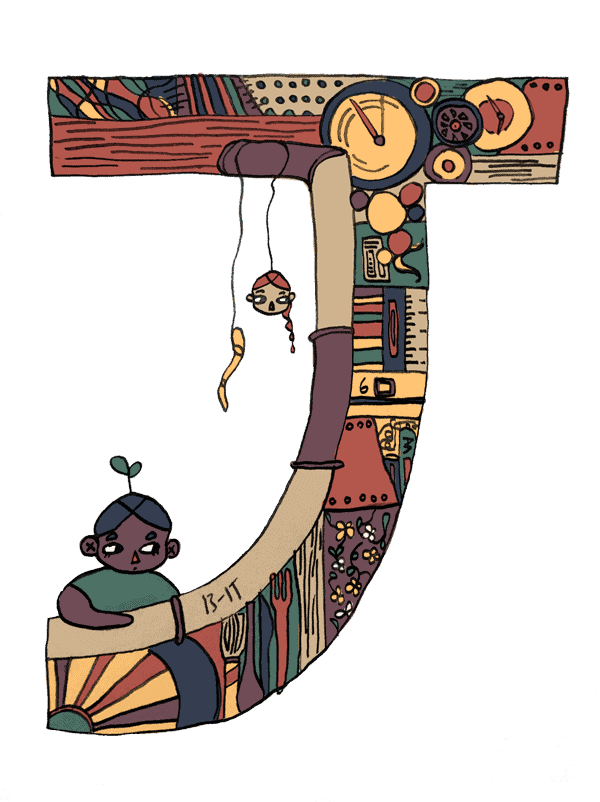

… is for Junk Art.

The saying that “One man’s junk is another man’s treasure” could very well characterise the use of junk in art-making, where discarded items are celebrated as art. Having emerged from its predecessor, found art, junk art finds its roots in the rebellious Dada movement which proclaimed that art can be made out of anything. It is now considered a sub-genre of found art, with its defining mark being the use of banal, ordinary, everyday materials, and quite literally, trash.

