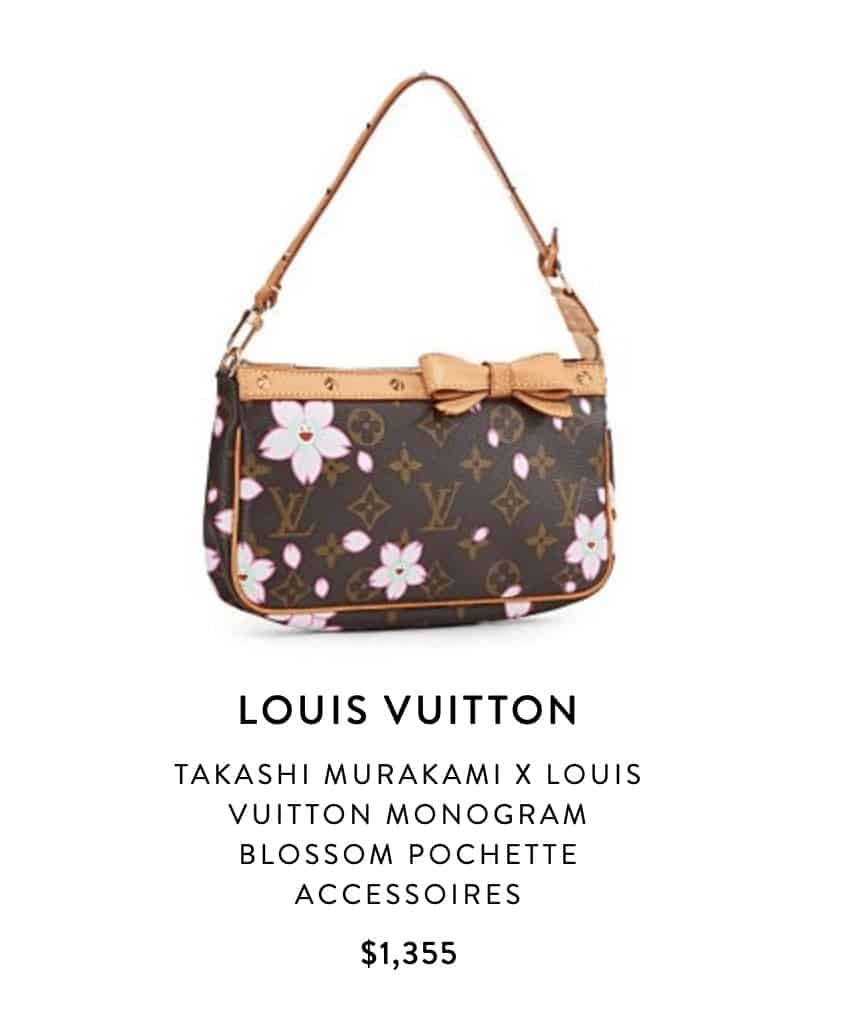

I remember when the first handbags of the Takashi Murakami x Louis Vuitton (LV) collaboration were released to the public in the early noughties. I knew very little about art back then, but something called out to me when I saw those bags. LV was a brand hitherto gloriously unknown to me as a young trainee lawyer and civil servant, an ignorance which was borne out of the sheer unattainability of the product. I mean, what did it matter if I didn’t know the difference between a Speedy and a Neverfull when the fact was, I could Neverafford either of them?

And yet, looking at those Murakami handbags for the first time, a new awakening sparked in the consumerist depths of my soul. The heavy brown leather was now dotted with bright and colourful flowers! Bug-eyed cartoony characters propped themselves up against LV’s iconic stamped logos!

Suddenly, I wanted to be the kind of girl who carried an LV x Takashi Murakami handbag.

The bag was the embodiment of many contradictions – it was approachable with its punky anime energy, but still expensive enough to communicate that its holder was a person of means–someone who had worked hard to afford the heft of its pricey leather, someone who should be taken seriously, someone who understood the intersections between art and fashion and who could have delicious words like ‘artist’ and ‘limited edition’ roll off her tongue.

That bag would speak for me without my having to say a single word. Sadly, on a junior civil servant’s budget, LV-style unorthodoxy remained well beyond my means that year, and for many years after. I would in time to come, learn to feel shame when friends and colleagues talked about buying home furnishings for a fraction of the price of the luxury goods that I coveted.

The dollars and cents on price tags took on a new meaning over time. If measured in things like the late hours spent at the office, or the fear, stress and sleepless nights endured before important meetings, then the cost of a designer bag seemed even more impossible to bear than ever before. A few years after that, once I’d worked in the non-profit sector, the prices of designer products seemed even more repugnant–vulgar even–in the face of the crippling poverty and problems faced by a segment of my fellow Singaporeans.

