Step into Heman Chong’s solo show at the Singapore Art Museum, and you’ll find yourself in a space full of mysterious objects. There are stacks of cups and books, a sign dourly reading “THIS PAVILION IS STRICTLY FOR COMMUNITY BONDING ACTIVITIES ONLY,” and a single magazine taped, inexplicably, to the wall.

With his sardonic sense of humour and finger-on-the-pulse observations of society, the 48-year-old has become one of Singapore’s most globally circulated contemporary artists, having staged institutional solo exhibitions in China, Germany, the UK, and beyond. But given his longstanding relationship with the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) — beginning with the Nokia Singapore Art exhibition in 1999 and including the 2003 Venice Biennale, which marked an important step for Chong onto the world stage — it’s appropriate that SAM presents the artist’s first major survey.

Featuring 51 works, the show tracks Chong’s practice from the early 2000s to the present, a period that coincides with both his development as an internationally recognised artist and with the spread of the Internet, social media, and other forces shaping our hyperconnected world today. The title itself, This is not a dynamic list and may never be able to satisfy particular standards for completeness, is an appropriated text from Wikipedia, appearing on pages that list everything from famous poets to types of cake — a gesture towards both digital culture and the limits of knowledge.

I’m fortunate to not only see the show, but also get a peek into the installation process, speaking to the artist and to curators Kathleen Ditzig and June Yap across one meandering afternoon. Surrounded by cling-wrapped boxes, rolled-up pieces of vinyl, wet paint signs, and other marks of an exhibition coming into being, they explain to me that Chong has had a hand in every component of the show, from lighting and exhibition design all the way to marketing. In a way, Ditzig suggests, we can read the show itself as an artwork too.