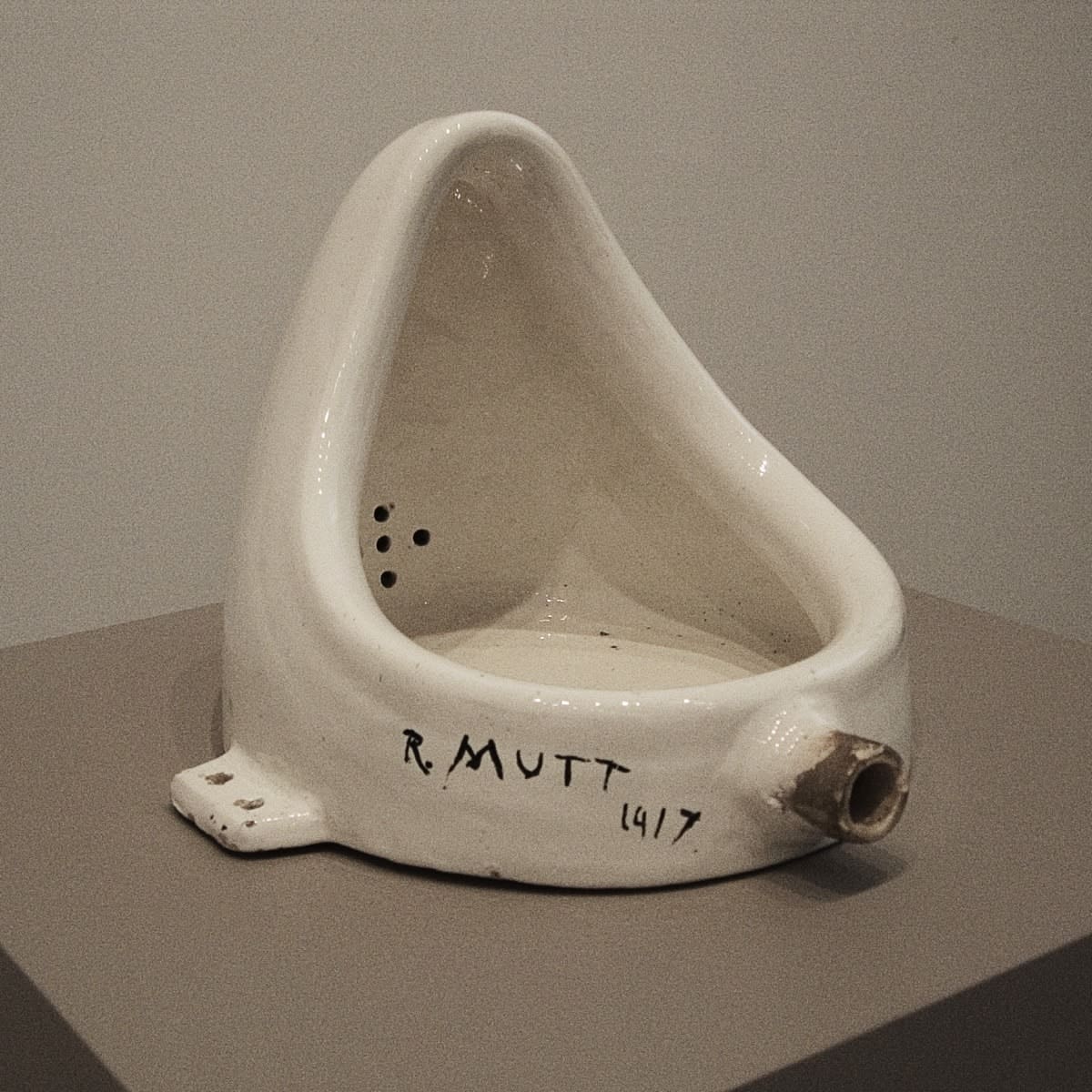

When Marcel Duchamp, a famous exponent of the Dada movement, first called a urinal Fountain, he ushered in the ‘readymade’ – a mass-produced article, randomly chosen, taken out of its usual context and presented as a work of art. This marked the start of what we now know as found art. 20th Century artists who would come to adopt Duchamp’s ideas include Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who produced mixed media collage works during the Synthetic Cubism phase, and Vladimir Tatlin, the “father of Russian Constructivism” known for his sculptures.

The junk art movement branched out of this, being established in the 1950s by Robert Rauschenberg with his experimental works or combines. One of his famous works, Bed, features his own bed, worn-out pillow and sheets dripped with paint in the style of abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock. The term “junk art” was then formalised by British art critic and curator Lawrence Alloway who coined it in 1961, referring to sculptures, paintings, or mixed-media production made from scrap metal, broken-up machinery, objects from rubbish dumps, rags and wastepaper. This approach was perpetuated by French-born American artist, Armand Fernandez, who used debris, gas masks and revolvers in his assemblage pieces, and Marseilles artist, César, who made his sculptures out of car parts. By displaying these waste objects in the realm of art, these key junk creatives gave old, abandoned waste new life.

