Indelible Marks Peels Back Layers of Colonial History in Australia and Singapore

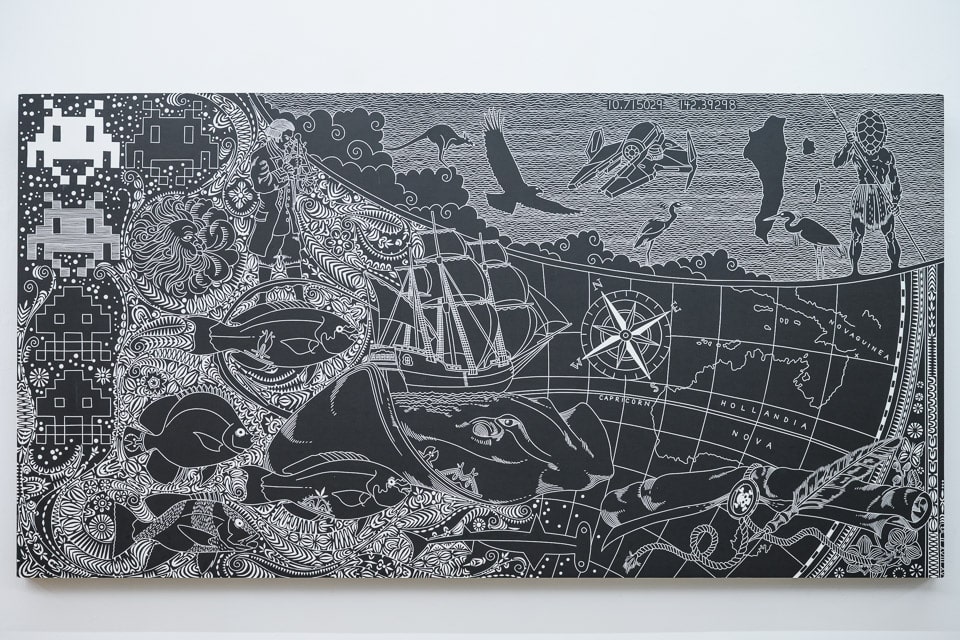

Measuring over a metre in length, Brian Robinson’s imposing linocut print Bedhan Lag: Land of the Kaiwalagal brims with swimming sea creatures, swirling botanical patterns, roiling waves, and curling clouds. Through three different sets of imagery, the piece narrates the layered histories of Zenadh Kes/the Torres Strait, an island-dotted waterway between Australia and Papua New Guinea.

On one side of the composition, animal and vegetable motifs reference the rich ecology of the Torres Strait Islands, as well as tales of the zugubal — shapeshifting ancestral spirits inhabiting the sky, sea, and land — which Robinson (of the Maluyligal, Wuthati, and Dayak peoples) learned as a child. A figure wearing a turtle-shell mask represents the Kaurareg people, who live on Bedhan Lag/Possession Island, the point from which the British laid claim to Australia’s East Coast, to this day.

Ship, compass, map, sailor with sextant, and skull-and-crossbones scroll signal the arrival of colonisers, laying the path for centuries of violence, slavery, erasure, and abuse. Lastly, aliens from Space Invaders and a spacecraft from Star Wars frame, in Robinson’s words, “colonisation as something that repeats across time — new invasions, new empire, new technologies — all woven into a shared visual language that audiences recognise.”

Bedhan Lag is one of the first works viewers see in Indelible Marks, a month-long exhibition at Art Seasons Gallery telling stories of colonisation and resilience from Australia and Singapore. Co-organised by Tyrown Waigana (Indigenous Australian), Desmond Mah, and Nazerul Ben-Dzulkefli (both Singaporean-Australian), the seven-artist exhibition identifies both differences and affinities in how the two nations have responded to their colonial pasts — bringing awareness to irreversible harms while celebrating the continued survival of indigenous cultures and identities.

