People who know me from my time in LASALLE’s art histories masters programme will know that I have been fangirling for the longest time over Sabahan contemporary artist Yee I-Lann. Here’s a work that I somehow never got to write up in a term paper or thesis, present at a conference, or even post on Plural’s social media feed, even though it is one of my favourites among the many works of Yee’s that I love. Come to think of it, there is no place that I’d rather share it than right here on our website, so perhaps it’s just as well that I never got to do this before!

First, a little background for those among you who might not be familiar with the artist. Yee I-Lann’s artistic practice focuses primarily on photo-media, although to call her an artist-photographer would be misleading. Yee uses photographic images, her own, or images culled from archives and other sources, and carefully stitches various fragments of such images into highly-contextualized composites, which she has presented in a wide and innovative range of formats, including on batik, porcelain plates and the ubiquitous Selangor pewter commemorative plates, to name just a few.

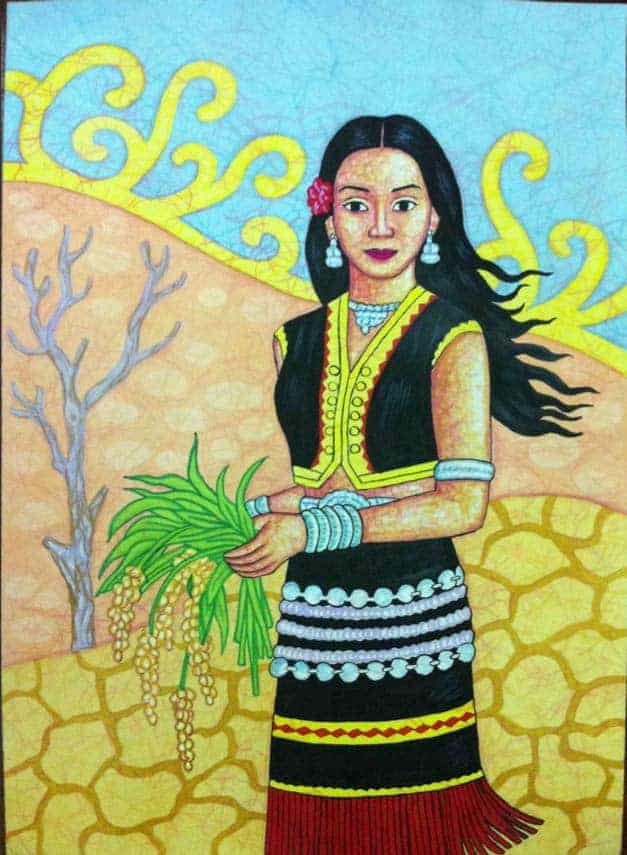

While Yee is a Malaysian citizen, she is, first and foremost, a proud and fiercely loyal Sabahan – her pride in and love for the place of her birth so vividly palpable in many of her works, like this one, Huminodun, part of a series of three works in her Kinabalu series.

The legend of Huminodun is the Kadazan-Dusun creation myth or origin story in which Kiniongan, the Creator, sacrificed his only daughter Ponompuan (who became the spirit of the paddy, Huminodun) to save mankind from famine, her body parts divided and planted to grow various crops, primarily rice. Huminodun’s sacrifice is celebrated by the community every year during the Harvest Festival in Sabah.

In Yee’s work, the mythical deity is presented as a fecund woman (the model is the artist’s sister, I-Ling), standing in an arid and damaged landscape. This work, like the others in the series, is a lament for Sabah, its rainforests and rice paddies cleared to make way for oil palm estates, often owned by large national corporations. Indigenous communities have been displaced from their lands and lost their traditional way of life, suffering worsening poverty even as revenue from the land is redirected away from Borneo to Peninsular Malaysia and the federal government, with little of it used to improve infrastructure within the state or to help the local population.

Mount Kinabalu, which appears in all three images [in the series], the only fixture in Sabah’s dramatically changing environment, is the compass to Kadazan-Dusun communities and the final resting place of ancestors. Monsoon clouds grow thick in the land below the wind. A storm is brewing. The Kinabalu series is my lament for Sabah.

Yee I-Lann