For many Singaporeans, Taiwan feels familiar through shared tastes in food and shopping, a common language, and a similar urban sensibility. Yet, beyond these surface affinities lies a less-examined kinship. What kinds of historical and artistic connections have shaped these two island societies — and why have they been so rarely considered in tandem?

Showing at artcommune gallery from 17 January to 15 February 2026, Mirror Straits ponders this topic in a groundbreaking comparative survey of eight well-known Taiwanese and Singaporean artists active from the twentieth century on. Jointly organised by Singapore’s artcommune gallery and Taipei’s Liang Gallery, the show is notable not only as a rare collaboration between private galleries, but also because there have been few exhibitions, even in museum contexts, which set up a conversation between the historical trajectories of Taiwanese and Singaporean modern art.

The exhibition is curated by Taiwanese independent curator Nobuo Takamori, chief curator of the 2021 Asian Art Biennial and the 2025 Green Island Biennial. His research practice focuses on situating Taiwanese art within wider regional conversations.

Appraising the two societies, Takamori says, “Taiwan and Singapore are both geopolitically significant tropical islands, and they share … a high level of economic development; a population in which ethnic Chinese form the majority while multiculturalism is actively emphasised; and historical experiences shaped by different forms of colonialism, through which distinct social characteristics emerged.”

“Yet, despite this broadly similar historical framework, the two islands ultimately followed markedly different historical trajectories. As a result, their artistic expressions reveal both affinities and divergences in form, sensibility, and approach. Intuitively, I feel that [Singapore] resembles Taiwan as a kind of parallel world, a parallel history: we are of the same people, yet we arrived at different choices.”

Coining the term Mirror Straits, Takamori suggests that Taiwan is culturally closer to Singapore than the other societies of Southeast Asia, and that this proximity allows audiences on both sides to more readily grasp each other’s artistic intentions and strategies.

Takamori adopts a two-part structure for this show, using World War II as a historical hinge between the early artists and the next generation. For the prewar period, Taiwanese masters Chen Cheng-Po and Yang San-Lang feature alongside Singaporean pioneer artists Cheong Soo Pieng and Chen Wen Hsi. Printmaker Liao Shiou-Ping and abstract painter Lee Chung-Chung continue pushing the envelope in Taiwan’s postwar era, contemporaries to Singapore’s Lim Tze Peng and Wong Keen.

Taken together, these artists’ works reveal moments of resonance alongside divergence. They are shaped by a shared cultural inheritance and encounters with Western modernism, yet equally by individual artistic inquiries and local civic contexts.

Mirror Straits resists oversimplified narratives of national style. Instead, the exhibition positions these eight practices as a constellation of voices shaped by historical circumstance, transregional exchange, and individual expression. Takamori’s accompanying essay provides a crucial framework, situating each artist’s practice within its geopolitical moment without flattening differences.

Titans of their respective art canons

If one were to examine the four prewar artists, two shared traits emerge: a commitment to bridging Eastern and Western painting traditions, and an active role in shaping their respective artistic ecosystems through mentorship or institution-building.