The exhibition opens with Robinson’s Odyssey: Colonial Encounters in Zenadth Kes: 8-bit shapes of alien and spaceship, cut from plastic and spray-painted in electric orange, red, and turquoise hues. Traditional patterns and glitching pixels overlap with piles of skulls and the jutting-out silhouettes of seafaring vessels. From the jump, Robinson’s multilayered work inducts us into the exhibition’s key concerns: the overlapping histories in this region of the world, the clashes of cultures that still define us today. Something that always lies beneath.

Truth-telling through art

Indelible Marks continues with four digital prints by Tyrown Waigana (of the Wadandi Noongar and Ait Koedal peoples). Two feature bold graphic figures in black, white, and purple against bright pink grounds, which Waigana imagines as “eternal entities that exist forever and in some realm we can’t begin to comprehend.” A looped pair of pale arms pierces Enter Face Ethel’s head, while overlapping triangle shapes and interlocking limbs form the body of Heavy Bottom John.

With their exaggerated movements and cartoony expressions, Waigana’s characters exude a sense of joyful whimsy. But these lighthearted, humorous aesthetics belie troubled histories — the prints are inspired by visuals from the Carrolup Collection, a body of work by Aboriginal children stolen from their families and forced to assimilate into settler culture in the 1940s.

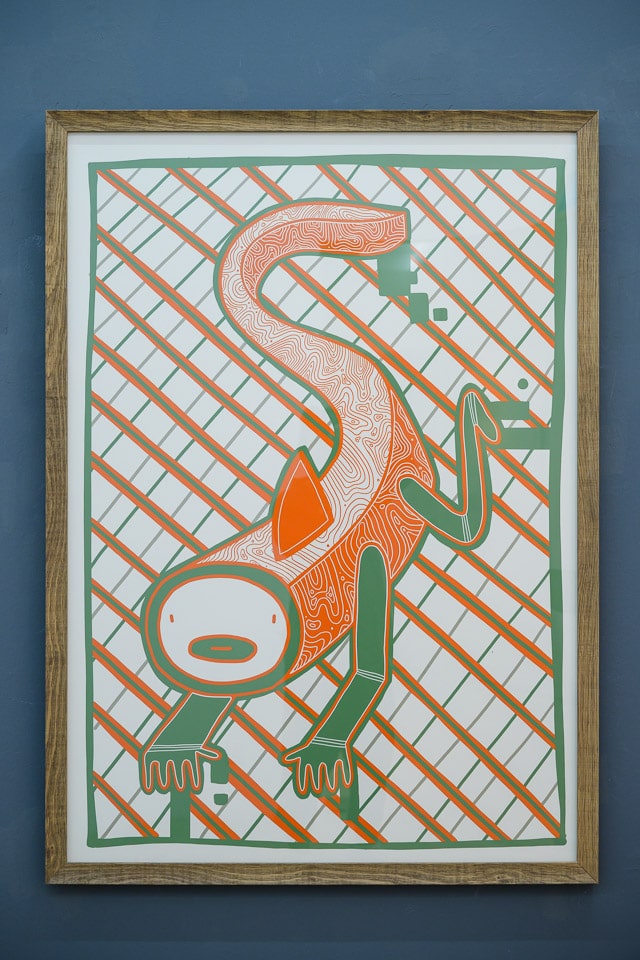

In Flop Drop and Shark Legs, four-legged fish-men flail against netlike patterns in green and orange hues. These images emerge from Waigana’s fascination with the occurrence of hybrid fish creatures across different cultures, as well as his awareness of the various traps — addictive algorithms, capitalist overconsumption, systemic oppression — that await contemporary individuals. Caught in traps with no exit, the panicking fish-men are ensnared by vast forces beyond their control.

