In a softly lit corridor at the Tate Britain, I find myself encountering the works of late Singaporean artist Kim Lim. Titled Kim Lim: Carving and Printing, this presentation is part of the museum’s Collection Route in an exhibition called British Art 1930 – Now. Surrounded by many well-known artists of the past 90 years, the experience that awaits the viewer is a minimalist display of some of Kim’s works from the 1960s and 70s.

In this space of silence and thoughtful solitude, the rest of the museum fades away, and all that’s left is to appreciate the works that lay before you. There are many ways to unpack Kim’s complex yet minimal practice, but it is equally important to highlight why Kim Lim and this exhibit of her works is significant.

Born in Singapore in 1936, Kim migrated to Britain in the 1950s. There, she attended Saint Martin’s School of Art and later, the Slade School of Art. Developing her sculptural practice alongside her printmaking, Kim exhibited a great deal in her lifetime and travelled the world frequently, studying ancient civilisations as stimulation for her work.

The limitations of her gender and race were apparent to the artist since early on, as the 70s were a time when female artists were still largely overlooked. For instance, she was the only non-white and female artist to exhibit at the Hayward Annual in 1977. Being Asian, Kim was almost always perceived as being an “other” amongst her British peers. In 1989, she was invited to participate in Hayward Gallery’s group exhibition The Other Story, which presented African and Asian artists practicing in post-war Britain. Rejecting the label of an outsider of the Western, male-dominated art scene, Kim declined the invitation. She said:

“Being female and foreign was never a problem as a student – later, I realised that there was a difference; but what was important in the end was what I did and not where I came from. Race and gender were givens I worked from, perhaps the work does reflect this which is fine, but I did not want to make them an issue.”

In 2018, STPI – Creative Workshop and Gallery showed a body of works by Kim titled Sculpting Light. Because it was a solo exhibition, I was able to reflect on Kim’s work the way one should reflect on minimalist art; non-referentially and purely for its materiality and aestheticism. Similarly, at the Tate show, Kim’s exhibit is presented simply as a snapshot of the works and practice of a skilled sculptor and printmaker. Her identity as a woman is not being spotlit here. This curatorial approach allows the viewer the freedom to contemplate the works unfiltered through gendered lens. That is largely because it is not clustered with other female artists or designated as part of an agenda to boost the number of women it shows, as Tate and many other institutions have recently done. (The Collection exhibition culminates in what it calls a “large display of contemporary art by women artists” that is meant to be reflective of “Tate’s ongoing commitment to increasing representation of women artists” in the institution.)

Using lines and planes in her prints, Kim’s work investigates the spaces in between and the shadows around forms. Her choice of materials, colours, and shapes recall ancient times and far-away lands, as influenced by her explorations of ancient sites in destinations such as Europe, India, China, and Asia. Fascinated by architecture and artefacts, Kim’s practice investigates divergent features of these cultures by borrowing and juxtaposing their organic materials with their geometric forms.

