Singaporeans are no stranger to rapid urbanisation. From the decades-long undertaking that resulted in today’s sparkling Marina Bay Sands, to recent talk of reclaiming a “Long Island” on the east coast and developing rustic Pulau Ubin, the land of Singapore can feel unrecognisable from one generation to the next. This constant shapeshifting makes it easy to lose sight of the past — but not so with local artists Pateo Chang and his daughter Melissa Teo. In weaving a narrative that’s both poignant and artistically masterful, they keep Singapore’s history in conversation with the present.

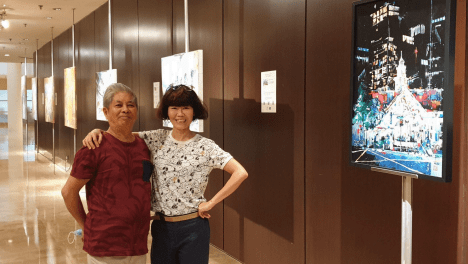

This father-daughter duo first exhibited together in the 2022 show Of Kopi and Kampongs at Utterly Art Gallery on Mosque Street, and then again in These Moments Forever at Pan Pacific Hotel Singapore that same year. But Chang and Teo have been painting together, separately, for much longer than that. Their works form a tapestry of two generations’ worth of local scenes, impressions, and memories.

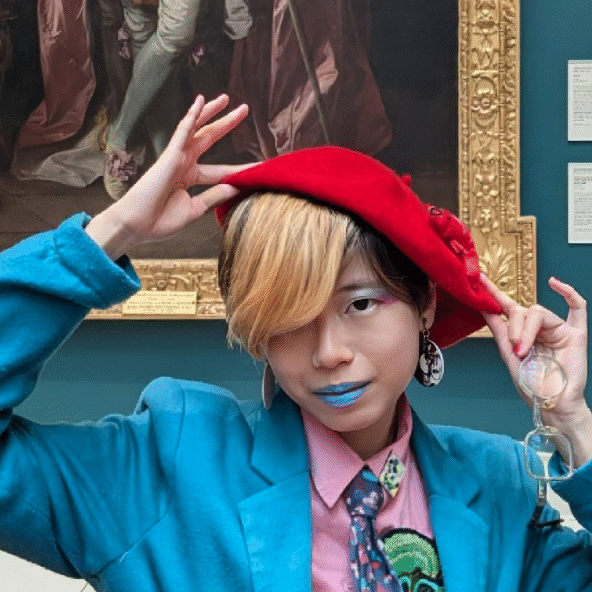

On the surface, achievements such as Chang’s Silver Award in the 2022 UOB Painting of the Year and Teo’s participation in a Live Artists’ Takeover at the 2024 Affordable Art Fair may paint this a heartwarming tale of family and success. Yet, both father and daughter have made it clear that their artistic careers have been no beds of roses. Rather, they have both faced uphill battles in a rarefied industry rife with high hopes and crashing disappointments.

When Teo was a child, Chang repeatedly warned her not to pursue the arts as a full-time career. “It’s not easy,” he says. “It’s a harsh world for any honest creative.” It’s financially unpredictable — an oft-repeated criticism of the arts from the pragmatic Singaporean parent. But when that parent is himself a practising artist, and from a working-class background at that, the criticism rings ever truer.

And for the most part, Teo is right. Their reality is one of cluttered HDB kitchen floors enmeshed with painting space, a far cry from the pristine home studios that one might expect from artist Instagram reels. I ask them why they still keep at it. They don’t know. They only know that their walls are overflowing with canvases, reflecting an irrepressible urge to create in spite of it all.

Chang and Teo prove that there is no need for formal art school training. They attribute their unique styles to their life experiences and having to forge their own artistic paths the hard way. Even between father and daughter, it is apparent that their artworks are only alike in their choice of subject matter and accomplishment. Everything else — their styles, their palettes, their perspectives on their respective Singaporean muses — differs.

Pictures of yesteryear

The Chang I know today is eighty-two, and grasps his paintbrush in hands as gnarled and wizened as his signature sgraffito (scratching) technique. He says he is slowing down, but still his canvases pile up across the cramped living room space and hang from bamboo poles.

But the Pateo Chang his daughter has known all her life has wielded many tools besides the paintbrush in his hands. Change has been the only constant in her father’s life — change and artistic drive, that is. Before becoming a full-time painter, Chang worked as an interior designer and a jeweller, and cites the latter escapade as his first real entry into the fine arts. He even set up his own jewellery business after training at a gemological science institute in the 1980s. But making a living with art is rocky (pun intended), and that venture was eventually dashed in 1999.