Built environments

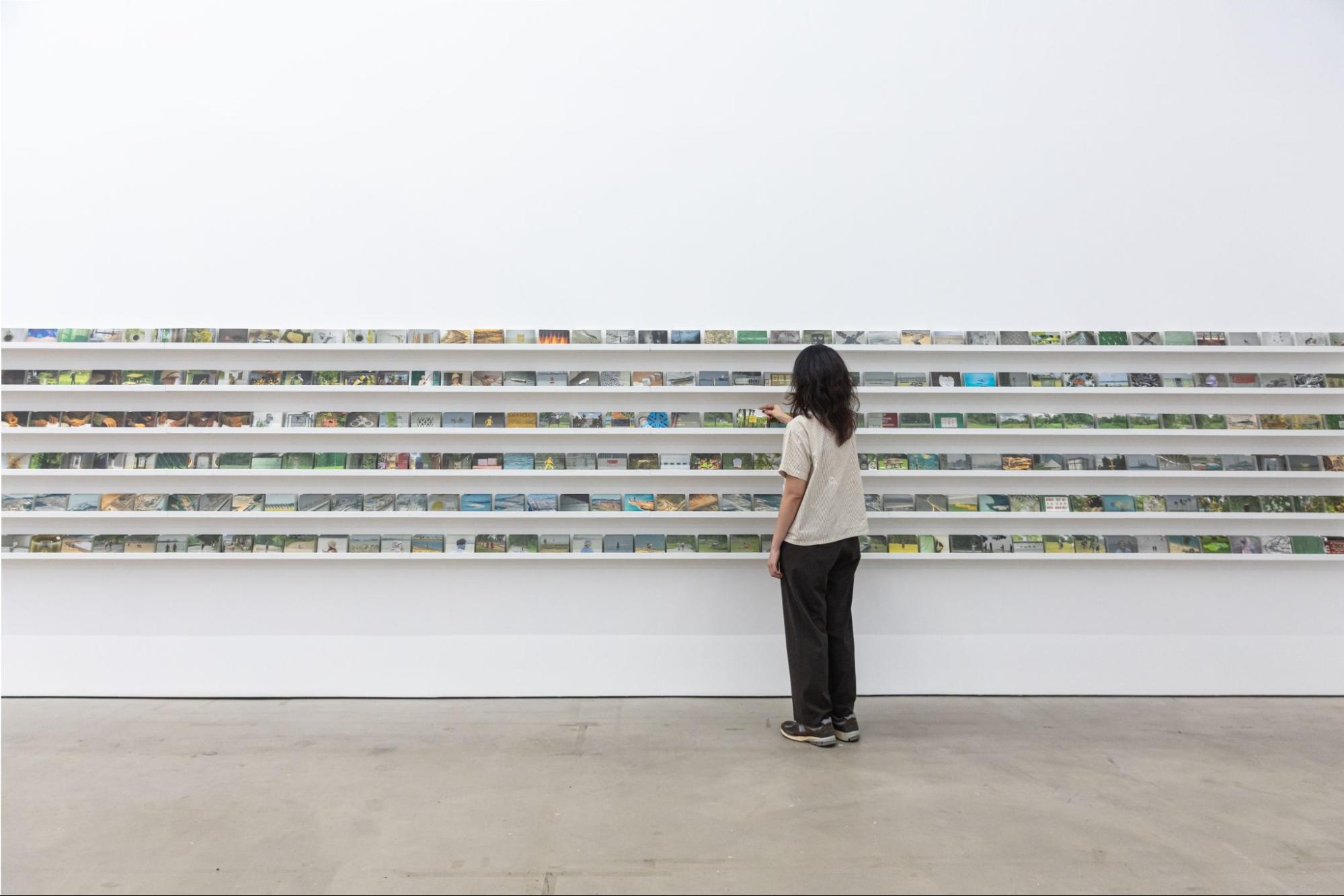

A visitor to This is a dynamic list will soon notice that Chong is fascinated by spaces: public spaces, private spaces, and the thresholds between the two. This is perhaps most apparent in Calendars (2020-2096) — a monumental set of 1,001 photographs, arranged wall-to-wall, which Chong describes as the “heart of the show.” Each photograph depicts a publicly accessible space in Singapore; the bottom row of images nearly touches the ground, while the top row is far above eye level, nearly too high to see.

Walking past the array, I spot museums and libraries, void decks and places of worship, furniture showrooms and nondescript corridors. But all these spaces are severely, eerily empty. There’s a mannequin in a clothing store, and a life-size person-shaped standee, but otherwise human figures are almost nowhere to be found. Chong tells me that he refrained from deliberately clearing each space of passers-by, instead waiting — and putting me in mind of a scrupulously non-interfering wildlife documentarian — for them to empty out on their own.

These spooky spaces are presented as calendar pages spanning a 76-year time frame, decades after the work was incepted in 2004. Looking at them in 2025, five years into the time of Calendars, produces the vertiginous feeling of peering into an alternate timeline or pocket dimension (one which also uncannily forecast the deserted public spaces of the pandemic years).

