One thing I’ve come to believe as a writer is: listen to the call of synchronicity. In October last year, for my first piece for this magazine, I met up with NUS Museum curator Sidd Perez to find out about the Museum’s plans for the upcoming revamp of its Ng Eng Teng gallery.

Walking out of the gallery, I saw another exhibition being put up. The glimpses I saw intrigued me: bold, colourful brush strokes in oil and gouache, playful renditions of birds in Chinese ink. I snapped some photos, registered the unfamiliar name on the wall text, and made a mental note to find out more.

That name was Tan Joo Jong (陈有勇), and a search online yielded little in terms of biography except the bald fact of a life cut short: 1951–1984. There were more images, though, and I feasted on them. A bulging maroon flower (a banana flower?) drawn in a few bold strokes reminiscent of Picasso loomed over a nonplussed cubist bird with spiked hair, who seemed to be asking: what am I doing here? A woman with large, sagging cheeks held in her hand another rough, rudimentary bird. Her beady black eyes were trained on the poor avian. The question this time seemed to be: what exactly are you?

It’s the eyes, I decided, that really make a Tan Joo Jong ( … yes, I’m now an expert, after 5 minutes on image search). His figures seemed to leer sideways, uniting both viewer and object in a space beyond the painting.

A full life cut short

I can’t get these images out of my mind, and so, months later, I turn up to the NUS Museum on a Monday to meet Chang Yueh-Siang, curator of the retrospective Unfettered Brush: The Art and Writings of Tan Joo Jong. Aside from some exhibitions by commercial galleries, the last institutional solo for Tan Joo Jong appears to have been in 1983 at the Goethe Institut, just a year before his untimely death. Unfettered Brush was made possible by a generous loan from the Mong Lee private collection by collector Tan Guee Pang, with assistance from Tan’s widow Mrs. Tan Joo Jong.

Chatting with Chang, reading the exhibition’s catalogue and reports in the newspapers of the time, I put together the life story of this little-known artist.

Born in 1951, Tan Joo Jong did not receive formal art education, aside from the art curriculum at Anglican High School, which he attended from 1964 to 1969. In 1969, he matriculated into Nanyang University (Nantah), where he joined the Nantah Student Art Society, becoming its president from 1973–4. His Nantah years proved formative for his artistic practice: from 1970 to 1972, his sketchbooks were filled with copious sketches of Singapore scenes. He then progressed to executing full-scale works in gouache and oil.

Tan’s diaries reveal his influences, which included Western masters such as Picasso, Matisse, and van Gogh — references evident in his works from this period. He graduated from Nantah in 1975 with a degree in geography, and was then called up for National Service (NS). This marked a turning point in his practice. While he still painted occasionally in oil and gouache, he soon moved decisively into Chinese ink painting as his primary medium.

Amusingly, Tan’s shift to Chinese ink painting was apparently driven by his NS arrangements. Posted to Tengah Air Base, Tan was able to book out every day. Seizing the opportunity, he rented a room near Yunnan Gardens so that he could practise painting daily.

However, circumstances made it difficult to store canvases or use turpentine. Chinese ink proved a more practical and portable medium. Tan then sought out Chinese ink masters, such as Fan Chang Tien and See Hiang To, who aided him in his autodidactic journey. His Chinese ink works span the period 1977 to 1983 and, in the early part of this period, include collaborative works with painters such as Tan Oe Pang, Low Eng, and Fan Chang Tien.

Tan would soon develop his own iconic, idiosyncratic style, described as “courageously breaking away” from conventions of Chinese art by curator and artist Choy Weng Yang. (A commentary published after Tan’s death hinted that there had been criticism of Tan’s bold and rough strokes, which reminded observers of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou — a group of unorthodox Chinese painters from the eighteenth century.) Tan’s idiolect drew reference from the minimalist expressionism of the late Ming painter Bada Shanren, and the primitivism and deliberate clumsiness, as well as the sense of humour, of the modern Chinese painters Ding Yanyong and Guan Liang. Both Ding Yanyong and Guan Liang were noted for their blending of Western and Chinese styles — something Tan would become known for too, with a 1983 Straits Times piece noting how he “melts East and West into a potpourri of cartoon-like originals.”

Aside from his artistic practice, Tan also shaped the development of art writing and discourse in Singapore, with Nantah proving a fertile breeding ground. His senior Ho Kah Leong, who would become a member of Parliament and, later, principal of the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, established the Educational Publications Bureau, which published the landmark publication Singapore Art (新加坡美术). Singapore Art ran to 17 volumes from 1975 to 1981, with Tan serving as editor between 1976 and 1979. He then took up the position of arts editor of the Chinese daily Sin Chew Jit Poh from 1979 to 1983, covering local exhibitions and interviewing eminent artists of the period, such as his idol Guan Liang.

It is from Tan’s writing that one gleans his aspirations for contemporary Chinese ink. In pieces published in the daily paper Nanyang Siang Pau in 1979, Tan declared that Chinese ink painting was “unconstrained by time and space; it is able to harness traditional techniques, and also embody the contemporary spirit of the times.” Driven by this spirit, Tan, along with other luminaries such as Chen Wen Hsi from Singapore and Wucius Wong from Hong Kong, became a founding member of the International Contemporary Ink Painting Movement, an organisation that is still active today.

Tan’s sudden and unexpected death in 1984 brought forth an outpouring of grief from the Chinese literati of the time, a testament to his influence and reputation. A report in Lianhe Wanbao mourned that “a star of the art world has fallen.” In Lianhe Zaobao, scholar and linguist Lim Buan Chay (林万菁), in a piece titled “Crying for Joo Jong (哭有勇),” remembered how Tan would nurture and guide his art students, and how tireless he was in promoting the development of art in Singapore, despite his poor health. Poems were even published in lamentation, with one poem, “Death of an Eagle (鹰之),” comparing Tan to one of his favourite subjects:

鹰展翼飞过

留下寂寞的天空·

the eagle spreads its wings and soars

leaving a lonely sky

While initial reports attributed his death to a sudden heart attack, Shin Min Daily News would report in September 1984 that his death had been ruled a suicide caused by depression, allegedly brought about by his distress at his inability to provide for his family.