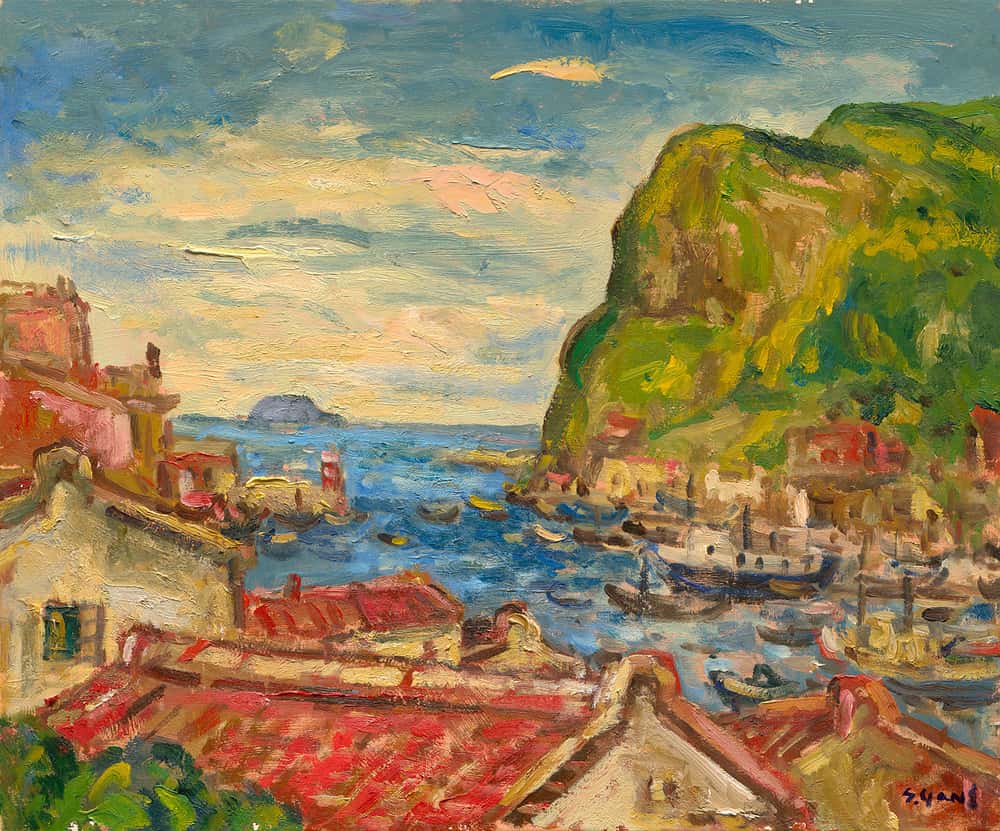

Chen Cheng-Po and Yang San-Lang produced much of their work while Taiwan was under Japanese colonial rule between 1895–1945. Chen is widely considered Taiwan’s first Western-style painter, while Yang was influenced by French Impressionists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Claude Monet during his education in France. For both artists, modern art became a language through which to articulate an emerging local identity.

Chen is considered a titan of the Taiwanese art canon. Blending Chinese ink painting principles with bold colour and Western compositional techniques, he captured the emotional texture of everyday Taiwanese life and set the standard for modern art in Taiwan.

His artistic legacy is inseparable from his political fate. After years of prolific artistic production and civic involvement, he was killed during the February 28 Incident, a violent anti-government uprising in 1947. As Takamori notes, “for the people of Taiwan, Chen is not only a prewar master who pursued the modernisation of Taiwanese art, but also a symbol of the painful historical memories embedded in Taiwan’s quest for self-identity.”

Yet, Chen’s significance extends far beyond the circumstances of his death. Together with Yang and a few other first-generation Taiwanese artists, he co-founded the Tai-Yang Art Association, Taiwan’s largest and oldest non-governmental arts organisation. It was — and remains — a vital platform for local artists, irrevocably shaping the trajectory of Taiwanese modern art.

