How do we listen to, read, and witness migrant voices, and empathise better with them? Migration may be a bureaucratic process, but the process is also at once deeply personal, potentially painful, and often a vehicle of collective trauma.

At the exhibition Between Lands: Migration as Transformation, held at the Goethe-Institut Singapore in early October, seven Southeast Asian artists sought to answer this question through the deeply personal works that they created in response to this fraught experience.

Each wall in the exhibition’s tight space was lined with artworks that teemed with stories — memories from Bui Cong Khanh, Justin Loke, Jakkai Siributr, Jason Lim, Yadanar Win, Nge Lay, and Aung Ko. These artists tussled with their personal histories within our region and beyond, exploring the themes of trauma, displacement, natural decay, and embodied memory.

As part of the Sub+ Youth Curators Programme by arts nonprofit The Substation, final-year Nanyang Technological University (NTU) undergraduates Goh Cheng Hao, Phyllis Chan, and Foo Wee San curated this show, with the guidance of their advisor Dr. Iola Lenzi.

For this story, we chatted about the importance of this exhibition within our current zeitgeist and how curation can be a mode of compassion.

Migration in the Singapore context

This exhibition is one of many local shows in the past few years that dissect the theme of migration. But why migration, and why now?

The curators suggest that migration matters because most Singaporeans are migrants too — a fact we often forget. “We feel stable in our national identity,” Goh notes, “but when we consider our ancestry and origins, those labels become less certain. We’re not so different from those who have recently arrived.”

In fact, Chan adds that her curatorial experience has made her consider more closely what it means to be Chinese in Singapore. She reflects: “For me, the exhibition comes from a rather personal place that has made me more conscious of my position as a descendant of migrants. I have observed how these cultures brought over have changed and been adapted to fit into local contexts, and this became a departure point for me in thinking about the exhibition.”

As we pride ourselves on living in a melting pot of cultures, we should be embracing the malleability and porosity of cultures, instead of retreating into ever-narrowing echo chambers. A recent CNA article points out the stark lack of interaction between Singaporeans and the migrant workers here. It notes how despite there being over a million migrant workers in the city state, there are few meaningful opportunities to integrate them into local communities. This in turn breeds local anxieties about “cultural erosion,” among other fears.

But what of the fears and anxieties of migrants themselves? Exhibitions such as Between Lands offer a poignant counterpoint, illuminating how migration is lived, felt, and endured from the other side of this divide.

Looking further afield, Foo points out how migration also shows up as a pressing global concern in examples such as the decades-long genocide in Palestine. In the October 18 “No Kings” protests in the United States, millions gathered to oppose President Trump’s policies, his insidious immigration crackdowns among them. Migration tends to be discussed as a bureaucratic issue, but how often do we actually think about those who have faced the exhausting and life-changing consequences of migration? This exhibition suggests that the answer is: not nearly enough.