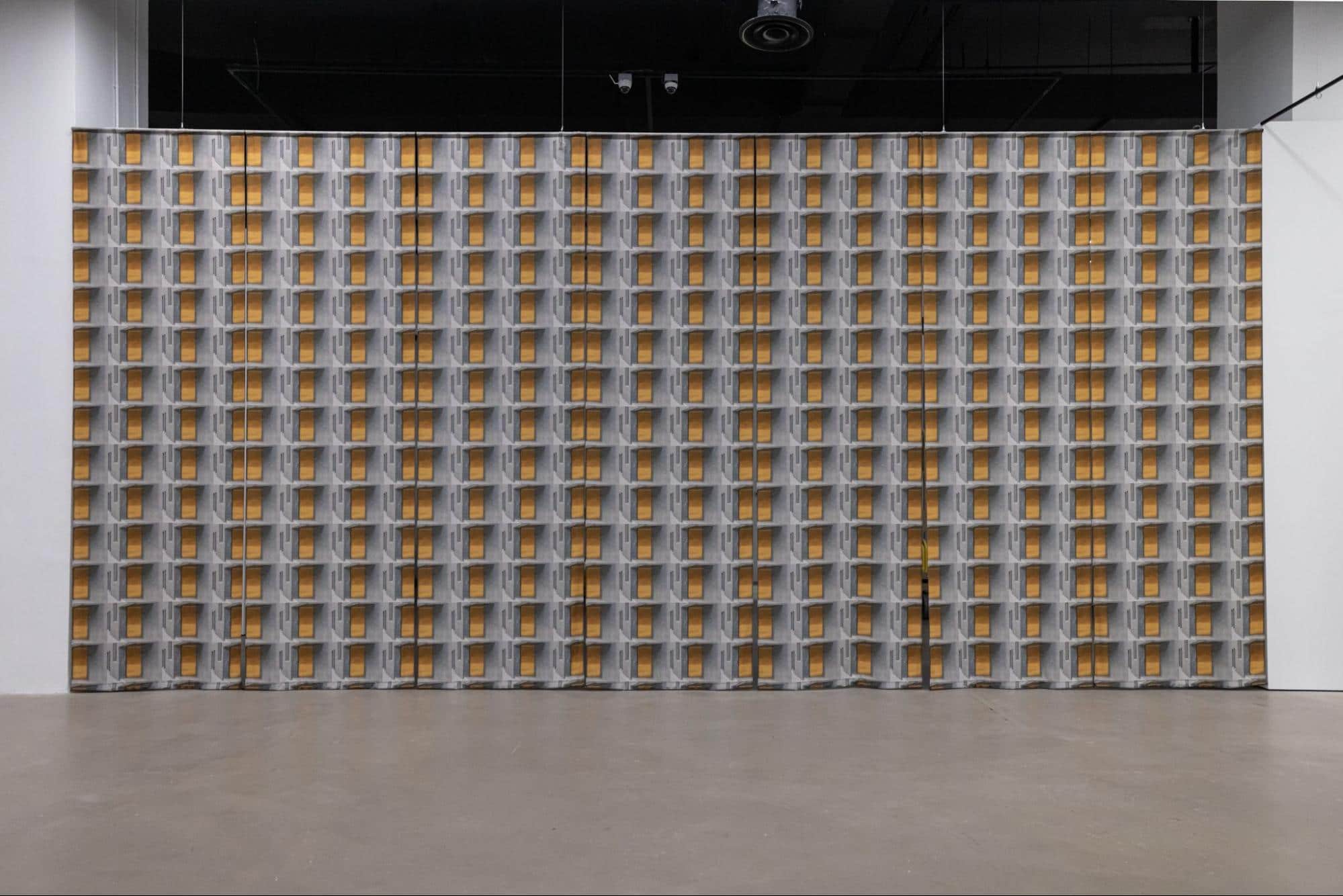

As a work, Calendars helpfully exemplifies several aspects of Chong’s practice: his interest in urban spaces, his tendency to pursue projects over years and years, and a kind of artistic obsessiveness. These leanings surface again in his Foreign Affairs series, in which he photographs embassy back doors. In the exhibition, Foreign Affairs #106 is printed repeatedly on a polyester curtain to form an abstract, geometric pattern. Next to Calendars, these shrouded, inaccessible, high-security sites form a counterpoint to the empty public spaces. Yet, paradoxically, the curtain provides a porous, easily transgressed barrier between the different areas of the show.

For Chong, built spaces are arenas of endless questions and contestations. Portraying them enables him to investigate issues of political power, collective experience, and urban change. “What gets to be shared by people? What gets to be private?” he asks. “What gets to be renovated? What gets to be completely obliterated? These are very big questions in Singapore, because our built environment is constantly being renewed, over and over again.”

In an adjoining room, we browse through shelves of postcards that line the walls, forming a patchwork quilt of images: landscapes, plants, fences, street signs, advertisements, bits of trash. It’s a down-and-dirty miscellany of modern life — 550 individual images (which visitors can purchase) taken as Chong perambulated the edges of Singapore. Once again, a single work gestures towards multiple concerns in his practice, from his use of walking as a method to his interest in forms of communication. “Postcards are the protoype social media,” he points out. “This is how we used to share an image, you know what I mean?”

But Perimeter Walk also illustrates how Chong constantly works with — and against — limits. This particular project is pointedly conscribed by the literal borders of Singapore. But other works strain against the borders of not only space but also time (Calendars), acceptability and control (surreptitiously photographing embassy back doors), knowledge and meaning (blacked-out newspapers, shredded book pages), and memory (performances requiring participants to memorise and retell short stories).

With his many longterm projects, Chong understands this last constraint — the finitude of the human mind and body — perhaps all too well. He concluded Calendars, for instance, because he had pushed both idea and himself to exhaustion. “There are series here,” co-curator June Yap tells me, “which could break people to go through.” To her, this “dogged and determined fashion” in which Chong works makes possible the “fascinating amassing of images and objects” we see in the show.

Everyday systems

Beyond physical sites, Chong is also intensely interested in the intangible systems we use to represent ourselves and relate to others: calendars to structure time, borders to structure space, rules to structure society. At the same time, he points constantly to the limits of these systems — their arbitrary relations to reality and their abstract, even nonsensical qualities.

Paperwork, for instance, comprises 500 A4-sized pieces of rusted iron, arranged in a circle on the floor. By highlighting this standard paper size, Chong also highlights the strangeness of such a standard existing at all — a sheet of paper measures precisely 210 by 297 mm in most countries due to some clever German convention-setters, not any immutable law of the universe. But we agree upon such systems (the length of a week, the spelling of a word, the value of a dollar) because we believe they allow us to communicate ideas, run companies, and govern countries — to make the world go round.

