It’s unlikely I’ll eat at Odette again, though not because I didn’t enjoy the beautiful lunch that Chef Julien Royer has put together in celebration of the National Gallery Singapore’s latest exhibition City of Others: Asian Artists in Paris, 1920s–1940s. I’m just not a fine dining sort of guy — usually favouring the unrestrained (some might say rough) flavours of old-school zi char or hawker fare instead. I am more of a gourmand than a gourmet, preferring hearty food and drink to refined plates.

There were things I did love about the lunch (a four-course affair meant to complement the Gallery’s blockbuster show on migrant artists in Paris), and I’ll speak of them later. But as the meal progressed, an emerging disjoint troubled me.

Despite the billing as a celebratory lunch for the exhibition, the links between the food and the art seemed an afterthought (and sometimes fainter than that). The slightest hint of cross-cultural interactions was suggested in the use of Asian ingredients (chutoro, dashi, ponzu, shiso, ikura, and, most memorably, kampot pepper for the crusted pigeon) in modern French dishes, but this theme was left undeveloped.

The predominance of Japanese ingredients also seemed frankly unimaginative — after all, these ingredients are now pretty much de rigueur in dining. A glance at the exhibition reveals that Paris drew in Asians of many other ethnicities. I found myself musing on the missed possibilities of gesturing to these other cultures and cuisines: Indian, Vietnamese, Chinese, Korean, Indonesian, and Malayan, all represented in City of Others. (A slightly dry and under-seasoned pigeon bao was the only attempt at this, but it underwhelmed.) The closest I came to any art discourse was when the charming restaurant manager dripped some drops of verbena oil on my dish of Normandy brown crab. “I’m not an artist, but I will try,” he quipped. (“That’s actually quite pointillist,” I responded.)

I do think it’s possible to pair food and art well. I had the chance some months back to try out cocktail bar ANTI:DOTE’s high tea set, designed in honour of Singaporean artist Lim Tze Peng. Though I was initially afraid that this might prove tacky, especially after Lim’s passing in February, the set adroitly adapted visual motifs from his work, such as attap houses and boats from his iconic Chinatown and Singapore River scenes, into teatime treats.

Singaporean flavours like bandung, kopi, and chicken rice were also, overall, thoughtfully incorporated. At the very centre of the set was a recreation of a famed calligraphy piece, 家和万事兴 (Harmony in the Home Leads to Prosperity), in the form of a sandwich biscuit filled with dark chocolate cream and set on a miniature easel. Created in collaboration with the gallery Ode to Art (which worked closely with the National Gallery Singapore to present Lim’s final retrospective Becoming Lim Tze Peng), the tea set proved to be a surprisingly fitting tribute to the great artist.

But a high tea set designed as a tribute to an artist is quite different from a finely calibrated four-course meal by a Michelin-starred chef. While I got nary a whiff of the exhibition during lunch, I felt the full force of Royer’s vision. An emphasis on terroir was ever-present, exemplified by the use of ingredients from his native Auvergne.

A light, airy donut, filled with a creamy, earthy Saint-Nectaire cheese from Auvergne, was a brilliant beginning to the meal. The scallop dish incorporated dried meadowsweet, a herb plucked by Royer’s mother. (Odette is, of course, named after his grandmother.) While I found the flavours overall too subtle for my liking, the meal had the undeniable, verdant energy of spring.

Perhaps, then, it was too much to expect a chef-auteur to subordinate his vision to those of other artists. Let Royer create his own art in Odette, then go upstairs to see how Asian artists of the fervid interwar years (Années folles or the “crazy years,” roughly equivalent to the “Roaring Twenties”) absorbed and refracted the City of Lights.

Pairing Odette’s dishes and City of Others

Nonetheless, since you will get a complimentary ticket to City of Others if you book this lunch, I’ve taken the liberty of pairing some of the dishes with pieces you’ll see in the show:

