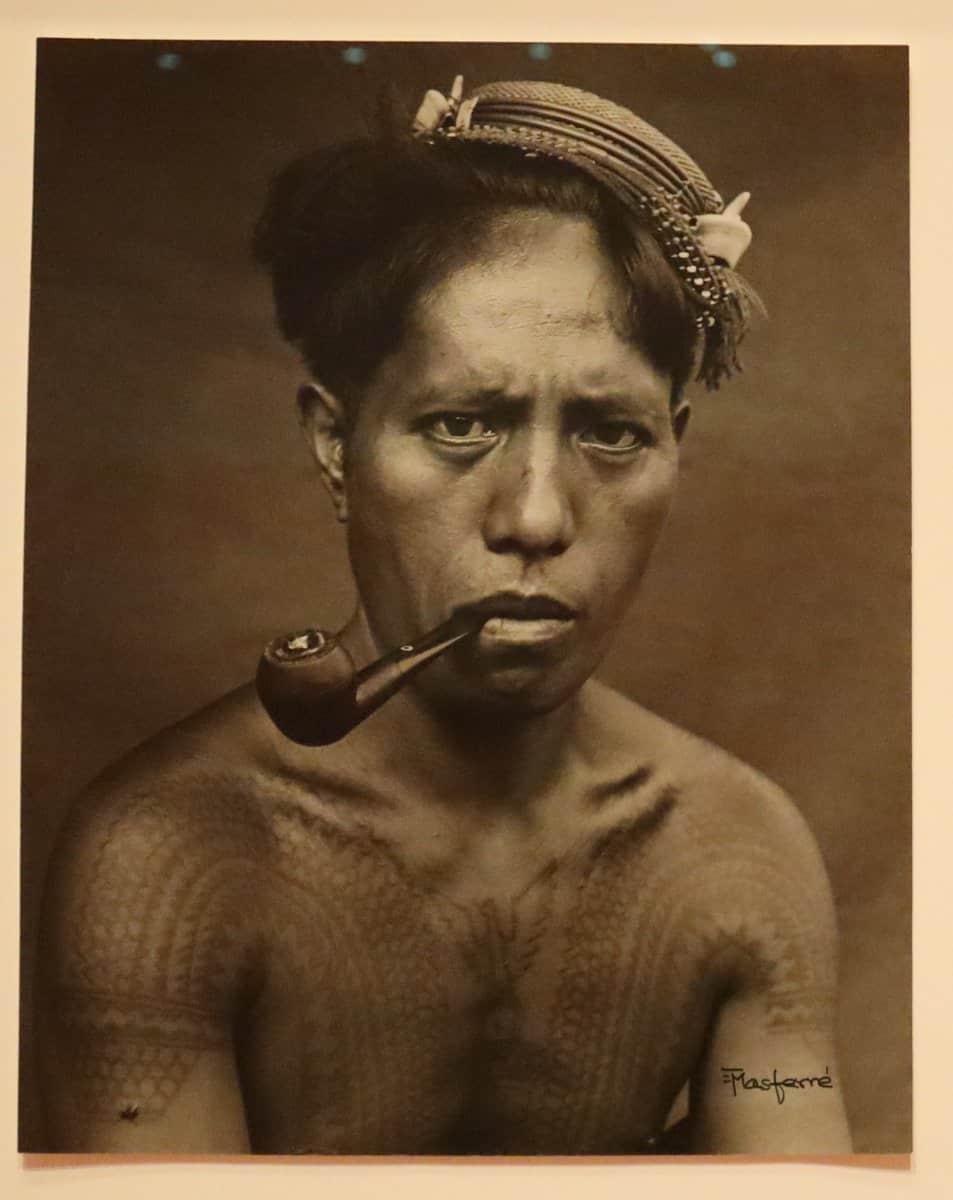

Sunassa’s Papuans, with their vivid stares and defined features, appear more human than Yen Chi Wei’s elongated faceless Dayak musician. Her oil paintings are arguably more empathetic than Masferrés monochrome photo of a Young Man from Makedkong, which confronts us as we enter the exhibition with his arresting stare, pipe dangling from his lips, soklong basketwork hat lopsided on his head, the wings of an inked American eagle flanked by other traditional tattoos mapped across his bare chest.

A selection of assorted pottery sits next to a pack of anthropological photos in a display cabinet. In his travels, Yen amassed pieces of ceramics, combining Southeast Asian artefacts with Chinese pieces reflecting his own diasporic roots. It’s a neat visual metaphor for the exhibition as a whole: a collection where fragments of appropriated foreign cultures and our own perceived heritage mingle.

Issues of Identity

In an age of social media scrutiny and intense navel-gazing, the questions ‘Who am I?’ and ‘Who are you?’ are conundrums of centuries of philosophy and hundreds of TikTok videos. For West Papua (which remains under the control of the Indonesian government), where the bloody tussle for independence continues, hitting headlines most recently with the West Papua Liberation Army’s abduction of New Zealand pilot Philip Merthens, themes of identity and belonging are embroiled in more problematic political debates.

For Sunassa, Familiar Others highlights how these two questions are interlinked and interdependent, especially when it comes to diaspora or migrant communities. Sunassa’s work explored indigenous Papuan identity. ‘Familiar Others,’ shines a spotlight on her own.

____________________________________

Familiar Others runs at the National Gallery Singapore till 14 May 2023. It is located within the project space Dalam Southeast Asia, dedicated to lesser-known narratives in Southeast Asian Art. Click here to find out more.

Feature image credit: National Gallery Singapore