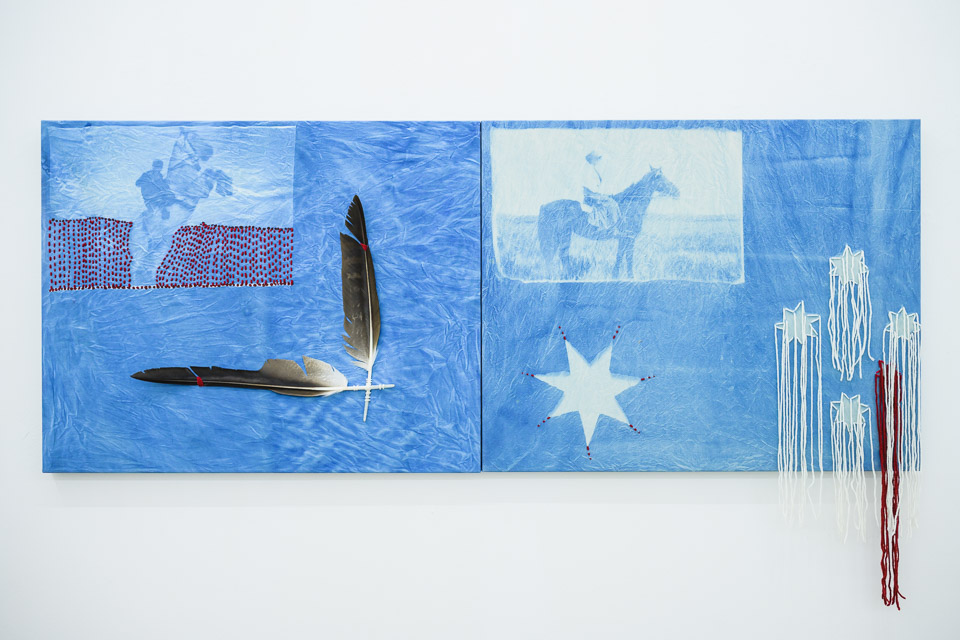

Like Robinson’s works, Ilona McGuire’s textured blue dipytch Bound By Blood carries a complex assortment of symbols. Two parallel images of people on horseback emphasise that Australian history has two sides: on the one hand, McGuire’s grandfather, expelled from school, working on a farm, his wages withheld. On the other, a settler woman from the Macpherson family, a Scottish clan known for establishing the town of Carnamah.

The “Southern Cross” symbol on the diptych’s right side is both an icon of Australian national identity and a constellation which McGuire’s Noongar and Kungarakan ancestors would have known since time immemorial. White threads point to the labourers who built the Australian wool industry; red ones evoke violence and bloodshed. Eagle feathers scavenged from roadkill gesture towards the technological changes wrought by modernity.

Even McGuire’s chosen medium of cyanotype, an early photographic method that relies on exposing desired images to the sun, bears symbolic meaning. As the artist, keen to look beyond the surface of a stereotypically laid-back, beer-and-Vegemite-guzzling country, explains: “The act of ‘exposing’ mirrors the act of ‘truth-telling’ about Australia’s shared history.”

Confronting colonial legacies

And what of Singapore? As the exhibition text and essay point out, Australia and Singapore take dramatically different approaches to their colonial histories. In Australia, decades of massacres, forced removal, and other human rights abuses are rightfully seen as a shameful blight on the nation’s past, with a long history of Aboriginal political activism continuing into the present day.

Singapore, conversely, tends to celebrate its colonial era — see landmarks like the Raffles Hotel, Raffles Institution, and Raffles City shopping centre, all named for the colonist Stamford Raffles — while glossing over painful histories of economic exploitation, geographical displacement, and cultural loss. But as Indelible Marks shows, this certainly isn’t true of everyone. Like their Australian counterparts, Singaporean and diasporic artists are also using art to hold these histories to the light and recover lost parts of their identities.

Two paintings by Desmond Mah directly confront the spectre of Raffles, often uncritically lauded as the founder of modern Singapore despite having spent limited time on the island (especially compared with his appointee and administrator William Farquhar). In Dear Right Honourable Lord Hastings, Mah crops an 1816 portrait of Raffles and gives him a quill to, as the artwork description reads, “inscribe his disdain onto the skull of William Farquhar.” The artist here employs his signature three-dimensional painting technique to full effect, making it appear as though spooling threads are peeling off Raffles’ body to expose his hollow face and skeletal hands. Like the Wizard of Oz, unveiled as a humbug and fraud, the portrait reveals that our visions of the past are shakily constructed, sometimes out of little more than air.

