Crafted from bamboo, fire, and the collective labour of her community, Burmese artist Eindri Kyaw Sein’s towering installation The ember dares to grow. transforms instruments of conflict into a pagoda of hope, revealing the enduring spirit of contemporary Myanmar.

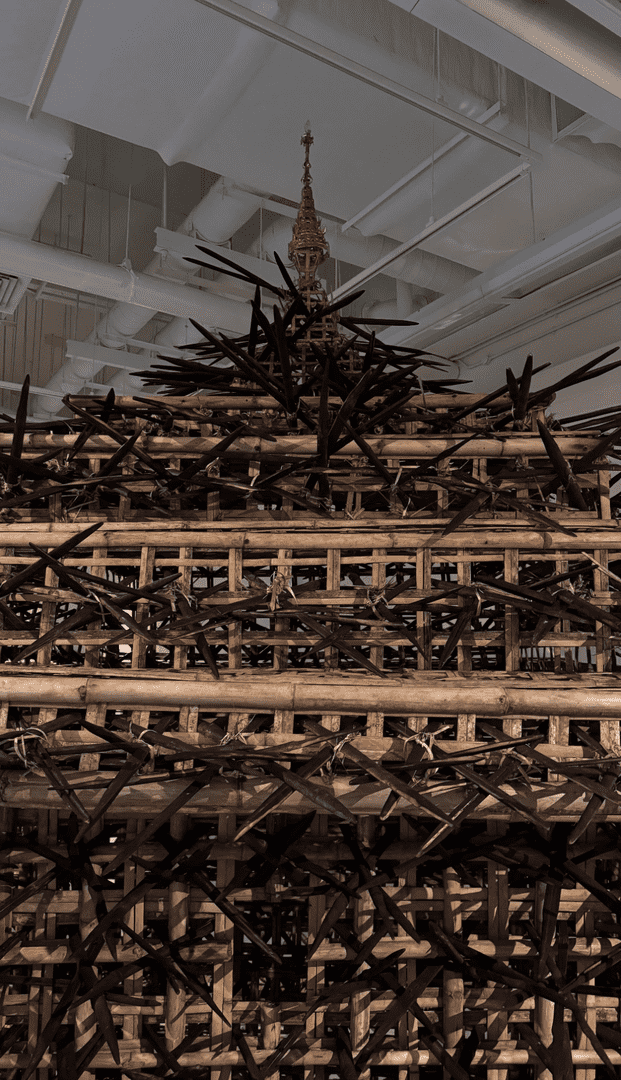

At over two metres tall and three metres in width and depth, The ember dares to grow. immediately commands attention. The work evokes both shelter and threat as it stands in the white-cube space of the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore Gallery, in the LASALLE College of the Arts’ McNally Campus.

At first glance, the bamboo structure resembles a traditional pagoda, an iconic form in Myanmar’s spiritual landscape. Step closer, though, and the blackened spikes jutting from the pagoda tell another story. Reminiscent of the barricades used by Myanmar’s military junta, they speak of conflict, and a nation fighting for its future. This tension lies at the heart of Eindri’s monument to her nation.

Symbols of resistance and resilience

Two contrasting elements anchor the work. Both are made from bamboo, but while the panels form a shrine-like sanctuary, the torched bamboo spikes emerge threateningly from the walls of the structure.

Eindri chose bamboo for its deep cultural resonance in Myanmar, where it is abundantly used and often associated with resilience. The pagoda-like structure relies on traditional techniques — woven bamboo panels and hand-tied joints — that reflect everyday craftsmanship.

The spikes reference the junta’s deadly fortifications, which are typically hand-sharpened with machetes and blackened with a mould-resistant powder for concealment. By charring the wood, Eindri alludes to these barricades and to fire’s destructive role in erasing place and cultural memory.

Through the installation Eindri seeks to explore “the tension of contrasts, emotionally and symbolically: strength and vulnerability, fear and resilience.” As she puts it, the exterior suggests “intimidation, power, strength, and in the interior, a safe and vulnerable place.” These dualities mirror the lived reality of the Burmese people today.

A collaborative monument to heritage, community, and craft

The concept for the installation came to Eindri during a road trip through northern Myanmar with her father in early 2025, when she was a Fine Arts diploma student at LASALLE. She began shaping the concept through conducting research into Mandalay’s architectural heritage, sourcing bamboo, and coordinating construction with her community. Understanding Eindri’s work begins with understanding the role of place, tradition, and the unseen collaborators behind it.