Nearby, the 2009 work Index (Down) consists of 9,600 red triangle stickers applied directly onto the wall. (On stock market ticker displays, an upside-down red triangle signifies that the value of a stock is trending down.) Chong’s only real stipulation for this work was that all 9,600 stickers be installed within a day; arranged at random and placed only as high as a human can reach, the scattered stickers coalesce into forms resembling countries on a map.

Hot on the heels of the 2008 financial crisis, Index (Down) is an abstraction of an abstraction — an artistic interpretation of the stock market, which is itself only a partial representation of the global economy and the infinite complexities of buying, selling, and speculating at scale.

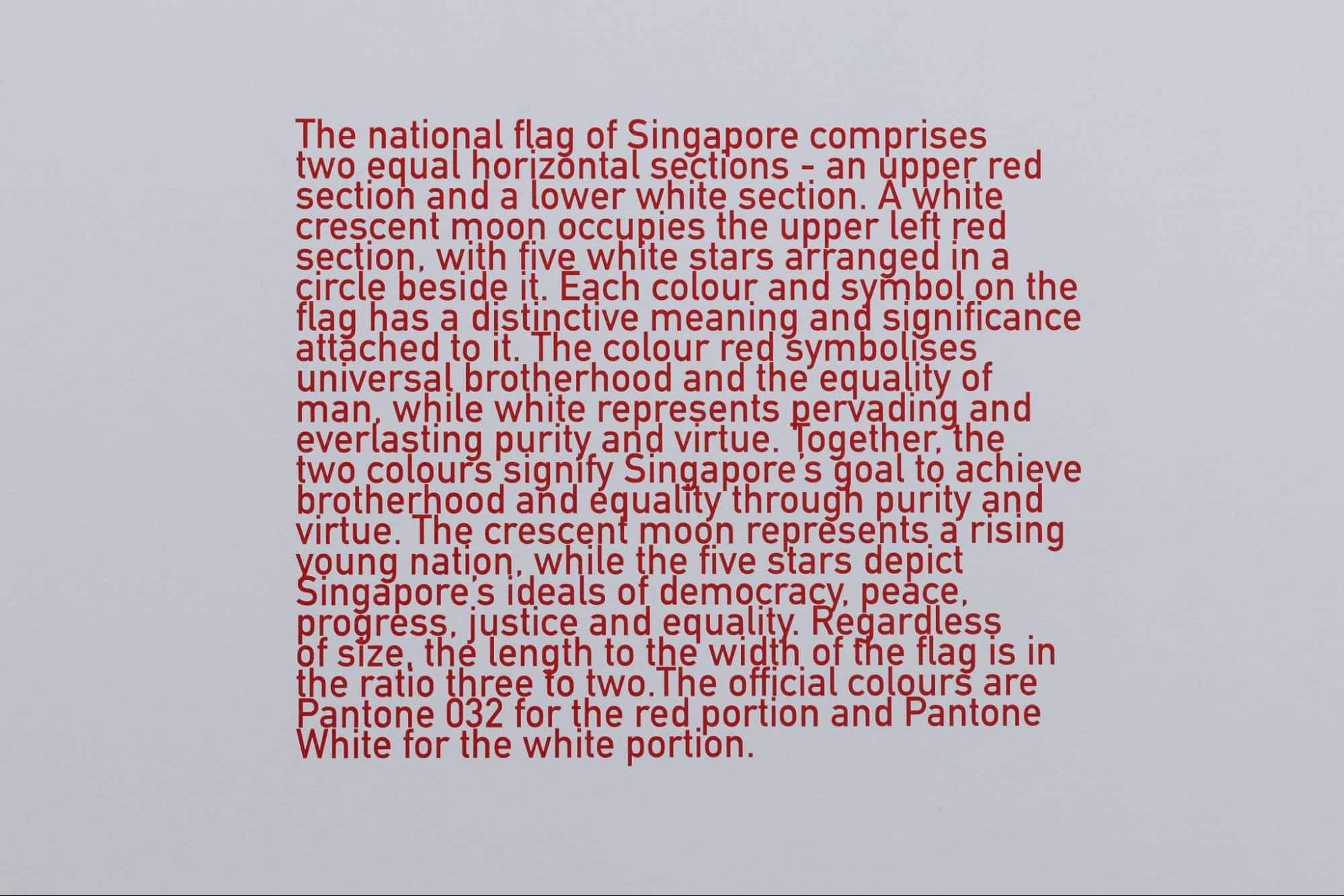

Works like The Singapore Flag and 106B Depot Road Singapore 102106 continue to probe the gaps between concrete reality and abstract imagination. In the former, Chong skirts restrictions on reproducing the Singapore flag by printing a textual description of it on the wall. As I read the text, which details the flag’s two coloured sections and moon-and-stars iconography, the familiar image appears as if by magic in my mind, at once real and unreal.

