- This event has passed.

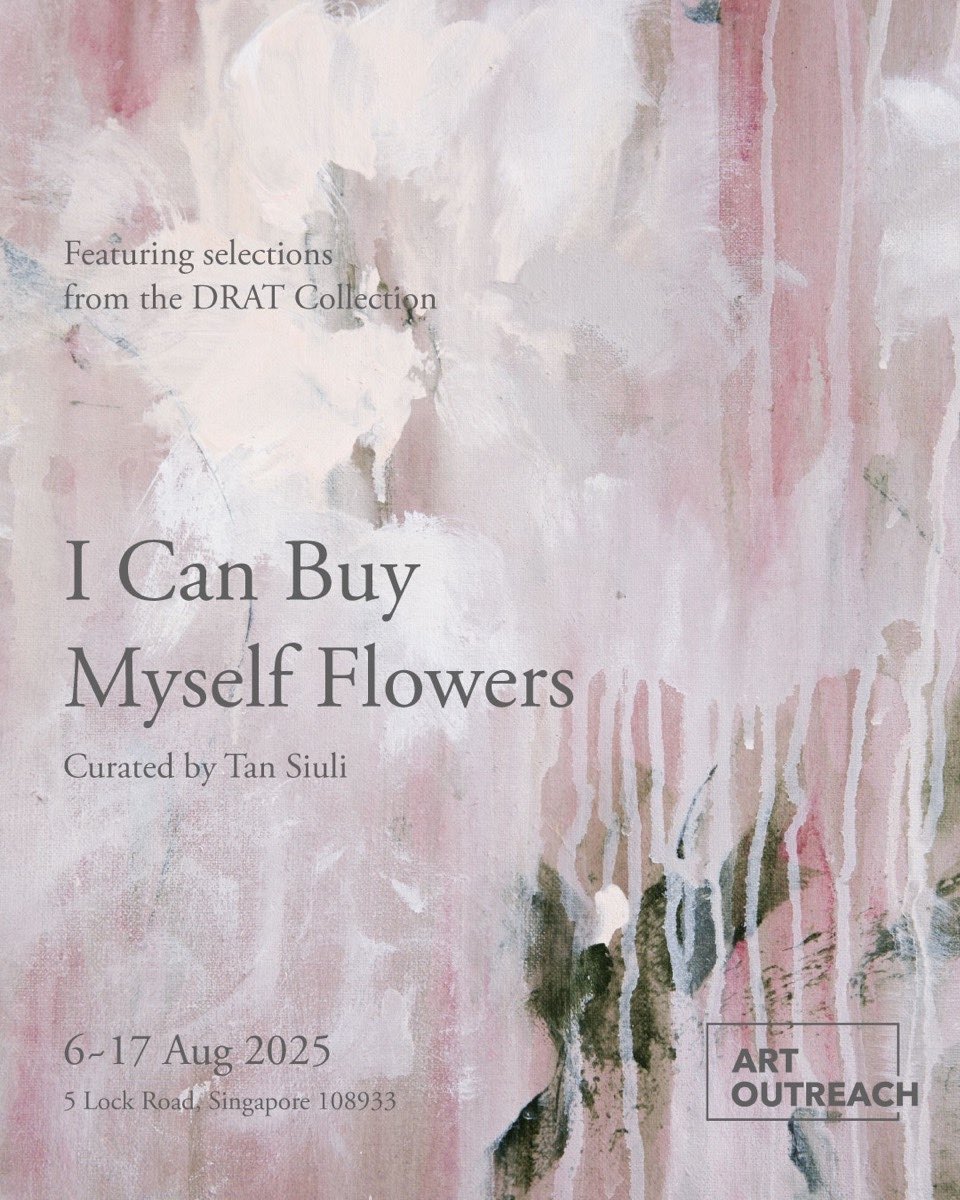

I Can Buy Myself Flowers

I Can Buy Myself Flowers

Group exhibition | Featuring selections from the DRAT Collection

Opening Hours:

