On the opening night of The Buddhist Bug: A Creation Mythology by Cambodian-American artist Anida Yoeu Ali, I brisk-walked to Wei-ling Contemporary. I was running late, but at the back of my mind I thought, “Well, it’ll probably start on Malaysian time.” In other words, late. But when I arrived at the gallery, I was confronted by the artist, already outfitted in her bright orange bug costume, swaying and undulating just inside the gallery entrance. I stood with the other latecomers, afraid to enter the gallery and disturb the performance.

Eventually, one of the assistants at the gallery beckoned us in. So we tiptoed in, ducking our heads apologetically as we tried to get into the gallery as unobtrusively as possible. The Bug made eye contact with each of us. A slight smile on her face.

Slowly, the atmosphere in the gallery became more relaxed as guests began interacting with The Bug. One man got onto his knees, face-to-face with The Bug and mirrored her bowing and swaying movements. A little girl darted about, pretending to take photos. Another child pressed close to her mother, not daring to move closer. Gradually, more people warmed up to the performance and began to participate. Some people got so close to the artist that I wondered how comfortable she was with the proximity of all these strangers – nuzzling her face and intertwining their bodies with hers.

“Children love the Bug. They totally engage. They come up to her. They get freaked out and then they want to play, tease and taunt her, hold her and pet her. Children have the best reaction.”

The unfurled body of The Bug, all 100 meters of it, completely transformed the gallery space – suspended overhead in loops from the ceiling, draping gently to the floor at times and forming arches for gallery visitors to walk through. The installation process, I was later told, had taken three days. Tracing the entire length of The Bug’s bright orange body as it wove its way through the gallery space, I eventually arrived at its other end, where a pair of human legs shifted and moved, somewhat disconcertingly.

The Buddhist Bug is an interdisciplinary project that is part performance-installation, part photography and video documentation. A Muslim Khmer refugee who fled Cambodia with her family as a small child, the artist was raised and grew up in Chicago in the United States, only returning to Cambodia as an adult some 30 years later. The Buddhist Bug project is rooted in an autobiographical exploration of identity – from the artist’s personal struggles with issues of assimilation and belonging as a refugee and an immigrant growing up in America, to her more recent experiences as a Muslim woman in predominantly Buddhist Cambodia.

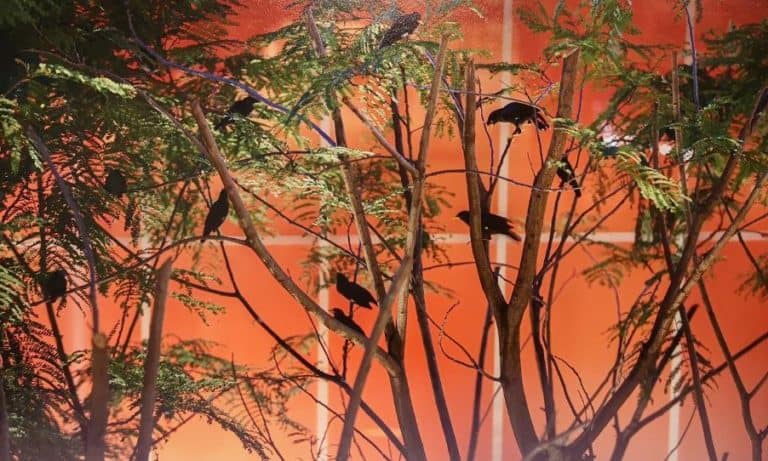

On the gallery walls are photographic artifacts of Yoeu Ali’s site-specific performances where she has purposefully inserted the otherworldly saffron-coloured Bug in classrooms, rice fields, on a cyclo riding through the streets of Phnom Penh and among the people and scenes of everyday life throughout Cambodia. When other people are present in these scenes, their faces often reflect wonder or bafflement or sometimes, a mixture of both. These same reactions were present among the visitors to the gallery on the evening of the opening – our discomfort at her strangeness soon dissolved into amusement as the Bug’s playfulness transformed our initial reactions so that we could stand back and think, isn’t this outlandish and amazing and funny?

This disarmament through humour is a deliberate tactic by Yoeu Ali. Her previous works have been, in her own words, “really politically charged”. However, with The Buddhist Bug, joy and humour add unexpected nuances to a piece that addresses themes of displacement and religious tolerance. “I sort of ended up with pieces where I tried to trick the audience, the viewers, into having this conversation with me. They become complicit in this dialogue that I’m trying to have,” Ali said, when asked about the playfulness of the piece.

As I took a closer look, this dialogue became clearer. Why orange? Why does the head of The Bug look like a tudung or Malay style headscarf? Why is it a Buddhist Bug? Why a bug at all? The genesis of the bug’s form began after Ali’s first child was born in 2008 and she was gifted a child’s play tunnel: “the moment I rolled that out and my child started to interact with it, she sort of crawled through it. I noticed that it could compact and then could easily build out … I just thought to myself … whatever it is that I’m making, it has to incorporate this form.” The Bug can be packed up easily, a characteristic rooted in the project’s exploration of Ali’s displacement from Cambodia as a refugee, “[it is] referencing the ideas of what refugees go through … they take only what they can carry.”

At the same time, The Bug, which both moves and is a vessel for movement, opens up possibilities of perspective. In the photographs of The Bug in Cambodia, the work’s ability to unsettle our simple ideas of natural and unnatural is evident. In Secret Lagoon, the bright artificial orange body curling around the muted browns and earthy greens of coconut trees and a murky river draw our attention to its artificiality. Whereas in Into the Fields, The Bug’s body mirrors the orange sunset and blends into the landscape.

This ability of The Bug to both disrupt a naturalistic scene and at the same time harmonise with its surroundings embodies the duality of Ali’s insider/outsider perspective as a disaporic artist of mixed heritage. Despite the freedom of this perspective, Ali feels that the work is still an expression of her “loss of identity.”

The fact that this exhibition, the most complete showing of The Buddhist Bug to date, is taking place in Malaysia adds another layer to the work. A Malaysian audience is able to pick up the reference of Ali’s Muslim identity in The Bug costume, something not immediately legible to an American audience. The receptiveness and engagement of the crowd on opening night in Kuala Lumpur also fed into the performance. Ali was only supposed to perform for thirty minutes, “time could have passed real slow if it’s not the right audience, but time felt like it was going at a good pace and I felt encouraged to keep going.” It is also meaningful for Ali to see the work travel from the United States, to Cambodia and finally to Malaysia, “it’s allowing me to really trace those migration patterns [of her family].” (In another interview, the artist has explained that most of her father’s side of the family is in Kota Bharu – that he is, in fact, half Malay, half Cham – and her mother has family in KL and Terengganu.)

This extra layer of movement feels especially satisfying to uncover when considering The Bug’s genesis as a tunnel. On the far wall of the gallery is an orange wall with a poem by Ali. One column reads:

orange/tangerine

both a bridge and a tunnel

across and over

Where are we now, at the end of this bridge/tunnel? No concrete answers emerge, but this ambiguity is something Ali now embraces, “I think that that in between-ness, this is something that I have come to terms with as a transnational artist. I think that I now have that ability to own that privilege of being able to work in multiple places and even being accepted as someone who can sort of transcend multiple locations, cultural barriers and identities.” The Buddhist Bug is a perfect reflection of this hybridity, both natural and unnatural, an insider and outsider, a marriage of two faiths in one body. You can’t help but feel like some distance is being bridged.

[Editor’s Note: The Buddhist Bug – A Creation Mythology is on at Wei-Ling Contemporary in Kuala Lumpur till 18 August 2019.]