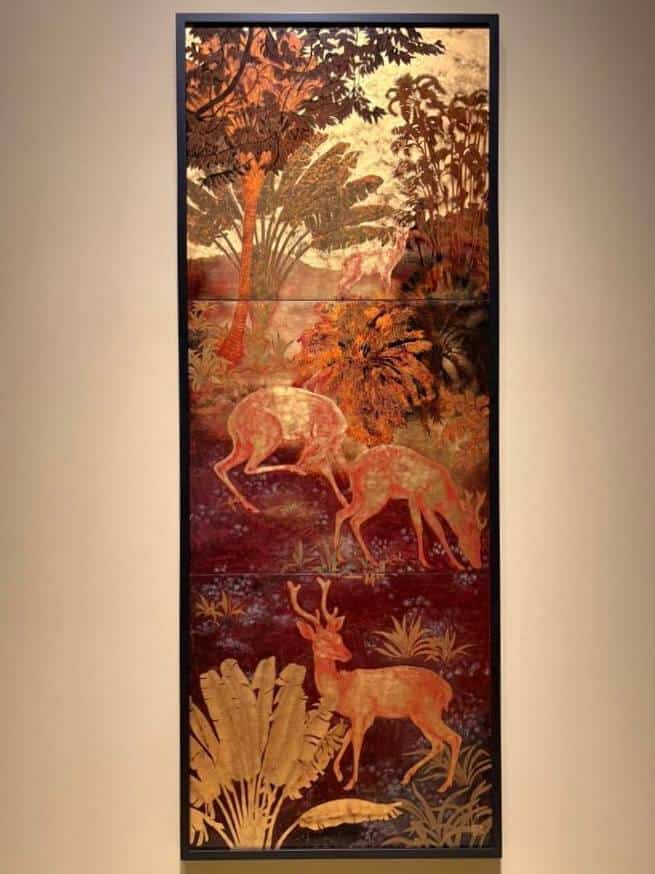

1. Phạm Hậu’s Family in a Forest (c. 1940) alongside Odette’s signature amuse-bouche of mushroom tea and sabayon with puffed buckwheat and walnut, accompanied by a mushroom brioche. The autumnal colours of this stunning work in lacquer, a Vietnamese craft tradition that influenced the French Art Deco movement, accompany the earthy yet frothy amuse-bouche perfectly.