Similarly, 106B Depot Road is a 3D-printed representation of the public housing in which Chong has lived and worked in for 16 years. The model, however, relies not on precise building specifications but rather on Chong’s verbal description of his home to architect Jiehao Lau — and is hence only as accurate as memory allows.

An exhibition text links 106B Depot Road to the imagined value of public housing assets and the speculative nature of the property market, and thus to what Ditzig identifies as a strong “Singapore-critical” strain in Chong’s work. But the piece also speaks to how information about reality can be distorted when we remember it and communicate it to others. These weird interactions between the tangible and intangible, the real and imagined, and also the physical and digital worlds form some of the most compelling aspects of Chong’s practice.

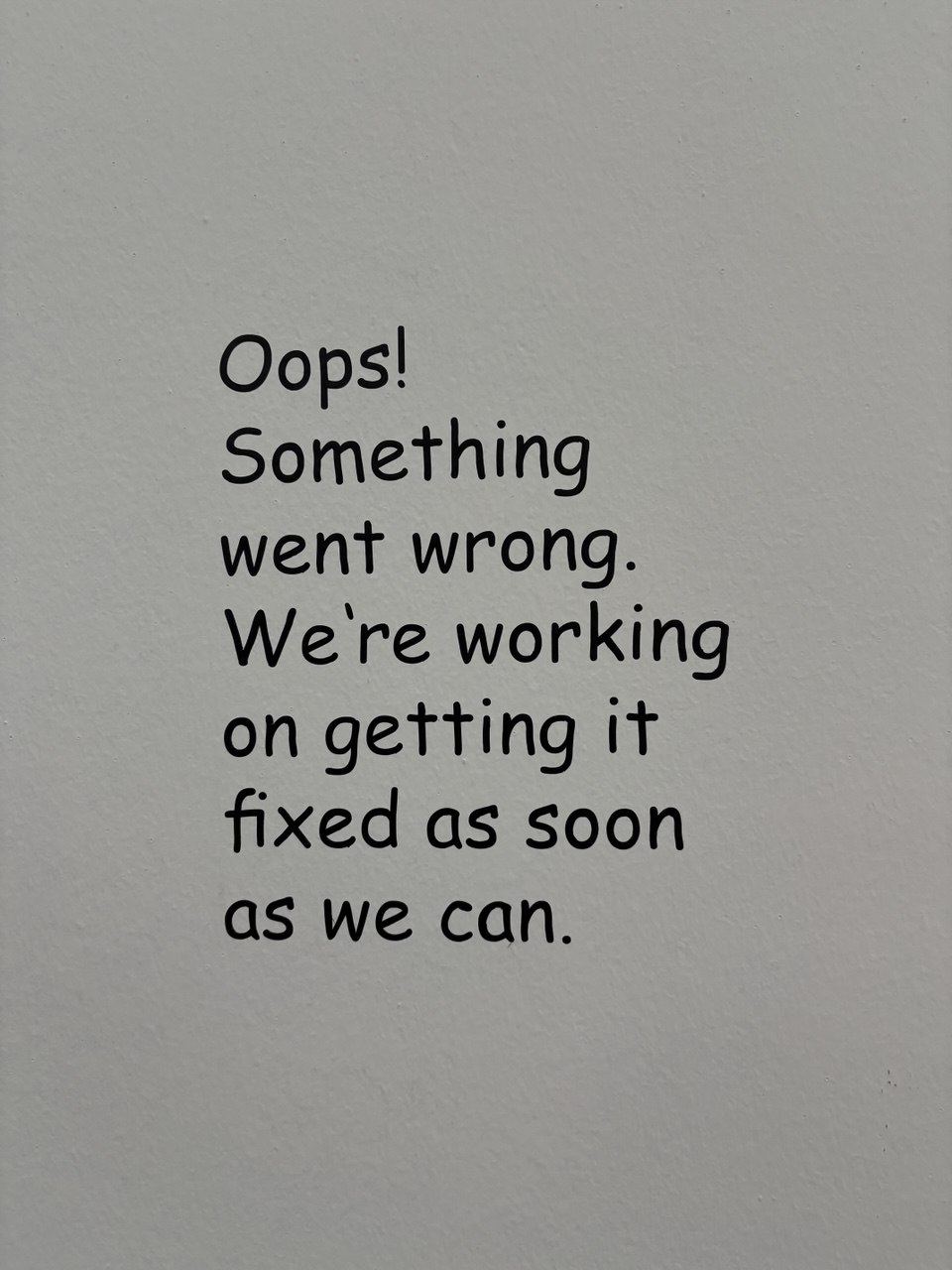

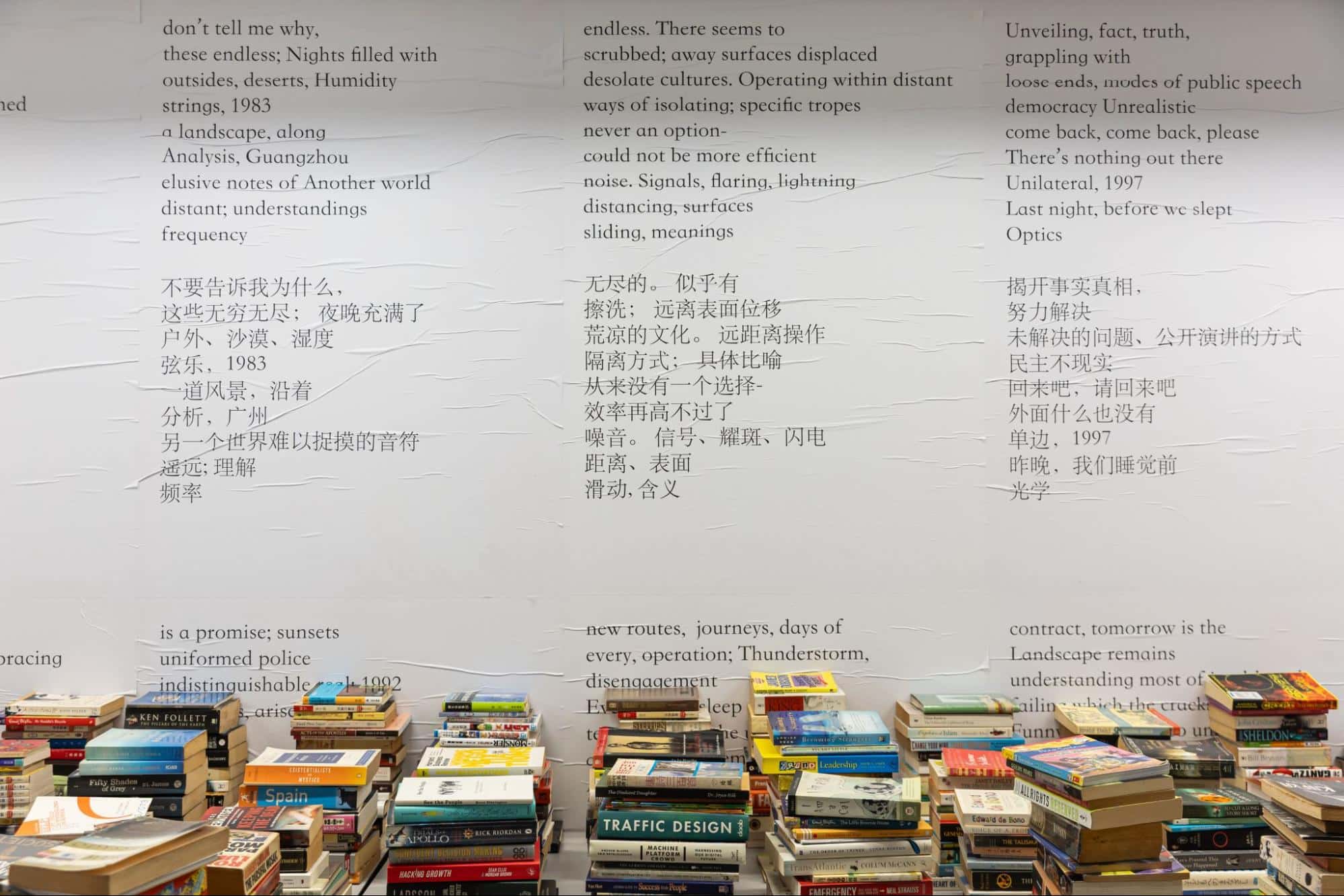

For the digital world — that mysterious, real-yet-unreal forum that may well be the most important site of our 21st century — is another crucial space for the artist, who has variously appropriated error messages, memes, spam emails, and other digital texts in his work. When visitors first enter the exhibition, they will encounter Prospectus: paper posters printed with texts in English and Mandarin and plastered messily onto the walls.