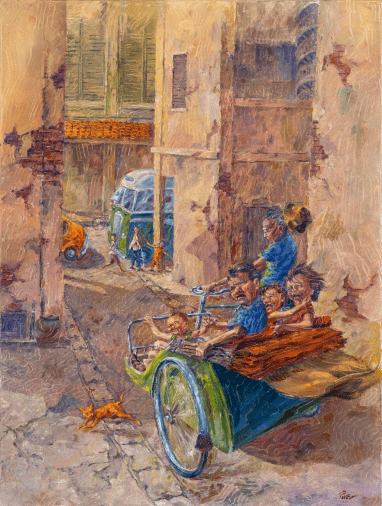

Still, Chang is not one to lose hope in the face of setbacks. In 2004 he revisited his childhood passion of painting, channeling a grim childhood spanning the Japanese occupation and struggle of Singapore’s independence years onto canvas. Most of his works feature earthy kampong or village scenes, toiling samsui women, labourers, and other everyday snippets of yesteryear.

Chang’s canvases are imposing. He builds on layers of paint in the manner of Singapore’s pioneer artists, but uses acrylic instead of oil. And this is no basic re-creation — rather, Chang’s paintings re-contextualise the past. While the pioneer artists depicted their immediate settings, Pateo captures memories that are ephemeral and everlasting all at once.

This is further emphasised by Chang’s signature style. His figures are ghostly, fluid, and sometimes twisted, an effect amplified by the scratchy sgraffito that cuts through his paintings in fine waves and distorts the images as if through a mist of memory. And the faces are highly stylised, sporting big, dramatic expressions — his way of introducing a layer of humour to otherwise solemn subject matter.

After all, these scenes depict bleak, impoverished decades of hardship. “Life was very difficult back then,” Chang explains. It sounds like an understatement, but he says it so casually, his enthusiastic demeanour hardly wavering. It makes sense to me, then, that the caricature-like visages he paints feature exaggerated flashes of teeth and strained creases of the eyes. Their expressions could pass for contorted grimaces but also laughter: a cheery grit that persists despite tribulation.

With their smoky palettes and theatrical lighting, Chang’s paintings are bathed in the romance of nostalgia, placing them within the realm of memory and reflection rather than objective historical record.

Preserving for the future

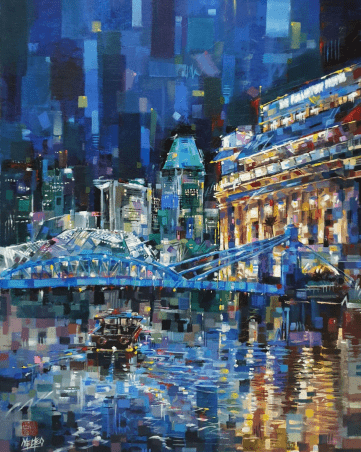

By contrast, Teo approaches her subject matter more from the point of advocacy than nostalgia. She feels that cultural preservation in the face of modernisation is a critical concern for this rapidly changing city. In 2016, her first solo exhibition As If We Never Said Goodbye at Utterly Art featured collages of primarily monochromatic scenes of old Singapore. Like overlapping memories, shophouses, antique tiles, old signboards, and trishaws blurred in an inky aesthetic reminiscent of traditional Chinese painting.

Though she still works with immortalising impressions of street scenes, Teo’s canvases have since become more colourful. Today, her works are characterised by sweeping, spontaneous brushstrokes, and a graphic, patchwork-like application of vibrant colours. The past no longer fades out of view, but demands to be seen in a striking new light. They remind the viewer that many of these old spaces are still brimming with life.

Teo’s call for preservation extends beyond her signature urban paintings to local wildlife and their habitats. This is best exemplified by her second solo exhibition at Utterly Art in 2018 entitled Welcome to the Jungle, but it expands into her other works as well. Old buildings and neighbourhoods bring back fond memories for many Singaporeans, but it is our flora and fauna — which may be less familiar to many in our urbanised landscape — that fall out of sight and mind. “People always forget about wildlife — they hear ‘City in a Garden’ and think that our nature is doing alright,” Melissa remarks. “It’s not just old buildings and places you grow up in and know that are sacrificed. Just because you don’t see [this wildlife] doesn’t mean it’s not suffering.”

From mundane mynahs to elusive creatures such as the critically endangered Raffles’ banded langur, Melissa paints animals in a variety of media. Her trademark style persists through it all, however, with the bold brushwork which imbued so much vigour to her buildings now taking on a tint of vulnerability when applied to living critters. There’s a sense of fleetingness and unpredictability in the way that these creatures’ fates lie in human hands — all their exuberance, once extinguished, cannot be brought back.

There is no sparkling Singapore in Pateo’s and Melissa’s repertoires. Instead, one finds gritty memories and bold calls for a better present, wrapped in expressive brushstrokes. To gaze upon their works is to perceive a wake-up call from two generations who have seen a city that is more than its highs of pristine modernisation and luxury.

___________________________________

Follow Melissa Teo on Instagram at @art_teomel.

Header image: Detail of Melissa Teo’s CADENCE on the Singapore River. Image courtesy of the artist.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

In Retrospect With Sonny Liew — The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye: The Exhibition

Lucy Davis on Art, Ecology, and Inter-Species Connections