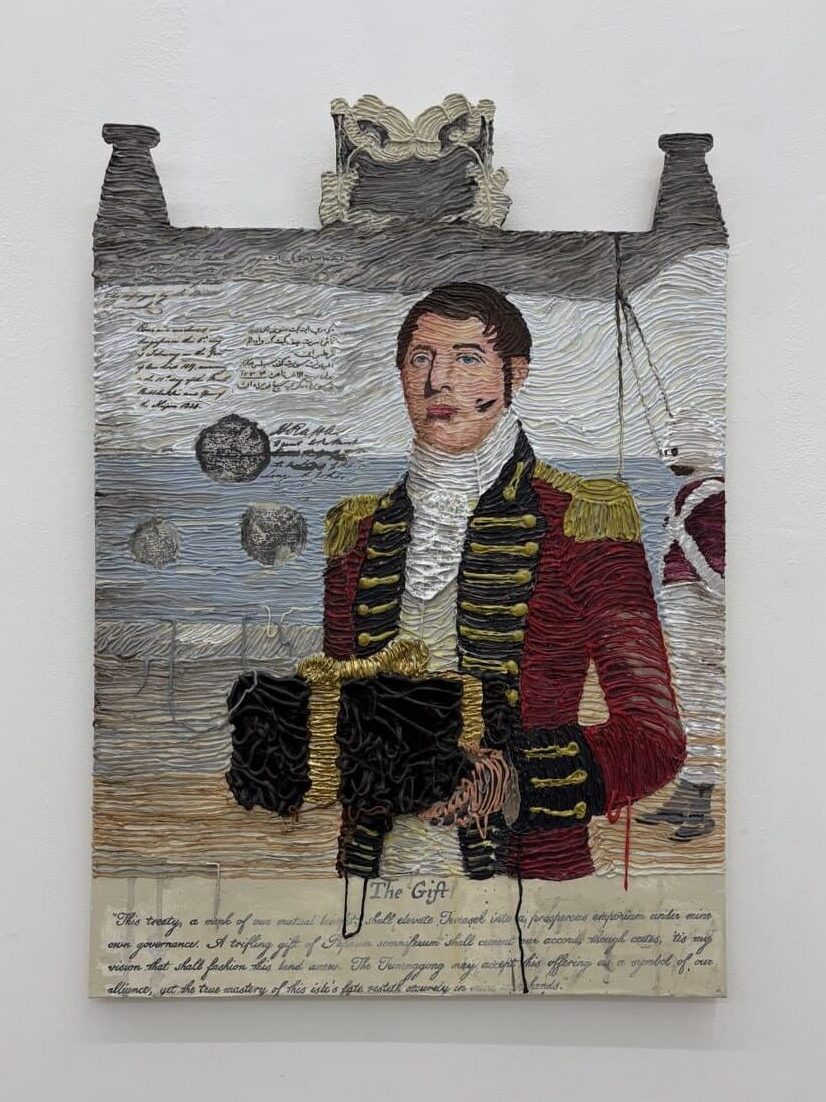

Mah deploys the same effect on Raffles’ cheek in The Gift and jams in even more loaded imagery: an Indian sepoy (infantry soldier) from the British East India Company, scripts from the treaty giving the British ownership of Singapore, and two shapes at the top of the canvas resembling chess pieces or UFOs — expressing, he explains, “the way colonial encounters often appear both strategic and otherworldly.”

Ripples of the past

Alya Rahmat’s two-metre-wide diptych Wealth of the Wealthy Springs from the Poverty of the Poor overwrites the colonial botanical sketch — a seemingly innocous art form, in reality used to extract resources from the colonies — with local batik traditions. In one fell swoop, she simultaneously questions colonial exploitation, gender expectations, and contemporary national narratives.