These fragments are all that remain of a novel Chong drafted in 2006 but deleted out of frustration. In 2024, while preparing for the exhibition, Chong went to a data retrieval company, who could only recover 239 of the original 70,000 words — making the text impossible for the viewer to piece into a coherent narrative, and barely recognisable to the artist himself.

Prospectus at once illustrates the entanglement of the digital and physical realms (digital files, stored on a physical hard drive, both of which can decay) and Chong’s characteristic embrace of entropy. Not only has he turned corrupted files into artwork, but he’s also leaned into the slapdash aesthetic of “flyposting,” a poster-pasting technique often used in guerilla marketing and activism, and covered the gallery’s pristine walls with uneven creases and lines. “Even the contractors had a problem when they installed it …” he tells me. “It’s a very national effect, you know? We cannot accept things that are a bit wrong and out of sync.”

Entangled ideas

Surveying Chong’s work, I find myself drawn in by its relationship to representation. When Ditzig describes Chong’s practice in terms of “hyperrealism,” she obviously does not mean that he sets out to literally capture the world as we see it, in the style of a documentary photograph or photorealistic pencil portrait. Rather, she’s talking about its inseparable relationship with life and time, as Chong astutely observes the world, sustains series over several, and rolls with whatever punches fate throws his way. “You work till you collapse, [and] that itself becomes part of the work. Or you work to the point that you destroy a novel, and then it’s whatever chance retrieves for you. These are the literal materials of life.”

Perhaps no work exemplifies this better than Stacks, a series which Chong has been adding to since 2003. Each year, he collects significant books he read and cups he used, stacking them into humble arrangements resembling cairns. “It’s very irritating to live with me, because cups will just keep disappearing,” he quips.

Stacks also clarifies another aspect of Chong’s work, one which perhaps explains why This is not a dynamic list is, at least to me, such a dizzying show. A kind of compression occurs in his work, in which small, modest objects (in this case, books and cups) stand in for much larger concepts (an entire year’s worth of experiences). The same thing happens on a massive scale in The Library of Unread Books, a reference library consisting entirely of donations from viewers. Each book bears the name of its donor, pointing towards a whole unseen lifetime of experiences, bookstore purchases, dwindling shelf space, and abandoned reading goals.

I think of the literary device of synecdoche, in which a part of something is used to refer to the whole. And also, surprisingly, of Renaissance still life paintings, where a butterfly might symbolise transformation, and soap bubbles or a skull the fragility of life. Despite obvious visual differences, Chong’s work is doing something similar, in which a single simple object — a book, an embassy door, or a red triangle — can explode outwards into half a dozen other ideas. Small wonder, then, that a show which sets his works in conversation with each other feels like a Gordian knot, a dense tangle of interconnected thoughts, inextricable from each other, with no clear beginning or end.