Conceived and built in Mandalay — Myanmar’s former royal capital and its enduring cultural and religious heart — the installation is rooted in a city where craft traditions and monastic communities persist despite a long history of conflict and political upheaval.

Using her father’s construction site in Mandalay, Eindri supervised the build and worked alongside local craftspeople. She learned the weaving and tying techniques for the bamboo panels from streetside weavers and construction workers whom she sought out, who still use these methods in their daily labour.

The stupa crowning the installation was crafted by artisans in Bagan, the UNESCO World Heritage site renowned for its thousands of temples and pagodas. The monuments of Old Bagan were key reference points as Eindri worked to preserve authenticity. Aware that contemporary reinterpretations of religious forms can be sensitive in Myanmar, she also sought guidance from a historian and architect involved in restoring Mandalay Palace, ensuring the work remained respectful and representative of its rich tradition.

Pagodas are symbols of memory and heritage, and they embody the spirit and identity of Myanmar. “For me, they aren’t just sacred sites,” Eindri says. “They are places of freedom, exploration, beauty, and connection, a dreamlike escape where I could engage with Myanmar’s cultural soul and its people.”

Eindri says that it is important to understand how deeply religion shapes the spirit and identity of Myanmar. “It’s more than ritual or belief; it’s a source of inner strength, resilience, and social connection,” she notes. “In Myanmar, temples and pagodas are not only sacred spaces, but also places where people gather, share, and find a sense of belonging.”

Her work reflects Myanmar’s fraught dualities, where temples become makeshift sanctuaries in times of crisis, symbols of peace existing alongside spiky barricades. “In moments of unrest, survival and spirituality mix,” she muses. “I hope to reflect a deeper truth: that even in instability, there remains a profound and enduring connection to faith and community.”

Working under watchful eyes

Observing the junta barricades required caution. The visual references Eindri used were based on photographs taken discreetly, from a moving vehicle, during road trips from her home in Yangon to Mandalay. She was careful not to draw the attention of the soldiers stationed near the barricades. Despite the risks, she made detours in order to more closely observe the barricades, and arranged for close-up photographs to be taken. The resulting reconstruction came together after many rounds of experimentation, and from the varied input of local construction workers and engineers.

Transporting the materials out of Myanmar posed its own set of challenges. Concerns arose regarding how the sharp spikes could be construed as weapons. Although Eindri blunted the spikes prior to transporting them across military checkpoints, armed officers halted her and her father at the final checkpoint. She explained the project as an attempt to spotlight Burmese craft on an international stage. “To my surprise, the soldiers were supportive,” she says. “It reminded me that beneath the politics and war, we are still people who believe in a better future.”

Rebuilding the work in Singapore came with its own challenges. The installation had to be designed in the form of modular, labelled components that could be dismantled in Mandalay and reassembled at LASALLE. Transporting the bags of blunted bamboo sticks required official clearance from Myanmar’s authorities, and the school’s lecturers and mentors stepped in to help Eindri navigate the bureaucracy and export logistics.

Once in Singapore, Eindri rebuilt the structure with the help of a lecturer and volunteers, some of whom were from the local Burmese community. They resharpened and finished the spikes before assembling the work for exhibition. The process underscored the collective effort behind the piece and the determination required to bring a work shaped in Myanmar’s fraught landscape into an international context.

Now that Eindri is back in Myanmar, she faces an uncertain future as an emerging contemporary artist. But despite the heaviness that the ongoing civil conflict brings to daily life, she remains optimistic about the role art can play in imagining possible futures and shaping perceptions of her homeland. It serves only to “deepen my desire and determination to share my perspective with the world,” she says, reflecting the boldness in the very title of her work: The ember dares to grow.

___________________________________

The ember dares to grow. by Eindri Kyaw Sein was exhibited in the May 2025 showcase of work by graduating students of the LASALLE Diploma in Fine Arts programme, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore Gallery at LASALLE’s McNally Campus.

Header image: The presence of the installation work, The ember dares to grow., comprising woven bamboo panels and torched spikes arranged in X formations, fills the gallery space. Image courtesy of the artist.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

Coconut Kinships: Rethinking Boundaries with Isa Pengskul’s Becoming coconut

Ghostwriter: Communicating with Jo Ho’s a developing slate

Preserving Barbershops of Yesteryear: Barber by Ng Siang Hoi