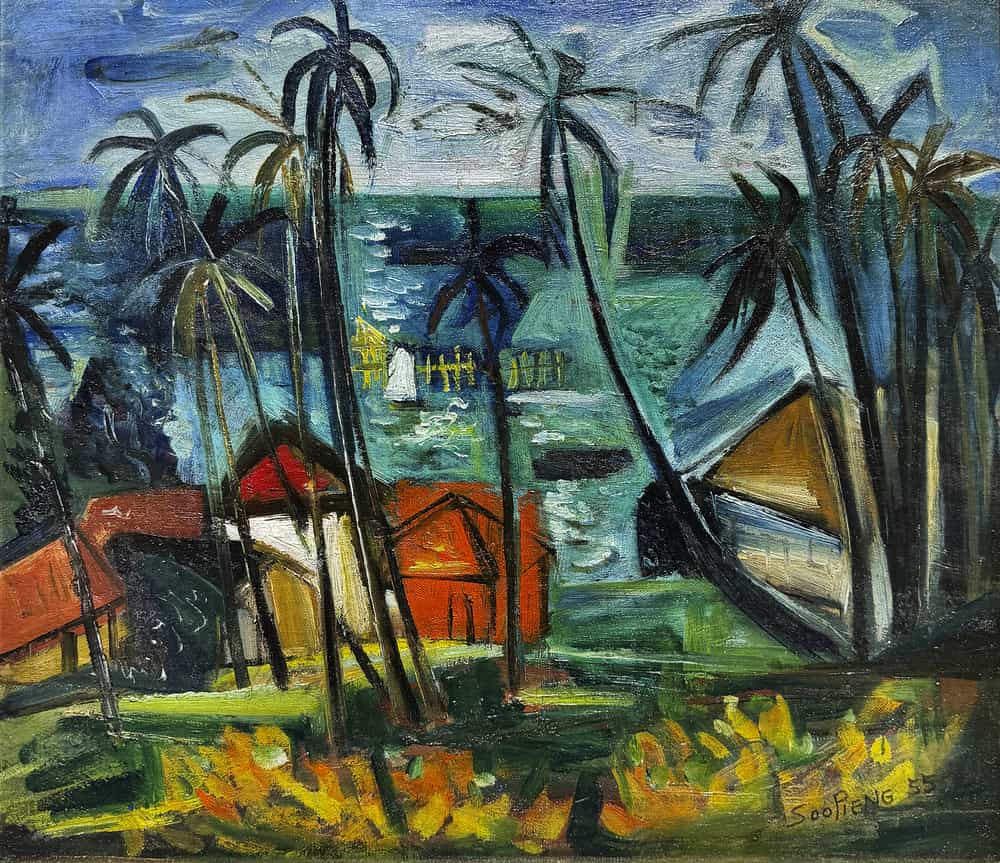

Chen and Yang’s contemporaries Chen Wen Hsi and Cheong Soo Pieng played similar formative roles in Singapore’s artistic development. Both taught at the Chinese High School and the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts — two institutions which turned out some of the nation’s finest artists — and are widely recognised as key figures in the development of the Nanyang Style, which drew from the visual traditions of both East and West.

In Kampong by the Sea (1955), Cheong, like his peers Chen and Yang, borrows from Western styles of treating shape and colour to depict local life. Rather than the Impressionists, however, he more clearly references the School of Paris — notably the movements Fauvism, Expressionism, and Cubism — to develop his pastoral scene.

Taken together, the works of these four artists reveal how early encounters with Western modernism were adapted and reworked within local contexts rather than simply adopted wholesale.

Postwar divergences into abstraction

If the prewar artists negotiated modernity through stylised representation, the postwar set confronted it through abstraction and rupture from visible reality. In Taiwan, the end of 50 years of Japanese colonial rule in 1945 was marked by political upheaval and decades of authoritarian governance under martial law. Artistic expression during this period often turned inward or towards abstraction as a means of articulating what could not be directly spoken.

Across both Taiwan and Singapore, abstraction emerged as a shared response to postwar conditions, enabling artists to negotiate cultural inheritances, ideological constraints, and the accelerating pace of modern life.

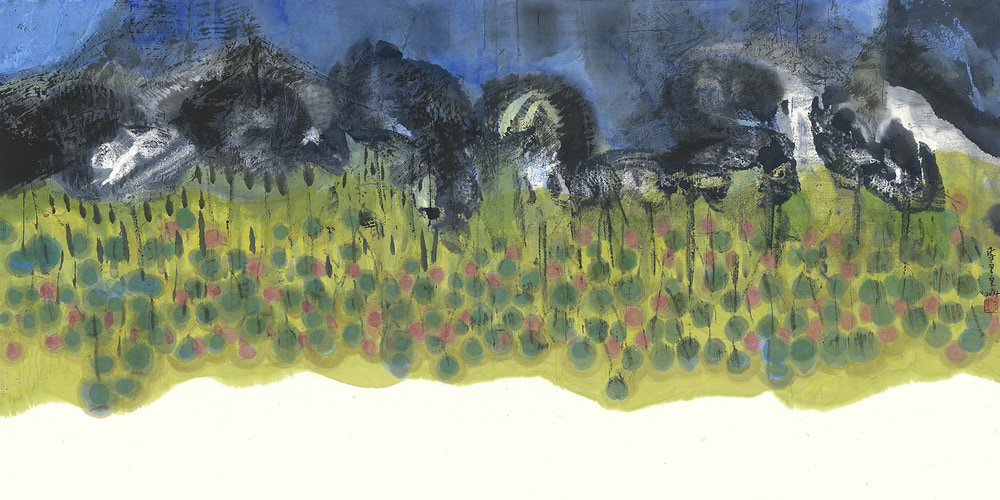

Taiwanese abstract painter Lee Chung-Chung’s delicate ink wash paintings exemplify this approach. Retaining the expressive sensibilities of ink painting while abandoning figuration, her works move this venerable tradition into a fully abstract register, marrying East Asian aesthetics with the avant-garde. Simultaneously, her background in graphic design and oil painting informs her vivid palette and ease in adopting strategies from a range of artistic vocabularies.