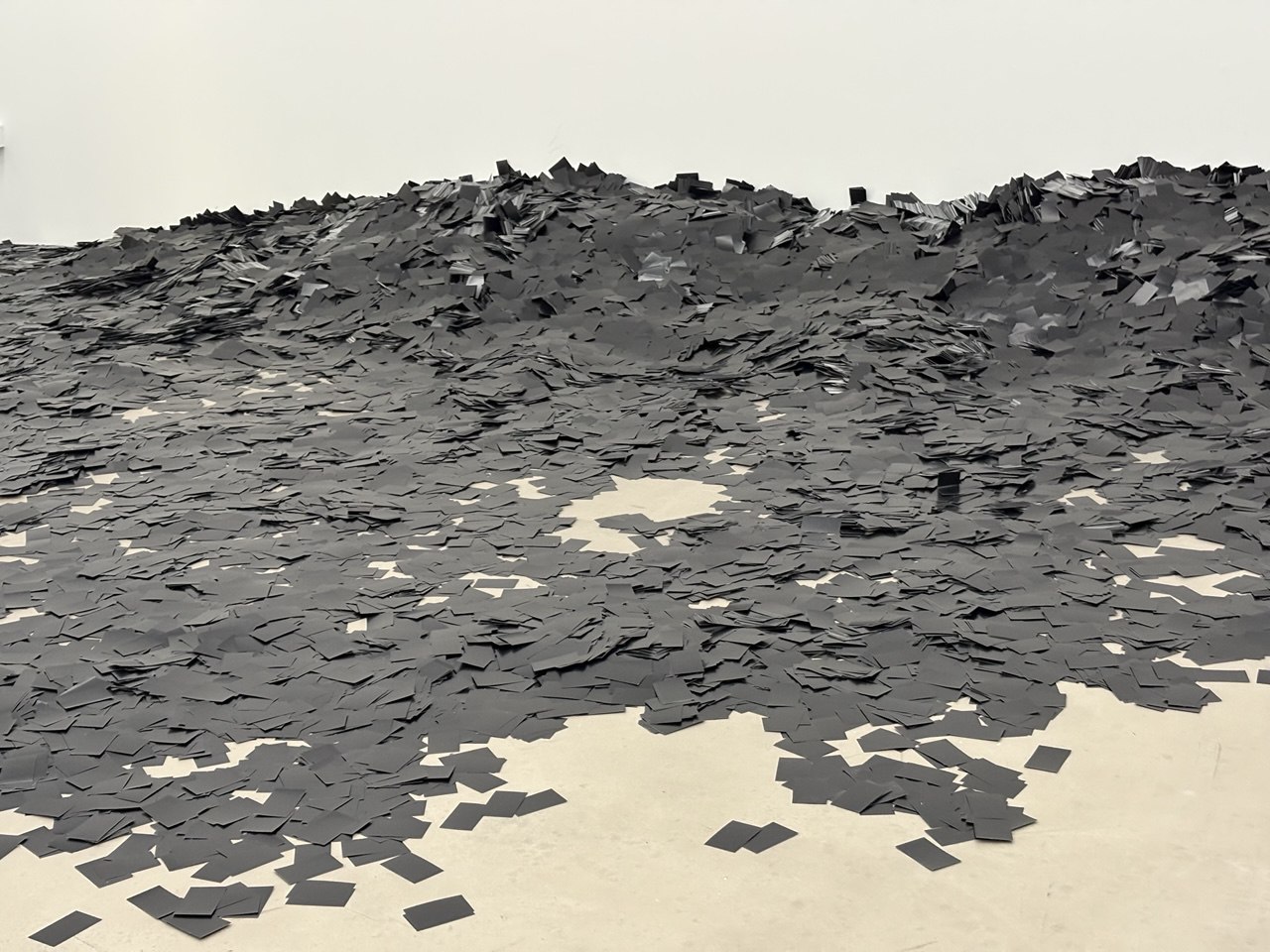

Perhaps to help visitors out of this thicket, the curators have recommended a viewing order for the show, starting with Prospectus and The Library of Unread Books and ending with Monument to the people we’ve conveniently forgotten (I hate you). This pile of one million black business cards suggests the broken professional connections of the 2008 financial crisis, but also represents another strategy that gives Chong’s work its visual impact — accumulation. From donated books and rusted iron sheets to postcards and photographs of Singapore, many of Chong’s projects gain power through profusion. The same could be said of the show itself, where works created across two decades, gathered together, acquire new meanings through their interactions with each other.

But as complex as This is not a dynamic list is, the curators push back against my suggestion that Chong’s work — which has often been interpreted through the lens of conceptualism, an 20th-century art movement which prized not art objects but their underlying ideas — might be difficult for some viewers to understand. Yap points out that Chong uses simple, everyday images and activities, like postcards, while Ditzig adds that conceptual art, due to its emphasis on personal interpretation, could even be seen as a lower-barrier form of art. Citing Chong’s YouTube channel Ambient Walking (which has over 25,000 subscribers), she dubs his approach a kind of “popular conceptualism.”

“I think he makes conceptualism friendly, actually,” Yap says. “Conceptualism can be a lot harder than this.”

I wonder if the forces of accumulation in Chong’s work, as well as the interdependent, machine-like ways in which various components interact, might apply not just to the artworks but to the visitors as well. Through their responses — their book donations, conversations, and social media posts — visiting masses are enfolded into the system of the exhibition. The whole relying on the parts, and the parts relying on the whole.

___________________________________

This is a dynamic list and may never be able to satisfy particular standards for completeness runs till 17 August 2025 at SAM at Tanjong Pagar Distripark. Visit singaporeartmuseum.sg to find out more.

Header image: Installation view of Perimeter Walk.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

When the Mekong Flows Into a Michigan Museum

Seven Ways to Spend Your Singapore Art Week 2026