“I would probably keep painting, keep working. I struggle to know where to stop.”

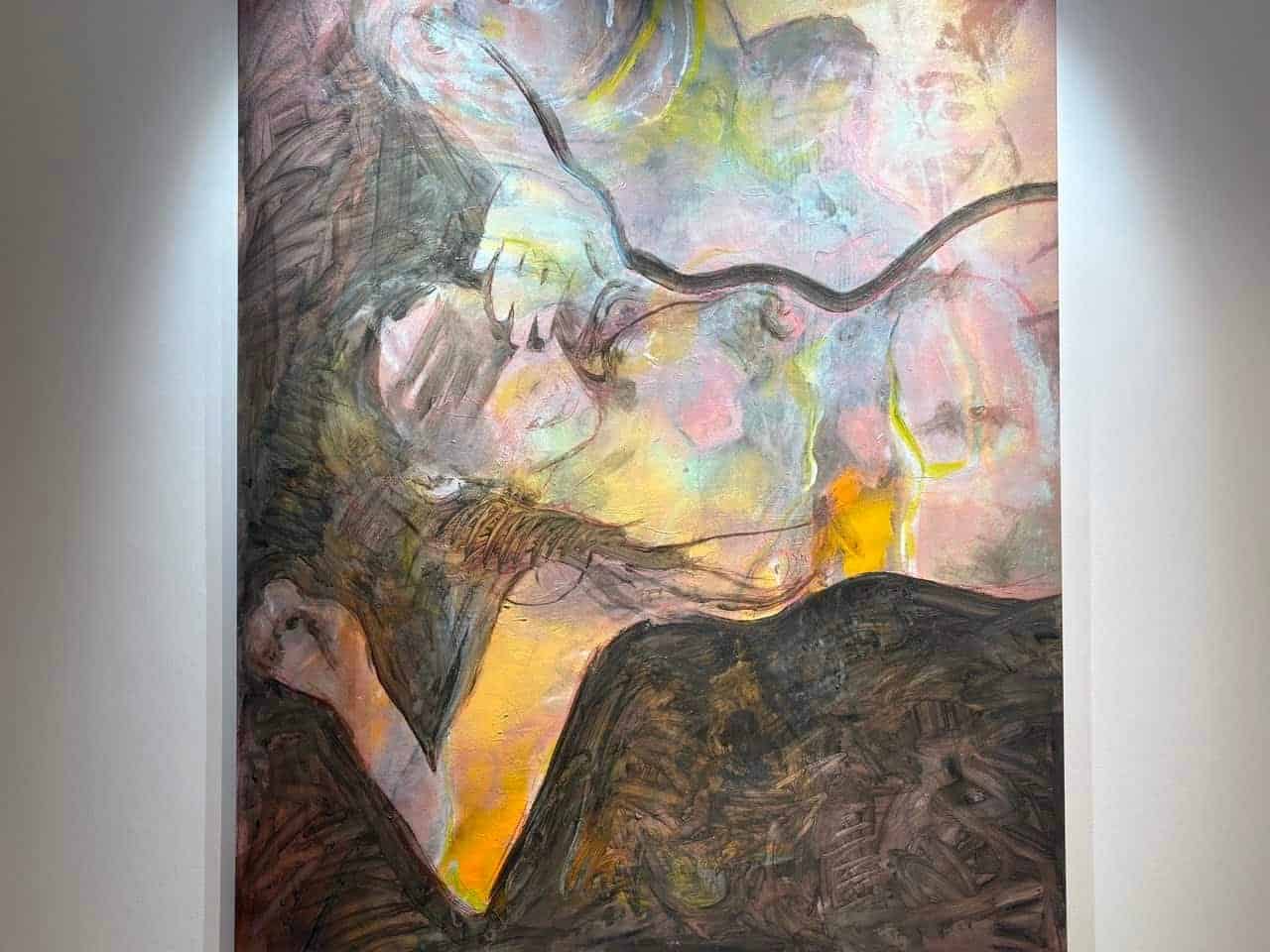

I’m standing in front of a painting with the Italian artist Giovanni Leonardo Bassan. Giada and George (2025) is a large-scale portrait of a laughing woman, whose skin glows with luminous pinks, oranges, and greens, like the inside of a shell lined with mother-of-pearl.

Bassan has just explained to me that he sometimes relies on an exhibition deadline to decide when a piece is done; if a work somehow came back to him, he might just pick up where he left off. He speaks as though canvases — built up quickly and intuitively, translucent layer by translucent layer — have lives of their own: “When it ends, it’s almost like killing the piece.”

Running at LOY Contemporary Art Gallery till 30 May, Non c’è Rosa Senza Spine (Ain’t No Roses Without Thorns) is Bassan’s first solo exhibition in Singapore. Centred on portraits on friends from his artistic community in Paris, where he’s now based, the exhibition illuminates multiple aspects of Bassan’s practice: careful use of material and colour, idiosyncratic stylisation of the human form, and attentiveness to the unseen web of relationships that tangles us together.

Material matters

On the left side of the gallery, there stand three ceramic pieces on white plinths, as well as a severe, triangle-shaped chair. Though these are the only three-dimensional works in the show, they represent an important strand of Bassan’s oeuvre.