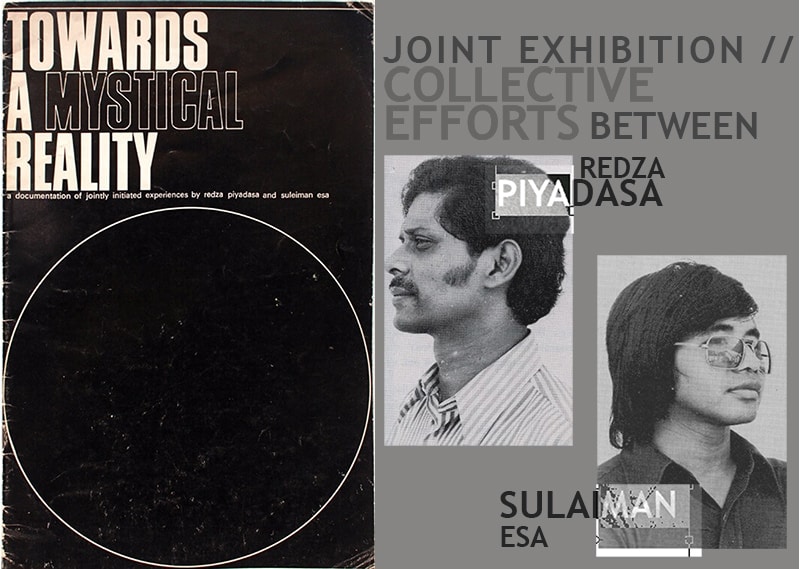

In the 1990s, the art group Young British Artists vested new meaning into junk art, with their use of personal and controversial objects. From Damien Hirst’s A Thousand Years made from a cow’s head, maggots and flies, to Tracey Emin’s My Bed of sweet-stained sheets and stained underwear, these marked a departure from the traditional notion of aesthetics. Since then, artists have been using the abandoned and discarded to create work ranging from the traditional painting and sculpture, to the installation and the conceptual. Among them are Malaysian artists, Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa, and contemporary practitioners such as Victor Paul Brang Tun.

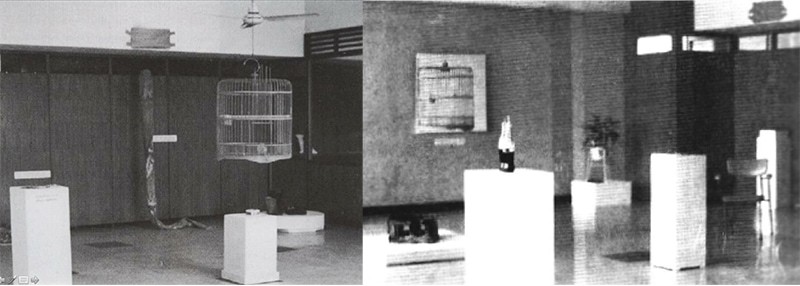

Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa boldly sought to carve new directions in Malaysian art, assigning artistic status to everyday objects by exhibiting them in a gallery space. Their seminal artwork-cum-exhibition, Towards a Mystical Reality: A Documentation of Jointly Initiated Experiences (1974), brought 10 items taken from their original settings into the exhibition, unaltered, ranging from an empty chair, to a potted plant and a discarded raincoat, all of these bearing marks of usage, growth, wear and tear. All of them were products of the environment from which they hailed, bearing stories and stains of their past, which this artist duo advocated as a new, ‘conceptual’ way of understanding reality. These found objects were positioned as ‘events’ located in time and space, rather than simply ‘visual food’ for consumption dislocated from their origins. This movement challenged Western ideas of art where works are deemed as ‘art’ by virtue of artistic manipulation. As Marcel Duchamp’s urinal sought to push the boundaries of art, Piyadasa and Esa’s odd assemblage sought to redefine art in their Malaysian community.