11am—7pm | 6 to 17 Aug 2025

Location:

Art Outreach Singapore

About:

Titled after the lyrics of a pop song celebrating independence and self-sufficiency, I Can Buy Myself Flowers brings together works drawn from a private collection and focused on the subject of flowers. Floral imagery has a long and illustrious art history, and artists throughout time have been captivated by their universal language of beauty, emotion and meaning. To bring together an exhibition focused on this singular theme is hence an opportunity to consider the myriad approaches to the same subject, and how the simple motif of the flower can encapsulate the complexities of human experience and artistic expression across time, cultures and contexts.

With works spanning the impressionist period, modern masters, and some of the most exciting names shaping art today, I Can Buy Myself Flowers offers a glimpse into a multiplicity of biographies and ways of viewing the self and the world, even as individual works echo or pay homage to others, and to art history.

Maurice de Vlaminck’s still life continues the long history of this genre but his loose brushwork imbues his subject with a sense of flux, flying in the face of classical painting conventions of permanence and fixity, and a nod to the Impressionist obsession with capturing shifting light – and by extension, the transience of life, vision and matter. Sanam Khatibi’s botanical arrangement echoes this darker palette and sentiment, recalling both the vani t as paintings of the Dutch golden age as well as the sensuous meticulousness of Persian miniature painting. In her still life, we catch a glimpse of the savagery of the natural world, under the polished veneer of beauty, order and control. Clare Woods’s lush bouquets turn on a similar latent tension, her energetic, visceral brushstrokes contrasting with the inevitable decay of her subject matter. In her words, “the idea of a vase of flowers represents a life span, in a tiny environment”. Woods’s vivid, expressive paintings may be read as a rage against the dying of the light, and a reaffirmation of life, joy, and pleasure.

While flowers are celebrated and enjoyed for their beauty and fulsome lushness, they can also be poignant intimations of loss. Iranian-American artist Rosha Yaghmai’s vivid blooms float adrift against a glassy pool of black, a nod towards the legacy of Monet’s ethereal waterlilies as well as a haunting metaphor for un-rooting – the spectral traces of a ‘phantom land’ that the artist has left behind. In a similar vein, the delight in Bianca Raffaella’s lush and textured florals is tempered by the knowledge that the artist is partially sighted; her resplendent visions share a kinship with the near-abstract paintings that Monet produced when his eyes were clouded by cataracts, and their fleeting beauty is also the ache of a brief and momentary joy that we all too often take for granted.

Two immigrant artists draw on the image and idea of the garden as a means to express delight and anxiety respectively. With a nod to the joie devivre of Matisse’s paintings as well as the vivid acrylics of Pop Art, Walasse Ting’s “My Garden” is a sensuous field of colour, a profusion of unbridled joy that admits no hints of the turbulent times he lived through. Ting’s work is a foil for Paul Anthony Smith’s equally vibrant garden, but Smith’s is one that is out of reach and encircled with a chain-link fence – a sombre reference to the lived experiences of black émigrés in America.

Another émigré artist, Liu Dan chose to eschew the hardships of the Cultural Revolution in his homeland, electing instead to celebrate in his art the great traditions of east and west, bringing these together in his inimitable synthesis of drawing, ink painting and calligraphy. In its references to Van Gogh — both in choice of subject matter as well as a quotation from one of Van Gogh’s letters — Liu’s work expresses a keen desire to be regarded amongst (artistic) peers. In a similar fashion, Evelyn Taocheng Wang’s painting turns on citations, cannily marrying the minimalism of Agnes Martin’s visual fields with evocations of the void or negative space in traditional Chinese landscape painting. With a deft hand and a light touch, Wang playfully punctuates registers of the transcendental and profound with seemingly misplaced quotidian observations, revealing her fluency in the visual language of the Chinese literati as well as that of the contemporary avant-garde.