The chair is a piece by well-known fashion designer Rick Owens, whom Bassan has worked with for over fifteen years. Descended from five generations of furniture makers, Bassan has served as the Rick Owens house’s Head of Furniture since 2018. Next to this tribute to his longtime mentor, Bassan has placed some of his works in ceramic, a medium he has been experimenting with for roughly four and a half years.

The works consist of modular ceramic tubes, threaded onto upright metal rods. The central work is topped with a crudely shaped head with deep hollows for eyes, while the two flanking works take the form of contorted arms and hands reaching for the sky.

Bassan explains that he does a lot of testing to ensure his ceramic pieces turn out the way he wants them: trying out different clays and glazes, experimenting with different firing techniques, and even going so far as to make his own glaze. His acute attunement to material shows up in his paintings as well, which are often executed not on canvas but on wool army blankets — a callback to his furniture work, where he often uses the blankets to cover floors.

Worked over with oil, acrylic, or pastels, the rough surfaces of the blankets call to mind bark crusted with moss and lichen, or dirt on a forest floor, endowing the works with novel textures and a quite literal warmth.

Bodies in colour

While Bassan’s practice centres on the human form, he is far less interested in realistic representation than in entering a realm of unrestrained feeling and sensation. Bodies are less subjects in themselves than conduits to express more abstract emotions and experiences. Take, for instance, Thomas, whose three-dimensionally rendered torso and arm abruptly morph into a rubbery, cartoonish hand, or Giada, whose head and chest are delineated with little more than a few dark smudges and skeletal white lines.

Often, it is through colour that Bassan achieves his intense emotional effects. In the first area of the gallery, facing the street, two large portraits in lurid reds, yellows, and greens stand in contrast to the softer pastel tones that tint much of the show. On the left, Benjamin seems lost in thought, his ambiguous expression bathed in traffic-light hues. On the right, Matheus stares out at the viewer, his face cast in dramatic shadows. Pale, translucent shapes overlay and accent each portrait: for Matheus, a ghostly presence on his shoulder, and for Benjamin, something resembling a set of bones or leaping figure.

Further into the gallery, Salym employs a different set of colours — sunset oranges, oxidised-copper greens, and pearlescent pinks — but presents a similar sense of mystery. Murky architectural details, a giant hand, a bespectacled man, and a figure tipping up a bottle for a drink suggest some complex or even sinister narrative.

But though Benjamin, Matheus, and Salym all bristle with unspoken stories and barely contained feelings, the specificities of those stories and feelings remain utterly unknown. Bassan’s canvases are at once full of layered colour and detail, yet strangely blank — opaque enough for viewers to see their own personal histories, assumptions, and biases reflected back to themselves.

All together now

In Non c’è Rosa Senza Spine, the knowledge that the faces in the portraits are not anonymous sitters but Bassan’s friends produces an uncanny feeling. To the artist, each of these faces represents a wealth of feelings and stories — he’s previously described his paintings to Vogue Italia as “an accumulation of memories” — but to us, the viewers, they are perfect strangers, made more distant still by Bassan’s abstract style. We are allowed to step into his circles, his life — but only so far.

A set of related works, Study of a Portrait (2023) and Self Portraits (2024), further complicates the relationships in the exhibition. The former, painted on transparent gel, features a close-up of a face in three-quarter view, a hand resting beneath his chin. In the latter, Bassan zooms out from this image, revealing a sleeping figure tucked quietly beneath the hand’s caress.

Why split your own self portrait in two? Mysterious as Self Portraits is, it also seems to provide a key to the exhibition. It suggests, perhaps, that we are not singular, discrete, isolated beings, easily graspable and proudly sectioned off from the rest of the world, but rather defined by relationships, to each other and ourselves.

Bassan pushes this furthest in Andres (2025). There is a central figure here, wearing camouflage-print pants, with pale skin and dark hair, but his torso erupts into a strange, fleshy tangle of disembodied arms and legs. There is no way to tell where he begins and these “others” end. As if we, human bodies and souls, are porous and permeable. As the Beatles crooned in 1967: Life flows on, within you and without you.

Openness and opacity

Snarled in the web of relationships crisscrossing the exhibition, I return to Giada and George. This, too, presents mysteries. The title implies a couple, and the woman, nude, lies back, laughing, in erotic bliss. But aside from, perhaps, the faintest suggestion of a shadowy figure, “George” is nowhere to be seen.

With its large scale, the painting has an imposing presence, as impossible to ignore as another person in the room. And it seems to embody some of the paradoxes of the exhibition. “Giada” exists, but only a few dark lines delineate her figure against the rainbow-sherbert ground. Half of the canvas is covered in black paint, yet the colours show through. The woman is supine, unselfconscious, vulnerable, yet her eyes are painted over, blinds drawn on the windows to the soul. A portrait of both complete openness and complete opacity. We are always individual, but also never alone.

___________________________________

Non c’è Rosa Senza Spine (Ain’t No Roses Without Thorns) runs at LOY Contemporary Art Gallery till 30 May 2025. Learn more at loygallery.com.

Read our previous reviews of LOY Contemporary Art Gallery exhibitions here and here.

Header image: Giada and George (2025), oil, acrylics, and spray paint on canvas, 135 x 170 cm.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

Seven Ways to Spend Your Singapore Art Week 2026