In Singapore, Wong Keen’s practice follows a parallel though less restrained trajectory that veers between abstraction and figuration. Brought up in a Chinese literati environment and trained in both Western and Chinese painting under Chen Wen Hsi, Wong left Singapore in 1961 to study at the Art Students League of New York. His work — which translates familiar forms like lotuses, human figures, and even meat into expressive, forceful compositions — reflects the influence of five decades living in the United States and a cultural identity shaped by East-West hybridity.

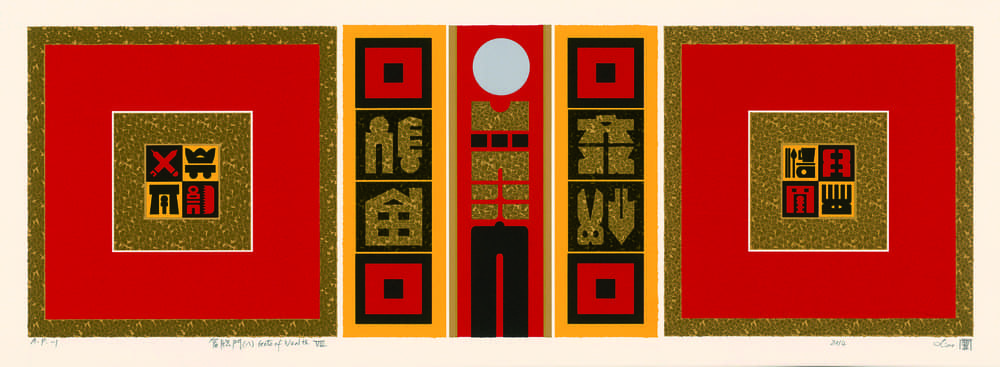

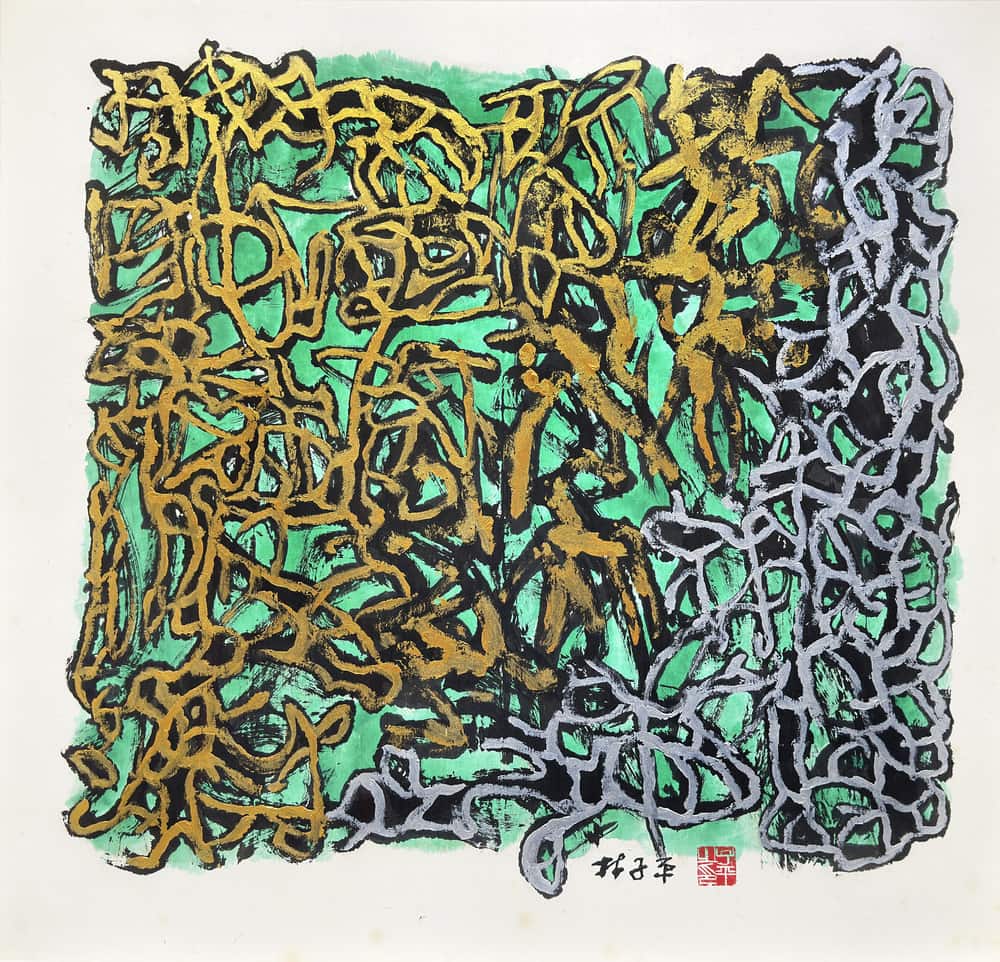

As for Taiwanese printmaker Liao Shiou-Ping and Singaporean painter Lim Tze Peng, both also began with inherited traditions — Chinese characters and calligraphy, respectively — which they each treated as raw material for experimentation.

Widely regarded as the “father of modern Taiwanese printmaking,” Liao constructs a personal visual language from traditional motifs and colour palettes, assembling them into dense, cosmological compositions.

Lim’s self-titled style of “muddled calligraphy” (糊涂字) pushes language towards illegibility. His calligraphic strokes hover on the very edge of meaning, turning characters meant for communication into energetic, gestural forms that resemble gnarled tree roots more than any intelligible writing system.

Seen together, these four postwar practices complicate any misplaced notion of a singular modern Asian aesthetic. While emerging from similar cultural roots, the artists’ explorations diverge in exuberantly multifarious ways.

What Mirror Straits ultimately foregrounds is difference as a productive force, allowing visitors to encounter how artists in both Taiwan and Singapore reworked inherited traditions while staying true to their own creative sensibilities.

Working together and producing new knowledge

For both artcommune and Liang Gallery, this marks the first time that each has collaborated with another gallery to mount a joint show. Such partnerships are rare and require “a lot of trust and friendship,” notes Liang Gallery co-founder Claudia Chen. In contexts where museums began collecting modern Asian art relatively late, private galleries have often functioned as de facto custodians of art history, shaping both scholarship and public memory.

