Start Looking at the Floors and Around You: Sights and Sound Bites from Art Outreach’s Art in Transit Tour

There are many things that might preoccupy you on your daily scramble for the train: what to eat for lunch, work deadlines, that one sneaky auntie who tries to cut your queue. Amidst these moments, traces of ink that span walls, mosaics that climb columns, and engravings that sprawl station floors often fade into the background. Yet what’s precious about the periphery is how it quietly shapes our sense of place.

Launched in 1997, the Land Transport Authority’s (LTA) Art in Transit programme has embedded artworks across 112 train stations and five rail lines. Artists were selected through an open call, with submissions reviewed by curators and the LTA’s Art Review Panel (ARP).

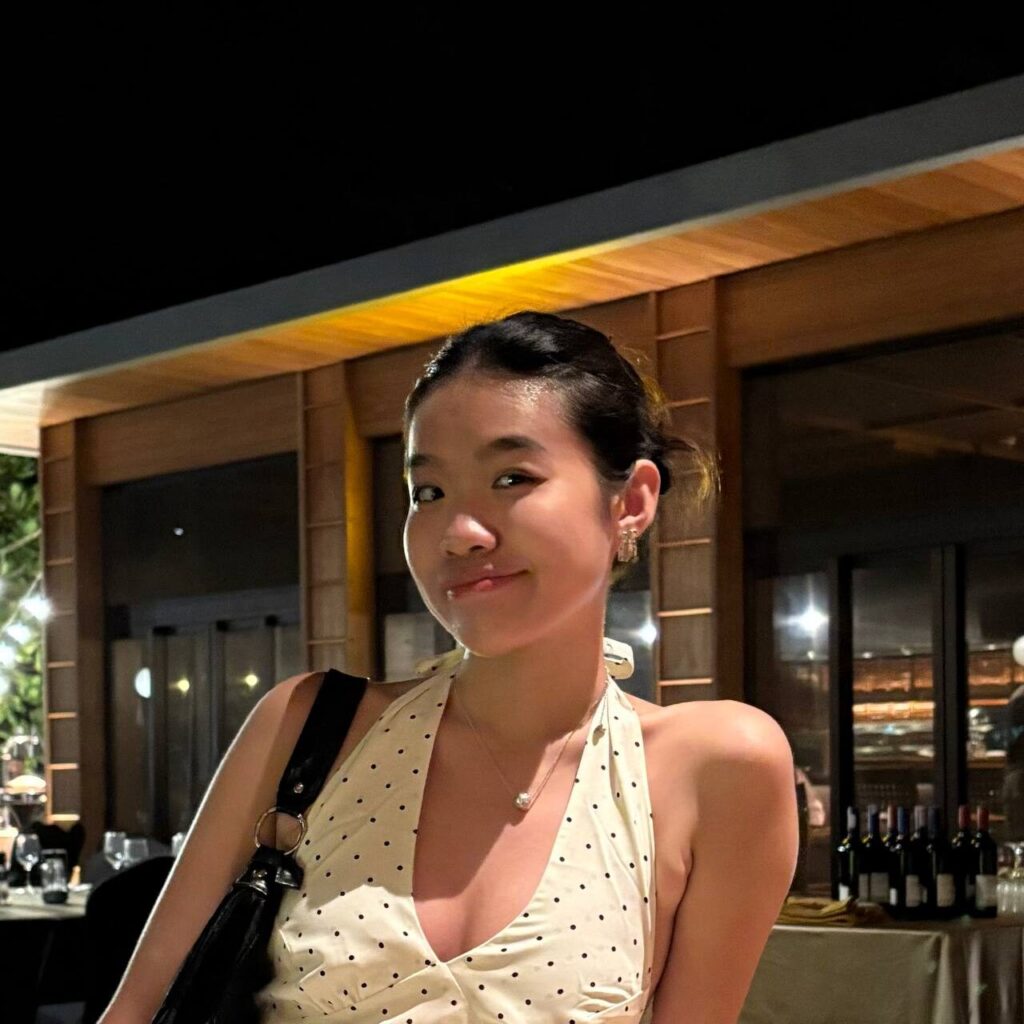

Mae Anderson, chairman of arts non-profit Art Outreach, has served on the ARP since 2012. A long-time advocate of Art in Transit, she has been leading public tours since 2008 to share her enthusiasm for and insight into these artworks.