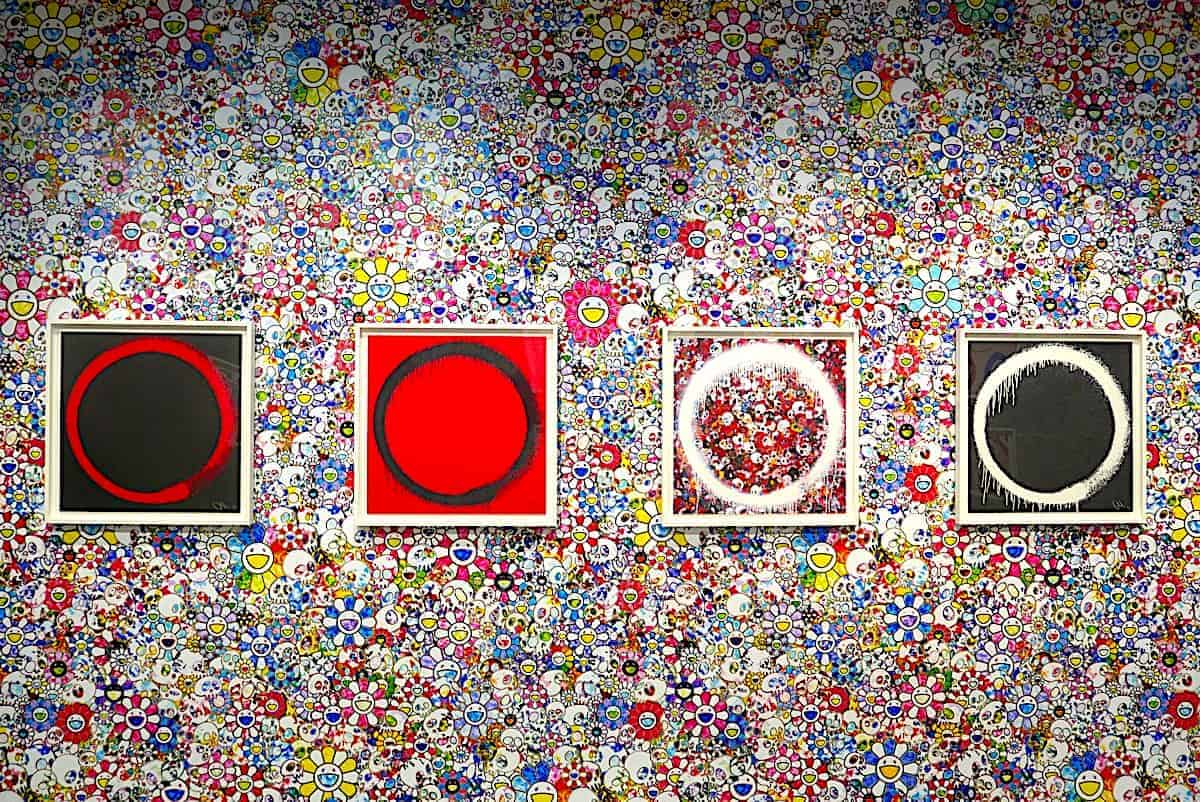

And now here we are, in 2019, where I find myself at the press preview of Takashi Murakami’s first Southeast Asian solo exhibition From Superflat to Bubblewrap.

Held at STPI Creative Workshop and Gallery, the show is set to be a knockout, yet another star in Singapore’s firmament of blockbuster exhibitions. An artist talk on 13 July sold out within 33 hours of it being announced, and hundreds of people are reportedly expected at the show’s official opening on 12 July.

The exhibition sees some new print work, but it is the paintings produced this year (and inspired by the practice of Michel Majerus) which provide the show with its shock-and-awe factor:

From Superflat to Bubblewrap looks back at Murakami’s famous Superflat movement, his homage to the two-dimensionality that can be found in art forms as different from one another as ancient Japanese scroll painting, and manga. At the same time, the exhibition looks forward, with new works showing the influence of street culture in Murakami’s practice. Named ‘Bubblewrap,’ Murakami’s new direction seeks to investigate the 1980s when the Japanese economic bubble was at its height, as well as the post-bubble period.

STPI Gallery Executive Rachel Tan explained that Murakami had a sense that the Japanese wanted “to put the bubble economy away, almost like the way bubble wrap is used to wrap ceramic art when being transported.”