Like McGuire’s Bound by Blood, the work sets two images in opposition. On the left, Singapore’s national flower is coldly dissected and surrounded by generic floral patterns pulled from tourist imagery. The kepala (head) section of the batik contains a stripped-bare version of the symbolic Tumpal motif, expressing how “traditional methods and knowledge are often disregarded and delegitimized to make way for the idolisation of western knowledge structures, yet still exploited when deemed fit for profit and capital.”

On the right, the jatung pisang (banana flower), flanked by tough, wild-growing lalang, blooms under crudely drawn versions of the Singapore flag’s five stars. In contrast to the Vanda Miss Joaquim, the jatung pisang — typically associated with the mythical Pontianak, a vampiric “fallen woman” — is pictured as fruitful, flourishing, and whole.

For his circle canvases overlaid with Jawi script, Ezzam Rahman takes a slightly different tack from the other artists on show, focusing not only on Western but also Eastern cultural dominance. The widespread use of English as a working language aside, Singaporean Malays (along with speakers of several other Southeast Asian languages) use the Arabic-based Jawi as a written script due to the spread of Islam throughout the region. Tanah Air / Homeland and Tumpah Darah / Bloodshed emerge from Ezzam’s quest to relearn — and learn the history of — the script he learned as a child.

Sampling just some of the layers, like language, ethnicity, and the (racialised) body, that make up our manifold identities, the works call to mind Petri dishes — an oddly scientific analogy that gels surprisingly well with Ezzam’s continued interest in the body, decay, and mortality. Crinkled leather remnants, salvaged from a previous performance, set off all sorts of meaningful associations, resembling a topographic map, the ridges of fingerprints, or even the folds of mitochondria in a cell. Finally, used anti-inflammatory plasters symbolise the painful yet necessary process of healing.