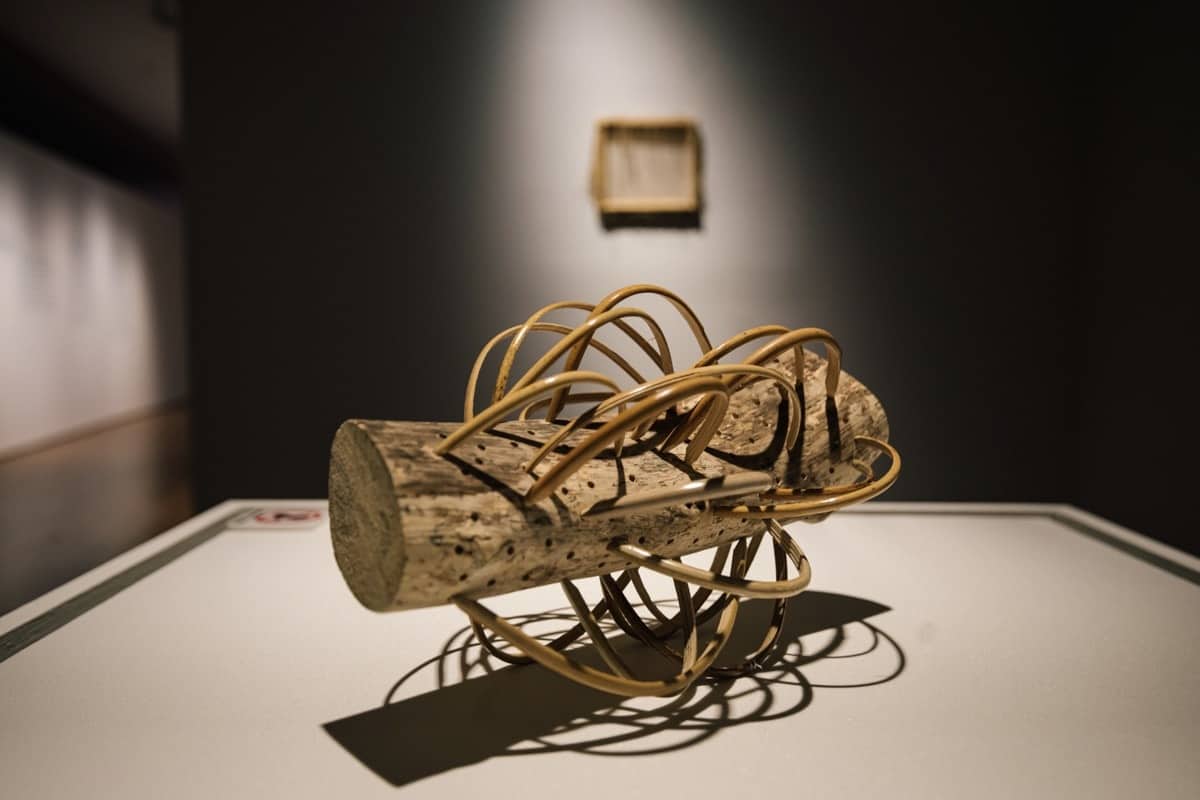

Victor Paul Brang Tun’s Frame(works) (2019) features a series of rattan sculptures that were recreated by deconstructing an old rattan chair. They explore the different ways that a single, discarded item can be reborn in multiple ways, demonstrating the versatility and recyclable nature of rattan and seeming to convey the idea that what many may regard as junk can find rebirth and serve other purposes. These various forms that it takes on are poignant symbols, especially when set in the context of Time Passes, an exhibition featuring works that touch on modes of caring, living and relating in a difficult time like the COVID-19 pandemic. Just as the deconstructed rattan chair represents our altered, possibly frayed, social bonds, its re-creations cast these unwelcome changes in a different light, showing us new ways of caring and relating to each other. As rattan combines with twine, wood and nails to form new sculptures, so can our human bonds navigate and adapt to the new normal.

Junk Art provokes reflection and realisation of the realities that we live in. The works are powerful symbols that awaken us to the innate qualities of everyday items and invite us to look beyond their mere material utility.

_______________________________________

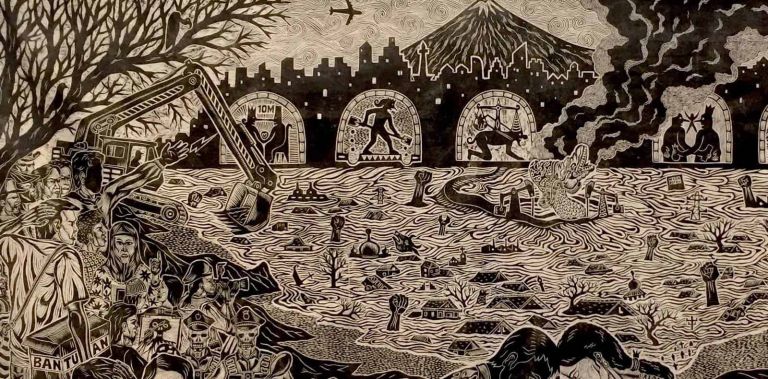

Feature image: Fazleen Karhan, detail of #sgbyecentennial, 2019. Image courtesy of the Singapore Art Museum.

Editor’s note: Like the work by Victor Paul Brang Tun, our feature image artwork by artist Fazleen Karlan can be seen in Time Passes, an exhibition organised by the Singapore Art Museum. The show is part of Proposals for Novel Ways of Being, an initiative in which 12 local art institutions, independent art spaces and collectives join forces in response to a world irrevocably changed by the COVID-19 pandemic.