On reading and witnessing migrant voices

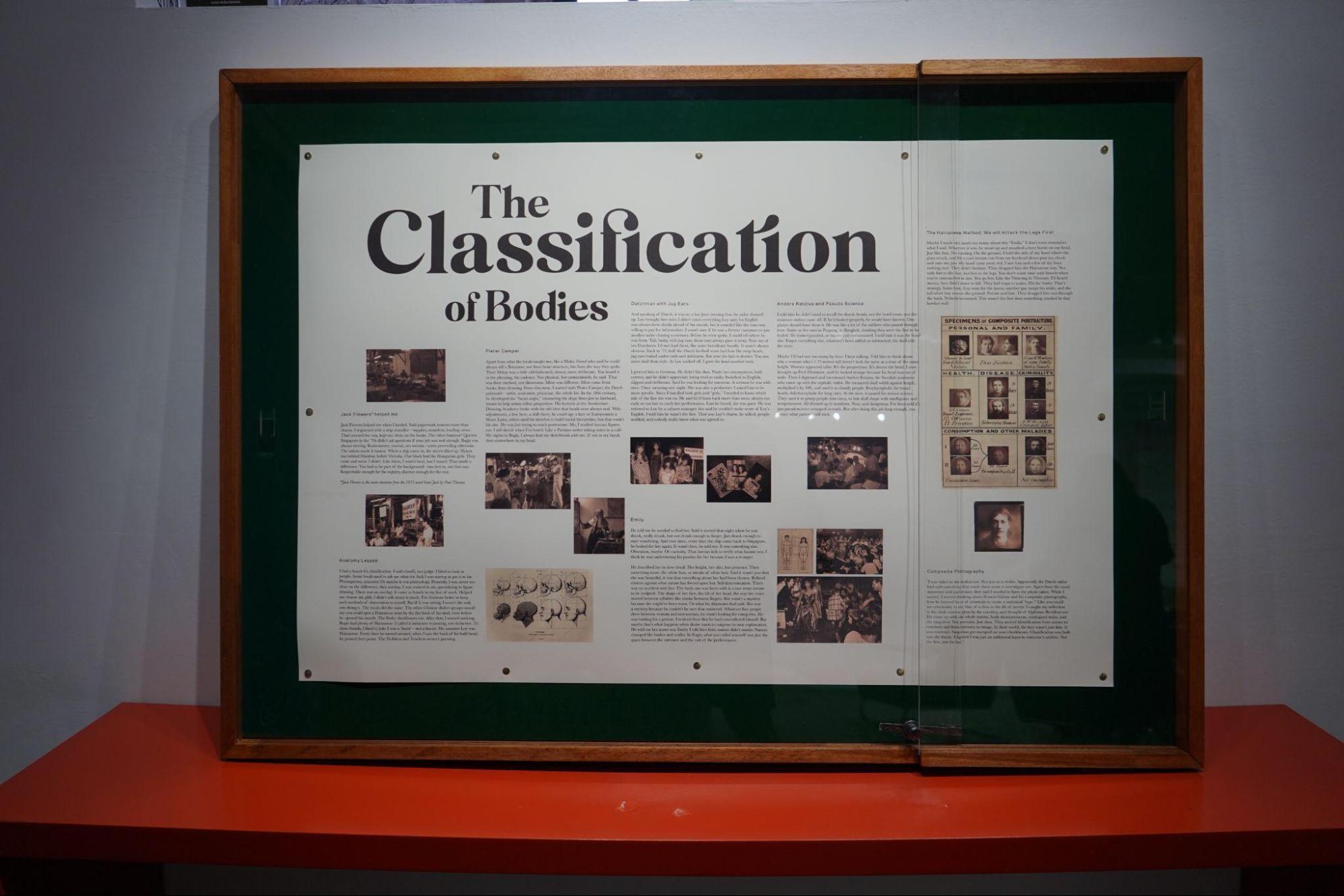

Between Lands championed the embodied act of reading and witnessing migrant voices through its presentation of interactive artworks. Works within the exhibition often contrasted the laborious experience of physically moving across lands with the intangibility and ineffability of memories and cultural heritage left behind.

For instance, Singaporean artist Jason Lim’s 2011 photographic series Study with landscape features the artist donning a moss-sewn mask as he stands against different natural landscapes, blending into the flora and fauna around him. While the set of photographs was conceptualised and made during Lim’s residency at France’s Fondation la Roche Jacquelin, the terrain is not clearly recognisable as French. Instead, attention is drawn to the body language of the artist as he points, stands, and walks within these ambiguous landscapes.

Such emphasis on the physical body mirrors the labour of assimilating into new, unfamiliar surroundings. It also excavates the rigorous psychological assimilation that one must simultaneously undertake, as the lack of people or identifiable monuments within the landscapes highlights the intrinsic loneliness that migrants feel while experiencing life-changing moves.

Goh comments that artworks like these articulate the nuances of the migrant experience and are “subjective gestures to memory and loss.” “These representations are always going to be approximate and never fully distilled in all their complexity.” This might mean that they elude being fully understood, but, as Chan adds, “at the end of the day, the audiences must respond to the work based on [their] own histories, beliefs, and philosophies.”