Here is our little album of sights and sound bites from one of her tours, to inspire your own moments of discovery during your daily commute. She begins with a simple but powerful invitation: “start looking at the floors and around you.”

Art as a means of orientation

From Sun Yu Li’s fish motifs that swim towards escalators at Dhoby Ghaut station to Chua Ek Kay’s tongkang boat “eyes” embedded in the granite floors at Clarke Quay, each stop invites us to look — up, down, and around.

Sun’s Universal Language comprises over 180 installations, from glass plates on columns to vibrant wall mosaics and inscriptions on floor tiles. Drawing on patterns and symbols from ancient cave drawings, the artist uses these as a universal visual code to guide commuters through the station.

Then there’s Chua Ek Kay’s The Reflections at Clarke Quay station. Floor installations form a crucial part of this 3-part work — Chua incorporates pairs of “eyes” from tongkang bumboats into the granite floors. These eyes that historically guided fishermen through Singapore’s waters now direct commuters to gantries and lifts.

At Outram Park station, Wang Lu Sheng’s Memories honours two historical modes of communication that relied on visual cues. In Chinese opera, mask patterns and colours helped largely illiterate audiences to identify character types. Similarly, nurses at Singapore General Hospital once directed patients by telling them to “follow the green line” or “follow the blue line” to reach doctors’ offices. Wang translates these visual codes into stretched lines of blue, green, and black that continue to orient commuters today.

As Memories flashes by like a train in motion, Anderson reminds us, “The[se works] make even more sense when viewed on the go.”

Art activated by motion

Heading up the escalator at Clarke Quay station feels like a slow unfolding of the past through Chua Ek Kay’s 60-metre-long mural, also from The Reflections.

Rendered from ink paintings silkscreened onto enamel panels, the work captures scenes from the Singapore River’s past. Panel by panel, life along the river — once the city’s lifeblood — unfurls before our eyes. The mural ends on an unfinished panel, a reminder that the Singaporean story continues with each journey forward, literally and figuratively.

Nearby, a second installation of 60 brass plates glimmers near the ticketing area, their swirling brown and ochre surfaces evoking the ripples and rhythms of the Singapore River. An ever-changing, abstract masterpiece that invites commuters to contemplate the river as a metaphor for life, The Reflections is a timeless piece that speaks to the past, present, and future.