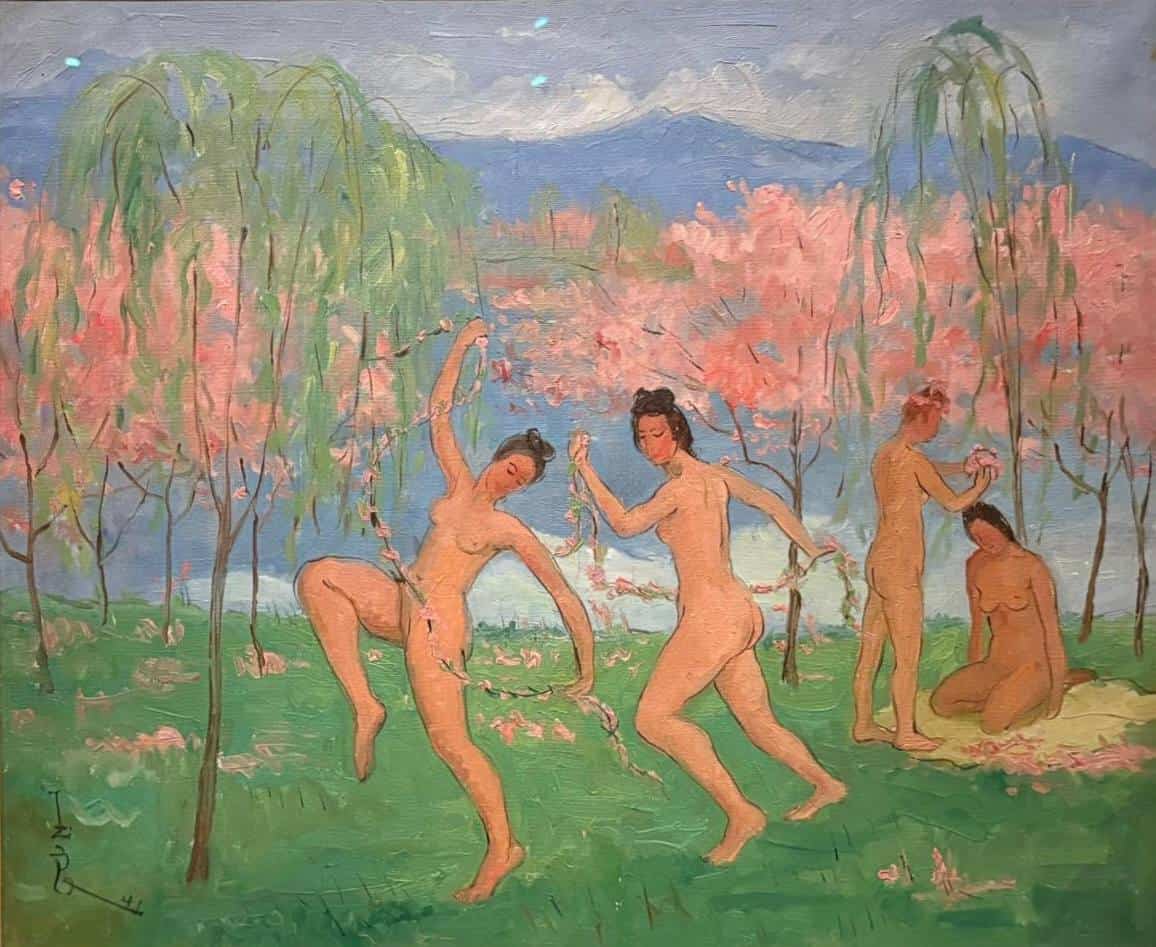

2. Spring announces itself in the form of naked maidens dancing among willows in Song of Spring (1941) by Pan Yuliang, known as China’s first woman painter in the Western style. You might feel the same uplifting lightness in the butter that comes with the bread course, which is blended with garlic, parsley, crème fraiche, and fromage blanc.

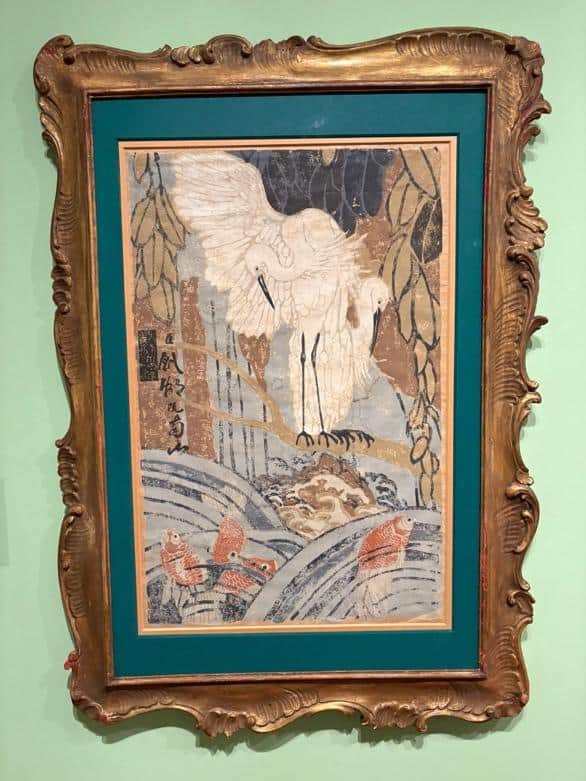

3. Imagine yourself as a triumphant crane, about to seize your catch, in Nam Sơn’s woodblock print Aigrettes et poissons rouges (Cranes and Red Fish) (1927). In their case, these brilliant red fish. In yours, Normandy crab, accompanied by sugar snap peas, a horseradish ice cream, and a velouté of crab dotted with verbena oil.

4. As you tour the exhibition, the shell shape in abstractionist artist Okamoto Tarō’s Counterpoint (1935, remade 1954) might bring back fond memories of Royer’s seaweed butter-poached scallop served with green asparagus, meadowsweet, and wild garlic. In the 1930s, Okamoto became the youngest member of Abstraction-Création, a group of Paris-based artists who explored abstract art.

5. Lastly, have your coffee and douceurs with Liu Kang’s painting Breakfast (1932). The influence of French artists, especially Henri Matisse, is particularly strong here. Paris proved incredibly formative for Liu Kang, who studied and lived there from 1928 to 1933, thus gaining the chance to study paintings that he had previously only encountered in reproductions. “Matisse influenced me in many ways — the pursuit of innovation, the expansion of bold vision and the sublimation of images,” he once said.

___________________________________

The Odette x City of Others lunch experience is available from Tuesdays to Thursdays until 14 August 2025 at $298++ per person, including complimentary access to the City of Others exhibition. Reservations can be made at sevenrooms.com.

City of Others: Asian Artists in Paris, 1920s–1940s is on view at the National Gallery Singapore till 17 August 2025. Visit nationalgallery.sg to purchase tickets and find out more.

This was an independent visit, paid for by Plural Art Mag.

Header image courtesy of Odette.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

Sight, Sound, Style: 5 Stores to Check Out at Millenia Walk, an Arts-Meets-Lifestyle Destination in the City

‘Tis the Season! International and Local Artists Take Over Millenia Walk — A New Way to Look at the Ordinary

Red House Cafe : Celebrating the History of a Bras Basah Bakery