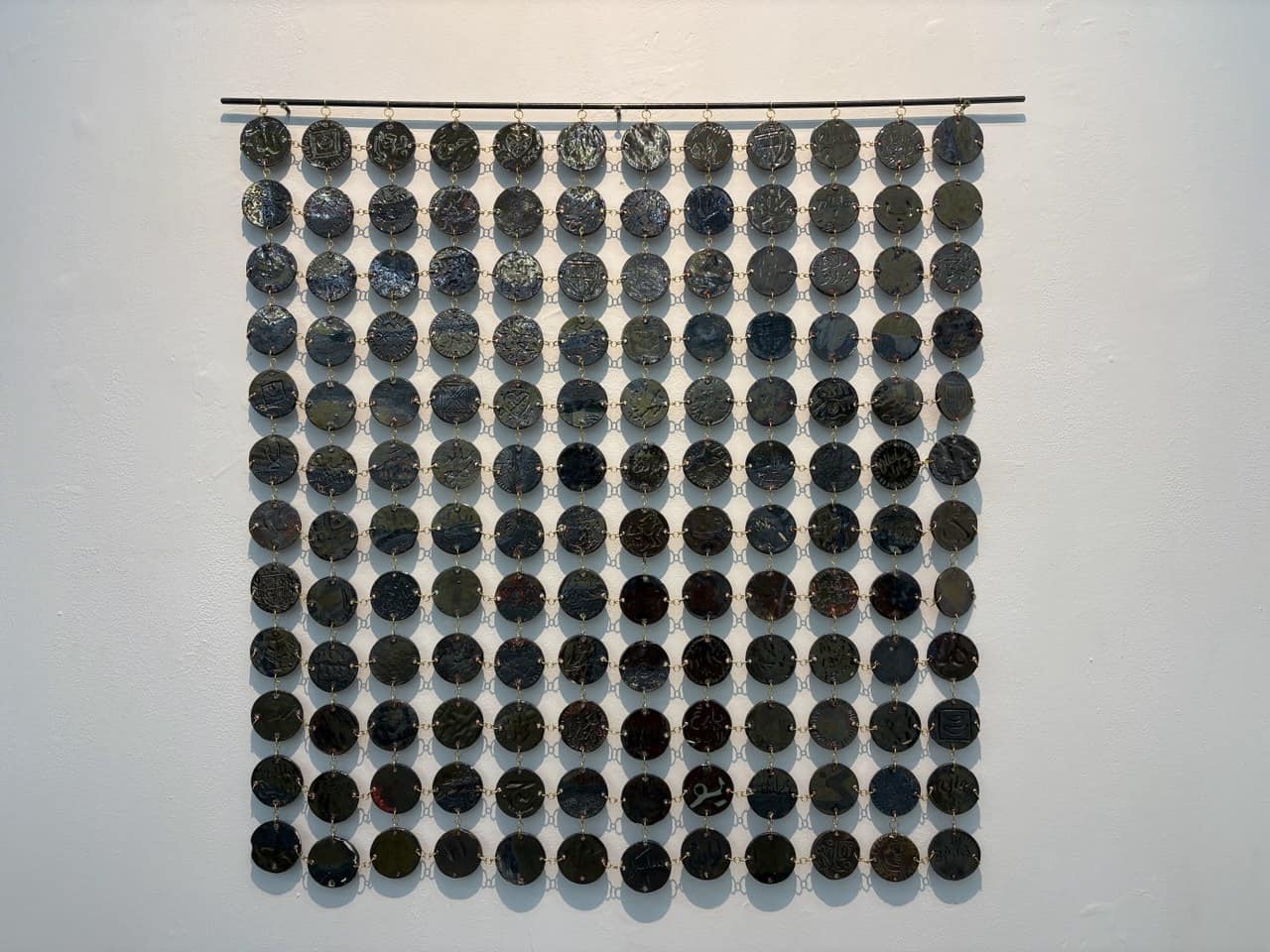

At times, a gentle clinking sound punctuates the exhibition. It comes from Nazerul Ben-Dzulkefli’s Shackled Economies, a curtain of small ceramic circles joined by golden jump rings. Glazed in shades of dark green and brown, the discs are inscribed with symbols from historical coins of both European and local origin as well as words from two Malay narrative poems. The gold rings signify the links between maritime communities — the trade networks disrupted when the British East India Company and foreign merchants edged out the Malay and Bugis traders of the area.

Nazerul, a Singaporean Malay-Javanese migrant to Perth, sees clay as a medium which ties him to his heritage: “tanah air,” the Malay term for homeland, literally means “earth and water.” As Shackled Economies sways, it ripples like the ocean’s surface, its soft chimes recalling the sound of money changing hands — an echo of forgotten trade histories in the region.

Though rich and multilayered, Indelible Marks is not without shortcomings. In the space itself, exhibition text is sparse, which means that many symbolic details and historical references will be lost on the casual viewer. While the free exhibition catalogue ameloriates this, I still found that many of the works’ hidden meanings only came to light through email or in-person conversations with the artists themselves.

But if explained adequately, the exhibition is a powerful cross-cultural representation of what it means to exist in the wake of the past — a source of both pain and pride.

As some of the artists expressed to me, constructing cultural identity in a postcolonial context can be an extraordinarily difficult task. Waigana, for instance, recounted: “Growing up, there were times I wanted to detach from my identity because sometimes it felt like a blessing, and sometimes it felt like a curse.”

Indelible Marks weighs both feelings, but — by celebrating creativity, resilience, resistance, and survival — comes down on the side of joy.

___________________________________

Indelible Marks runs at Art Seasons Gallery till 19 October 2025. Follow @artseasonssg and @desmondmah_ on Instagram for more.

Read our review of the National Gallery Singapore’s 2022 exhibition Ever Present: First Peoples Art of Australia, a reference point for Indelible Marks, here.

Header image: The co-organisers of Indelible Marks. Left to right: Tyrown Waigana, Desmond Mah, and Nazerul Ben-Dzulkefli.

This article is produced in paid partnership with the Department of Creative Industries, Tourism and Sport, Western Australia. Thank you for supporting the institutions that support Plural.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

When the Mekong Flows Into a Michigan Museum

Seven Ways to Spend Your Singapore Art Week 2026