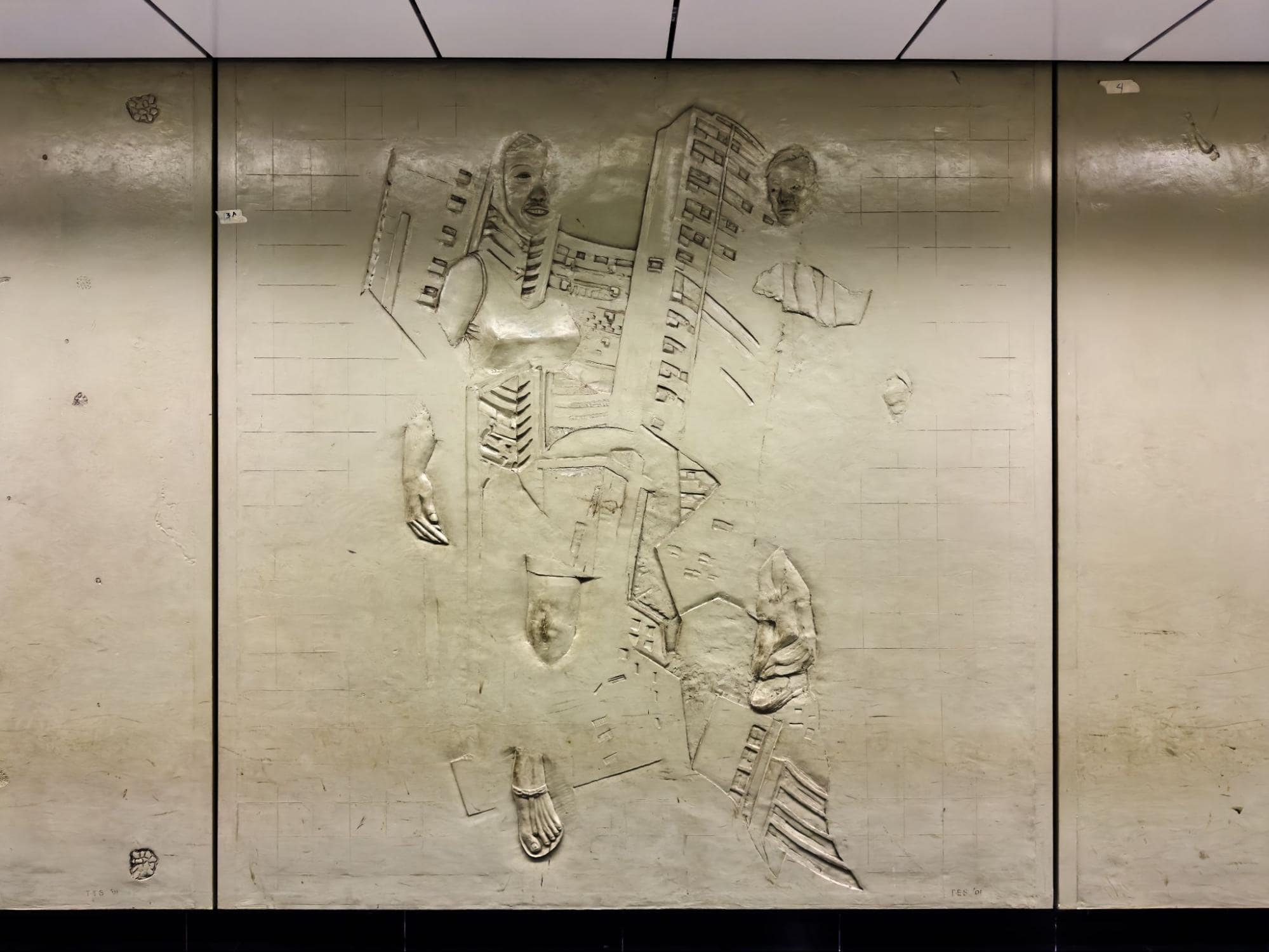

At the linkway at Outram Park, Teo Eng Seng’s The Commuters similarly uses a play of light and shadow to make its concrete relief figures come alive. It draws to mind the way our attention ebbs and flows when we autopilot through our daily commutes.

Meanwhile, at Promenade station, PHUNK’s Dreams in Social Cosmic Odyssey glimmers overhead. Reflective droplets capture light and mirror movement, creating a kaleidoscope that dances with the rhythm of the crowd.

Art as shared memory and identity

Many Art in Transit works pay homage to local heritage, but what intrigued me was the artists’ diverse takes on Singaporean identity. Anderson shared that the open call process celebrates this diversity and does not require works to have visual or thematic similarities to cohabit the same station. As such, lesser-known stories and celebrated heritage can share the spotlight.

At Outram Park station, Hafiz Osman’s Mata-mata draws from photographs contributed by residents. Rendered as detailed line drawings of everyday objects, from hanging ducks to public payphones, these images root the station in its community.

The Downtown Line features equally distinctive voices. At Rochor station, students from the LASALLE College of the Arts created Tracing Memories, arranging drawings of vintage Singaporean objects in the form of a motherboard — a playful nod to the tension between nostalgia and technology.