This is particularly true of these specific galleries: Liang Gallery’s mission centres on the research and exhibition of Taiwanese art, while artcommune plays a similar role for Singaporean modern artists. Helmed by an academic curator like Takamori, Mirror Straits demonstrates how private galleries can play a substantive role in art-historical knowledge production and shape how different audiences encounter one another’s artistic histories.

Chen believes that shared cultural roots will help Singapore art appeal to Taiwanese audiences, even as the island’s history as a multicultural port city gives its artistic output a distinctive character. Meanwhile, artcommune founder Ho Sou Ping hopes that the show will encourage audiences both locally and abroad to understand Nanyang art beyond a strictly national framing.

Mirror Straits will travel to Taipei in September. It marks the beginning of a longer-term partnership — and a possible alternative to the costly art fair model for galleries entering new markets. Yet, potential commercial outcomes aside, the exhibition already opens up new ways of thinking about these intertwined art histories. To encounter these eight artists together is to glimpse parallel histories — ones that do not mirror perfectly, but refract just enough to make each side newly visible, even to itself.

___________________________________

Mirror Straits runs at artcommune gallery from 17 January to 15 February 2026, overlapping with Singapore Art Week (22–31 January). The exhibition will travel to Taipei’s Liang Gallery later this year, where it will run from 5 September to 4 October.

Header image: Lee Chung-Chung, Butterfly Fly in the Dream 蝴蝶夢中飛 (2015), ink and colour on paper, 69.9 x 136.2 cm.

This article is produced in paid partnership with artcommune gallery. Thank you for supporting the institutions that support Plural.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

When the Mekong Flows Into a Michigan Museum

Seven Ways to Spend Your Singapore Art Week 2026