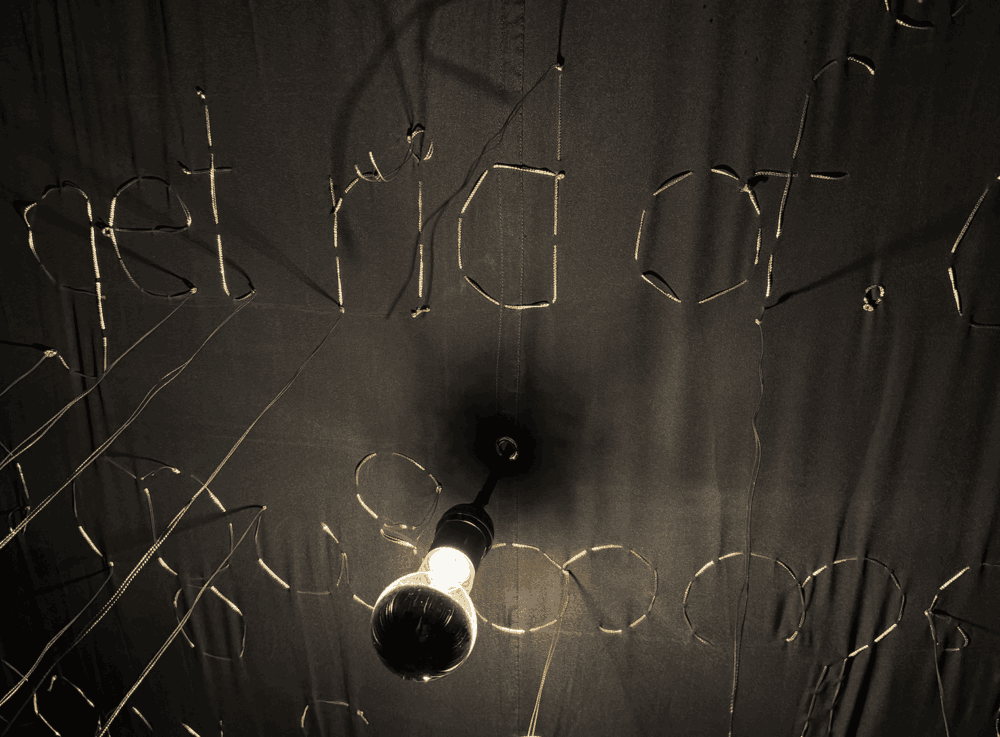

When audiences engage with works like these, they are drawn towards empathy. In Nge Lay’s Phantasma Concha (HOME 5), visitors are invited to enter a warmly-lit black tent, where gold threads on the roof detail the migrant experience of being on the move. They lie on rattan mats and read these embroidered words in English, Burmese, Chinese, and more.

In this work, the act of reading in a communal space allows the audience to bear witness and find resonance between their personal experiences and the testimonies shared, as well as to extend this connection and conversation to those inhabiting the space with them.

Beyond text, Aung Ko’s and Yadanar Win’s video works feature soundscapes reminiscent of Myanmar, the artists’ country of origin. Visitors to Between Lands could listen to Yadanar Win’s poem recitation of “Precept of Life” by Burmese revolutionary poet Khet Thi, which details how to hold onto hope throughout a revolution, or to the melodic lapping of ocean waves in Aung Ko’s parents’ village in Thuye’dan, Myanmar, as the artist captured the fading traditional craft of bamboo raft-making.

Curating and art as modes of care

The works in Between Lands function as translations of memory, history, and culture, positioning the curators as caretakers of the artists’ lived experiences and emotional vulnerability, rather than distant intermediaries. This approach runs counter to the traditional notion of the curator as a detached mediator.

“We shouldn’t see artworks as perfect conclusions,” Chan reflects, “but as imperfect and evolving, much like the people behind them.” In this spirit, the trio eschew the idea of curatorial distance altogether, favouring instead a warmer, more generous mode of collaboration. The resulting exhibition resisted fixed narratives, allowing migrant identities to remain unsettled and perpetually in motion.