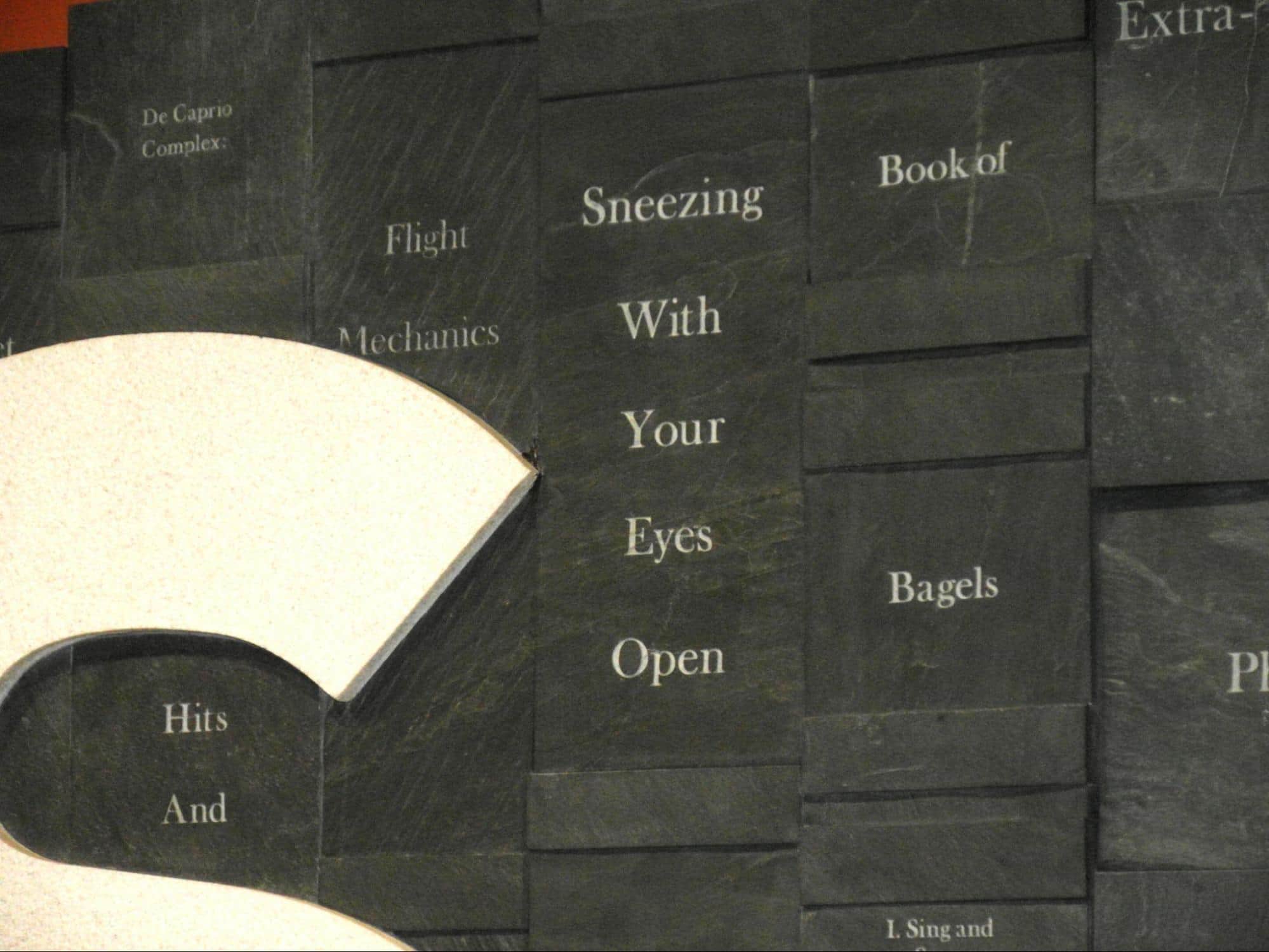

At Stevens, commuters will find a perspective rooted in childlike curiosities and innocence, with Shubigi Rao collaborating with students from the nearby Raffles Girls’ School to generate a booklist of witty titles that they wish were taught in school.

When art and architecture hold hands

Since the programme’s inception, Anderson shares, Art in Transit has championed integration: artworks made to be part of the station’s architecture rather than ornamental afterthoughts.