Ceramic she explained, was highly sought after during the economic bubble but when the economy collapsed, this interest waned as people sought out more functional kinds of pottery. Murakami draws inspiration from this sense that the Japanese idea of beauty is closely tied to economic change and in his view “Japan has become a society plagued by deflation…(with) no hopes and dreams to speak of, amidst a prolonged economic recession.”

And what would a Murakami show be without its merchandise? In 2007, the show © Murakami, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, offered yet more special LV handbags for sale. Initial cries of protest questioning the museum’s curatorial vision and the appropriateness of turning the site into a “sort of upscale Macy’s” faded quickly into the background.

Quite apart from Murakami x LV, countless other artists such as Yayoi Kusama, Jeff Koons and even Piet Mondrian have entered into partnerships with fashion brands (see a great list here).

So, how should we think about such approaches to art? The (perhaps) most obvious response is that the commodification of artworks serves to cheapen or contaminate the art, reducing the works to superficial objects for consumption. But then again, what is art at all, if not a good of ostentation that is to be consumed, whether through collectors’ purchases on the art market or through general viewing by a public audience? One might argue that at the very least, a handbag or museum store trinket can be put to practical use, as opposed to an art print hanging uselessly off your walls.

(STPI sources informed us that the works in From Superflat to Bubblewrap range in price from approximately S$2,000 to 4,000 for prints and US$ 400,000 to 2,000,000 for paintings. With these relatively affordable entry prices, the gallery has seen considerable interest from new collectors.)

One good way of understanding the whiff of rampant consumerism that attaches itself to Murakami’s works lies in the very nature of the works themselves.

Murakami has always talked openly about his economic goals. Gunhild Borggreen in her chapter Art and Consumption in Post-Bubble Japan From Postmodern Irony to Shared Engagement in the book Consuming Life in Post-Bubble Japan explains that Murakami had been inspired by 1960s’ pop-art hero Andy Warhol when he established an art factory in 1996 (first named Hiropon Factory and later refashioned as the multinational company Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd). Like Warhol’s factory, it hires people to produce his artworks under careful guidance, and also to manage all business aspects of art production and sales.

Art critic Scott Rothkopf (quoted in the same book) argues that Murakami “demonstrates more than anyone the way in which art can be co-opted for branding purposes and how the art market succumbs to broader economic systems with regard to investment strategies and sponsorships.”

It is important to remember that Murakami was a member of the ‘new breed’ of artists (also referred to as shinjinrui) who grew up during the 1980s and experienced the growing affluence of middle-class Japan and the rise of mass consumption in the country in that decade, and in the 1990s. Together with artists such as Kenji Yanobe, Murakami offered new perspectives on the relationship between art and consumption. This engagement looks set to continue with the artist’s conceptual exploration of his newly-invented Bubblewrap movement.

His works are cartoonlike, but they are also exaggerated and over-the-top. There is a vulgar quality to the art, epitomised perhaps by its garish busyness and repetitive motifs.

Put another way, Murakami’s work is about Japanese commodity culture and all its warts. It exaggerates, distorts and perhaps, undermines consumerism.

Viewed through this lens, the purchase of some merchandise seems almost like an extension of the artwork itself. You, the viewer can also become part of Murakami’s tongue-in-cheek, ironic views on profligacy and waste. In buying the merchandise, or indeed the work, you too are taking part in a massive performance, joining the artist in making a powerful statement on the philosophies of consumerism. (Or, you could just call BS on all this –dismiss it as airy-fairy esoteric nonsense, a silly kind of justification to make people feel better about wasting their money.)

At STPI, the merchandise available for sale includes Murakami-themed plushies, stationery and tote bags amongst others. No major designer collaborations are planned this time.

When confronted with the possibility that Murakami merch might be available at STPI, something stirred inside me again!

Was it because I could now afford these things? Was I reacting to the comment that the store was likely to sell out on the show’s opening night? Or, was I thinking about my twentysomething self–overworked, overwrought, conflicted and seeking for answers and a sense of identity in all the wrong places (read: designer handbags)?

Perhaps it was all of these things, or perhaps it was none of them. Perhaps I will make a trip back to buy something small if anything is left after opening night. STPI and Murakami might get some money from me, but what I derived from the show was a wistful walk down memory lane, a chance to think critically about the intervening decade-and-a-half from when I was last interested in anything Murakami – related, and the opportunity to articulate and share those thoughts.

And those things dear reader, are simply priceless.

_______________________________________

From Superflat to Bubblewrap opens to the public on 13 July 2019 and runs till 14 September 2019 at STPI Creative Workshop and Gallery