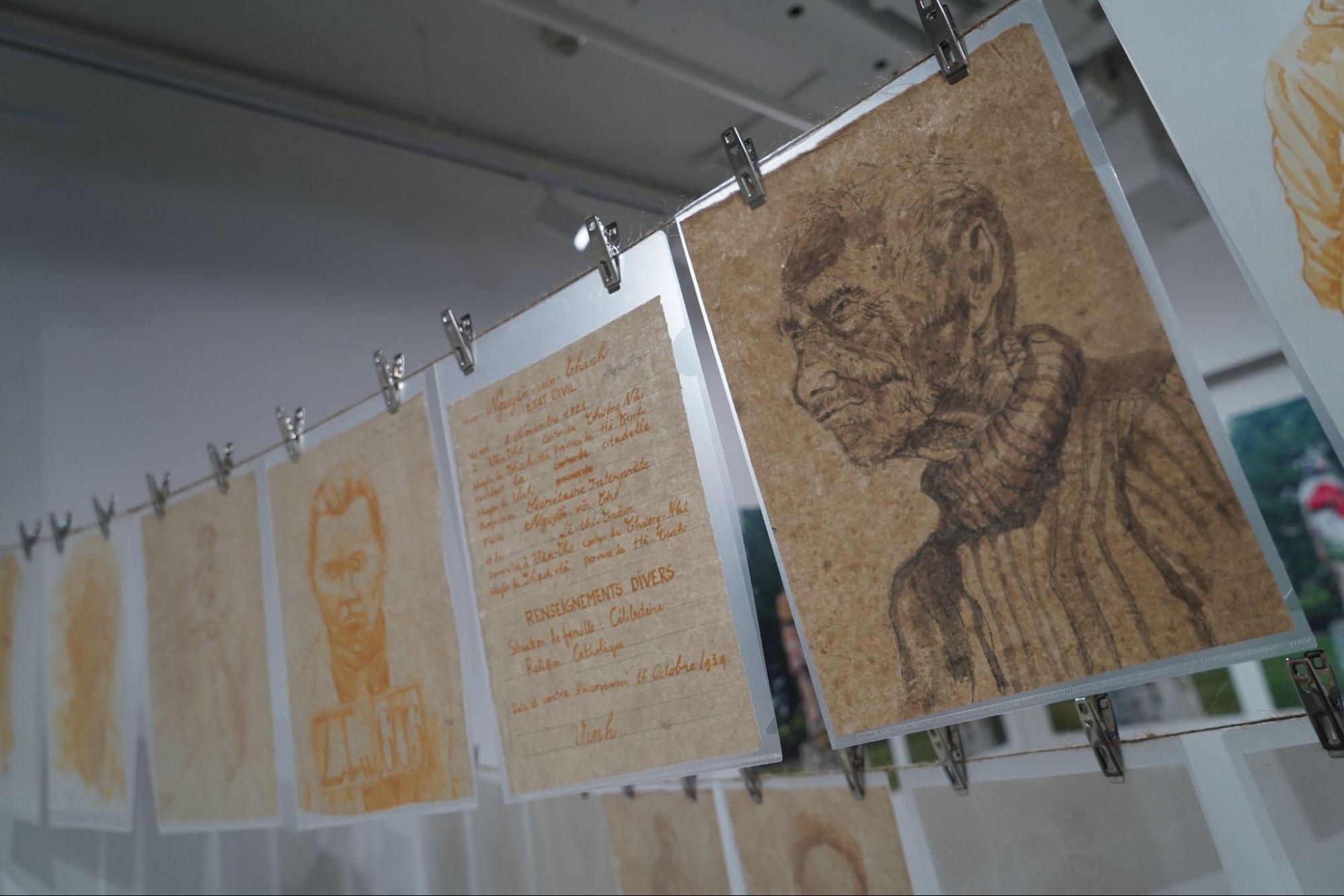

This approach was made tangible through the response of a Vietnamese visitor, who felt deeply seen in Bui Cong Khanh’s works. Speaking to the artist in their shared mother tongue, she recognised in his pieces the frustration and emotional complexity of navigating estrangement from one’s homeland. For the curators, this moment affirmed the exhibition’s emotional resonance — art became a site where migrant experiences were not only represented, but viscerally recognised.

So, how do we listen to, read, and witness migrant voices more responsibly? Between Lands suggests that the answer lies not in easy empathy or clarity, but in staying with discomfort — with stories that refuse neat resolution, memories that remain fragmented, and identities that resist being made legible.

Rather than offering migration as a theme to be understood, the exhibition positioned it as an ongoing condition: embodied, unstable, and unresolved. Through intimate gestures — lying beneath embroidered testimonies, hearing waves from a distant village, piecing together colonial archives — audiences were asked not only to observe, but also to slow down and recognise their own distance from the experiences presented.

In this sense, the curators’ role was not to translate migrant pain into palatable narratives, but to create a space where these complexities remained intact. Between Lands does not promise reconciliation; instead, it insists on attentive witnessing — and on the ethical responsibility of looking, listening, and remembering.

___________________________________

Between Lands: Migration as Transformation ran from 4 to 12 October 2025 at the Goethe-Institut Singapore and was co-presented by The Substation and the Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF).

Header image: Exhibition view of Between Lands: Migration as Transformation. Image by Naoko Kaneda.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

When the Mekong Flows Into a Michigan Museum

Seven Ways to Spend Your Singapore Art Week 2026