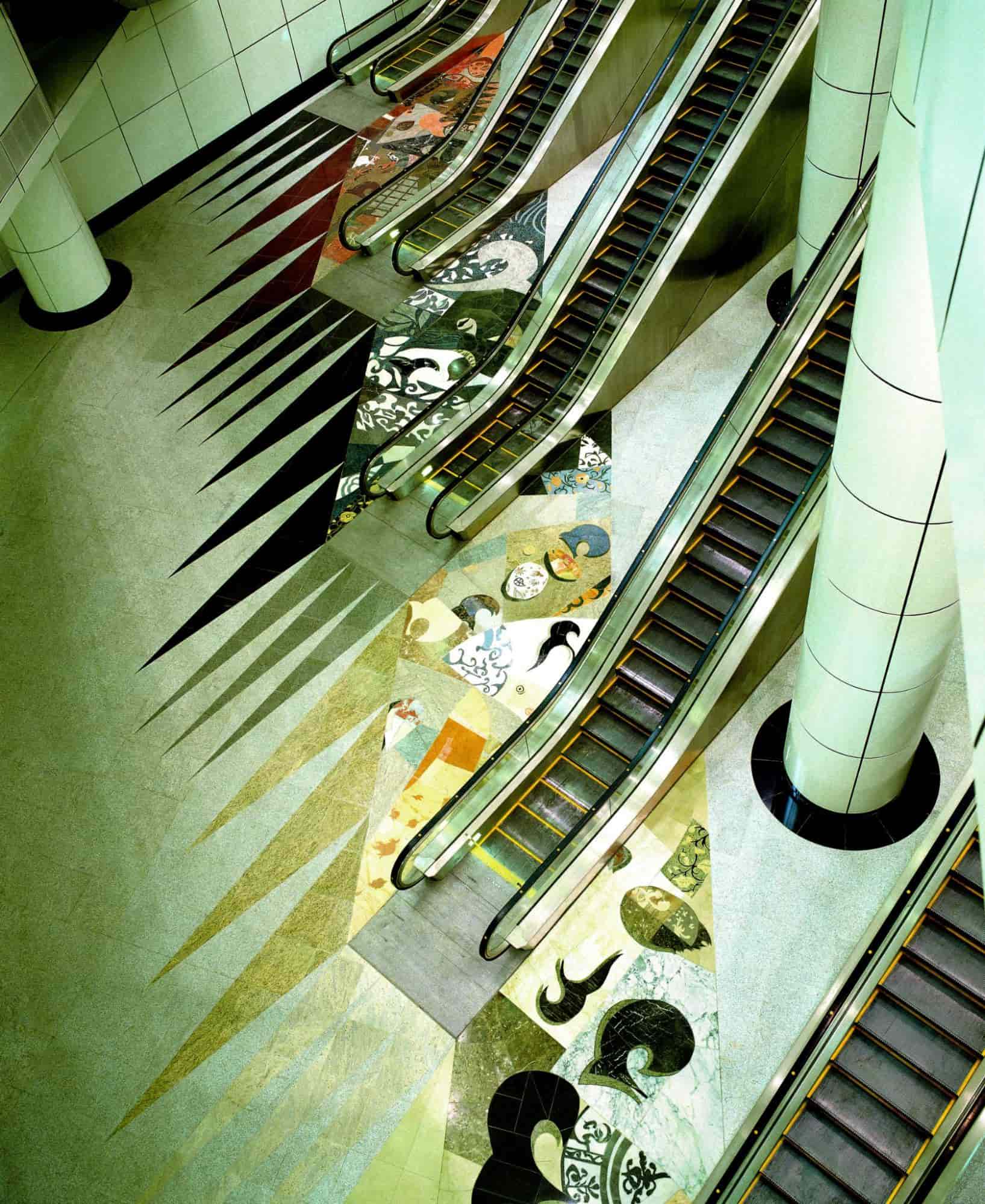

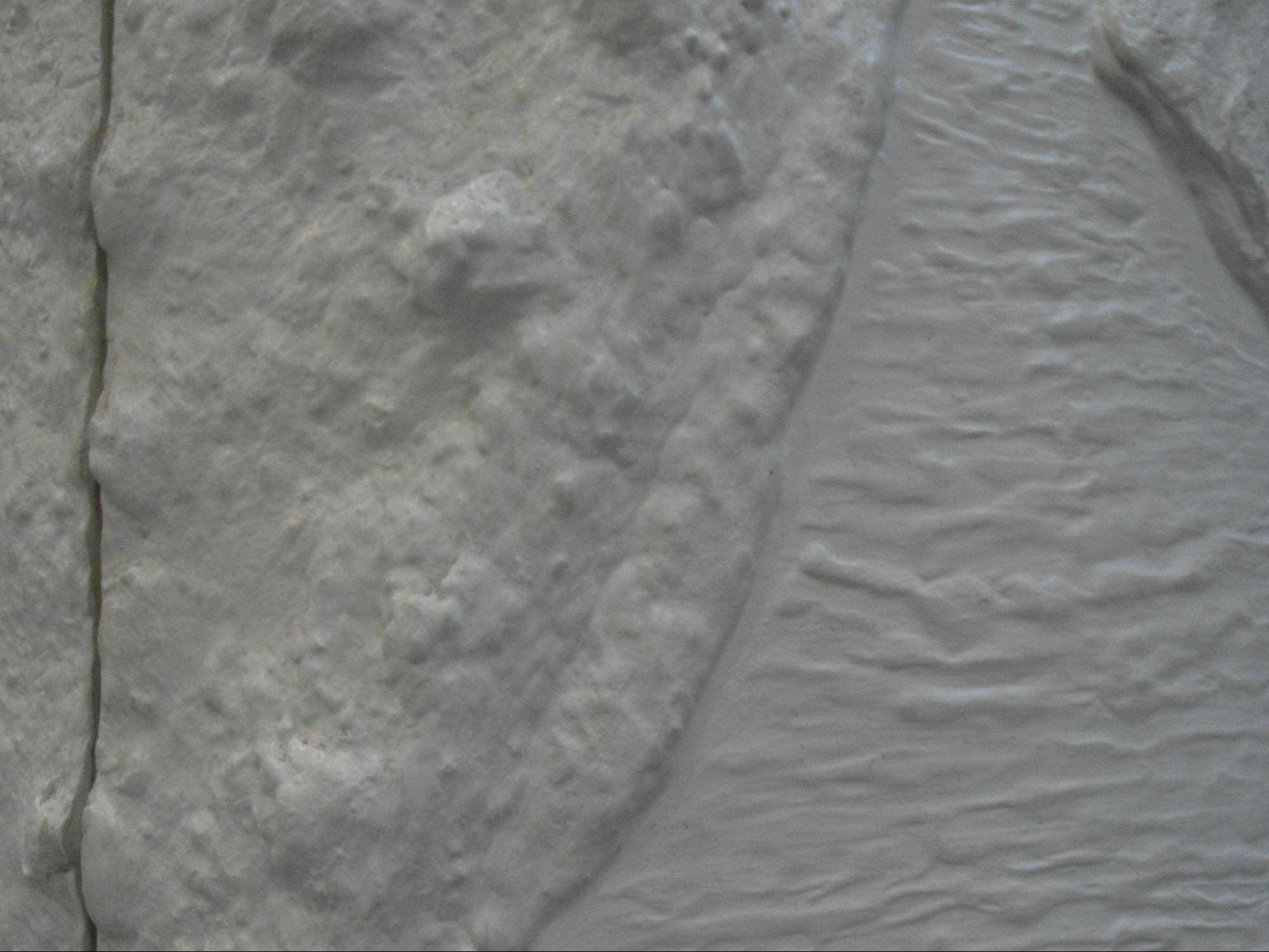

This philosophy shines through in Delia and Milenko Prvacki’s Interchange at Dhoby Ghaut station, where mosaics and ceramic forms wrap around pillars and escalators in rhythmic motion.

Tiles and ceramics are embedded directly into the walls, merging the painstakingly hand-fired pieces of art with the building. Drawing on Chinese, Peranakan, and Indonesian motifs as well as their Western art training, the Prvackis weave cultural exchange into the very bones of the station. Their collaborative process — each fragment and tile meticulously laid with the help of Milenko’s students at the nearby LASALLE College of the Arts — further cements the intimacy of the relationship between the space and its inhabitants.

A similar spirit of integration underpins Twardzik Ching Chor Leng’s PULSE at Orchard Boulevard station. Intersecting pipes and lines evoke both the human body’s circulatory system and the transport network’s connective tissue, producing a meditation on the unseen systems that sustain movement through the city.

Art that invites touch

Having grown up on the museum commandment of “look but don’t touch,” I find that Anderson’s remark about these public works feels radical: “The dirtier it gets with time, the better.”

Under thousands of daily footsteps and grubby hands, dust and dirt settle into grooves of carved stone and metal, revealing textures once invisible. Works like Sun Yu Li’s sand-blasted inscriptions, Teo Eng Seng’s relief sculptures, and Baet Yeok Kuan’s textured columns embrace the accumulation of grime as part of their evolution.

For Man and Environment, Baet enlarged textures of leaves and metal scraps collected from the Dhoby Ghaut neighbourhood, inviting passersby to run their hands across the work’s surfaces. In doing so, the commuters contribute to the slow transformation of its patina.

As Anderson notes, “these works have to work really hard.” And indeed, they do. Even as we rush past, these artworks accompany us as compasses and canvases — quietly mapping space, history, and time. In their silent diligence, they remind us to pause, to notice, and to find wonder in the flow of our everyday journeys.

If you’d like to take a closer look, join an Art in Transit tour by Art Outreach, which journeys through the Dhoby Ghaut, Clarke Quay, Outram Park, Orchard Boulevard, Stevens, Rochor, and Promenade stations. Keep a lookout for their tours on their website and social media!

Until then, remember to start looking at the floors and around you — you never know what treasures you might find.

___________________________________

Follow Art Outreach on Instagram @artoutreachsingapore and visit artoutreachsingapore.org to learn more.

Header image: Delia and Milenko Prvacki, Interchange (2003).

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

When the Mekong Flows Into a Michigan Museum

Seven Ways to Spend Your Singapore Art Week 2026