Nanyang style reconsidered

Through Tan Joo Jong’s oeuvre, Unfettered Brush presents an opportunity to reconsider “Nanyang style,” a style typically depicting Southeast Asian subject matter while drawing on both Western painting and Chinese ink techniques. While it has been identified with certain key Singapore artists of the 1940s to 60s, Tan Joo Jong’s short but productive career opens up the possibilities of viewing Nanyang style as a longer, more variegated process of Singaporean Chinese artists depicting subjects and objects of the region.

Even in the 70s, artists were still grappling with the concept of a national style. In a commentary published in Sin Chew Jit Poh in May 1979, Tan averred that “if artists lack national consciousness, they will not bring us any sense of belonging, and will not be able to establish a national style or discourse.”

Tan was reported to have visited an artist community in Ubud in June 1983. (This was a markedly different approach compared to the celebrated Nanyang artists of the famous 1952 Bali Trip, who apparently did not make contact with any local artists.) His Balinese scenes are a sharp departure from the expectations established by earlier Nanyang style painters. In a painting of Balinese women, we see that while the woman on the top is presented as a more typical Balinese beauty, ferrying fruit balanced atop her head, the woman on the bottom is instead a rough, angular almost-caricature.

Even his Balinese landscapes seem to refuse expectations: they cannot be easily read as Balinese scenes, and make no concessions to preconceived images of the island.

One is tantalised by the prospect of how a longer-lived Tan Joo Jong might have painted within and against the Nanyang style.

Excavations

Tan’s art writing, amply scattered throughout the exhibition and excerpted in the catalogue, forms part of an underappreciated vein of intellectual life in Singapore — that of the Chinese literati and artists of the 60s to 80s. Bodies like Nantah and the Nantah Student Art Society provided a fertile environment for artistic discourse. Apart from Tan Joo Jong, the school produced other eminent artists and art writers like Tan Swie Hian, Ho Ho Ying, and Ho Kah Leong. Publications such as Chao Foon (蕉风) and Singapore Art further contributed to the rich artistic and intellectual life of the period. Critical debates emerged about artistic style and adaptations of the West, with some artists condemning the indulgent and decadent “formalism” of modern artists like Picasso and Matisse, and others like Tan sharply disagreeing.

Discussions about art even permeated the Chinese newspapers of the day: for example, Sin Chew Weekly carried transcripts from a discussion between interlocutors such as Tan Joo Jong, Liu Kang, Ho Ho Ying, and Tan Oe Pang from a forum in 1981. (They discussed future trends in Singapore painting, as well as the right attitude and approach to take when making art.) With the closure of Nantah in 1980, and a general neglect of Chinese intellectual history in Singapore, much of this history has unfortunately been buried and awaits excavation.

During my visit, Chang told me that she spent years figuring out an angle for the exhibition. Things clicked when she realised that when Nantah was merged with University of Singapore, the NUS Museum also took on the collection of Nantah’s Lee Kong Chian Art Museum. This exhibition was a way to link NUS’s history with Nantah, given the continuity of the two institutional collections, and to showcase how Nantah as a university had been a fertile site for artistic practice and discourse.

Keen to show how Nantah’s intellectual and artistic ferment fed Tan’s life and work, Chang is currently working on a monograph on the artist, titled Boundless Spirit: the Art and Writing of Tan Joo Jong, set to come out in June. It will feature a generous selection of Tan’s art writing translated into English. 2025, the year of the Museum’s 70th anniversary, presents the perfect moment — and site — for a rediscovery.

___________________________________

Unfettered Brush: The Art and Writings of Tan Joo Jong runs at the NUS Museum till December 2025. Find out more at museum.nus.edu.sg.

Header image: Detail of Bali Landscape.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

Resurrecting Our Past Selves: Likenesses at the Goethe-Institut New York

Start Looking at the Floors and Around You: Sights and Sound Bites from Art Outreach’s Art in Transit Tour

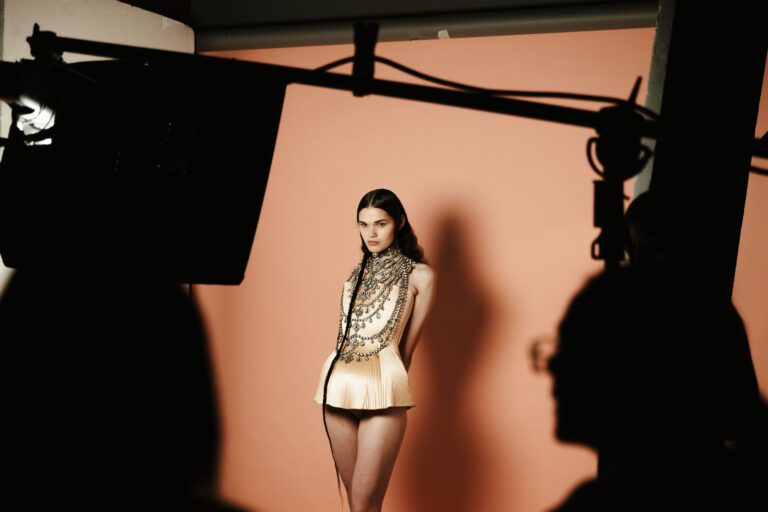

When Couture Gets Crafty: UBS House of Craft x Dior Arrives in Singapore