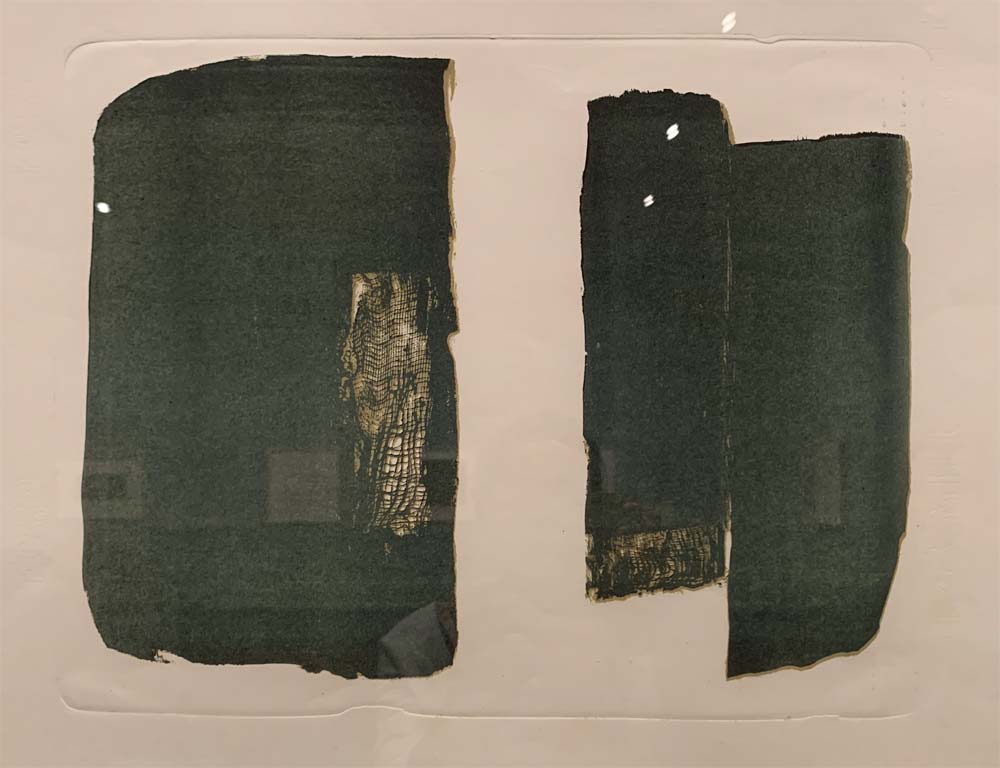

The lithographs Untitled and Split Red are deceiving in that at first glance, the forms on white papers appear to be made of organic cloths. With Untitled, it looks as if Kim tore and separated the fibres of the cloth and then placed it in the middle of the paper. One can probably safely assume that the original was created in that manner. It is only upon closer inspection that it becomes apparent that it is indeed a lithograph, so cleanly executed that it appears almost 3D.

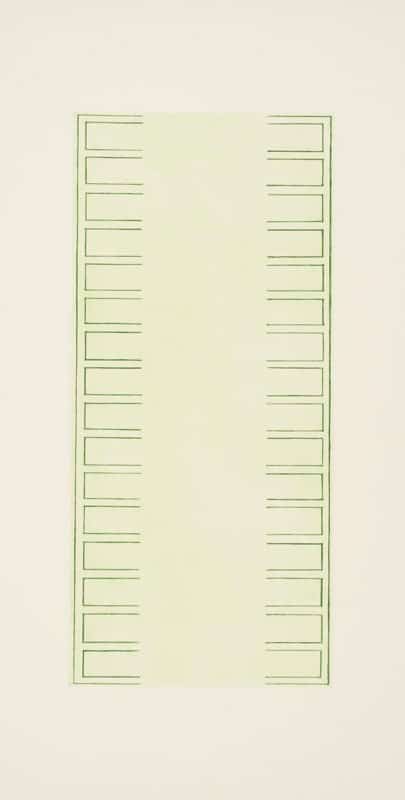

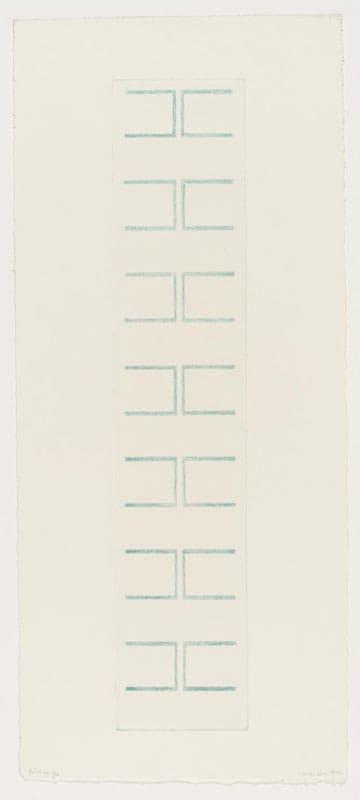

In Ladder Series III, IV and V the negative space makes one wonder which is the artwork: the linear lines that make up the ladder, or the negative space between them? Ladder V feels as if it is vibrating because the lines are not completely smooth as they are in the other Ladder pieces. Rather, they are blurred and partially faded.

Derived from these works on paper are the sculptures Intervals I and II. These pine wood interpretations of the Ladder paper series are remarkable because of the shadows they cast, and because they can be displayed any way one cares to; horizontally, vertically, even at an angle. In any case, the shadows also become part of the artwork.

Kim wrote, “Rhythem [sic] is another preoccupation of mine – the physicality of the feelings of rhythem [sic] makes it very sculptural for me. Using it by repeating a form, a rhythem [sic] is built, which adds to the resonance of a piece.” Ladder Series II exudes that feeling of repetition, a sense that one should expect an indefinite or unending continuation from left to right, as one would read text, of more ladders, expecting them to stretch on unseen into perpetuity.

Kim often drew inspiration from plants, rocks, and bone structure, with wood carving as her preferred medium. She was “constantly amazed by the rhythemic [sic] structures in nature,” and used materials from nature in order to include their characteristics in her work. A good example of this is the sculpture Sphinx, in which she did not paint the wooden parts of the piece as she wanted to preserve its natural aesthetic.

In King and Queen, which are placed together in this exhibit, Kim took a somewhat different approach by casting the wood carvings in bronze and applying patina. This gave the works a richer depth and preserved the graininess of the wood. As with all of the sculptures in the Tate display, Kim’s abstract simplicity and balanced execution evoke a quality reminiscent of eastern spirituality.

To me, Carving and Printing conveys two things: the first is Kim’s practice and her concern with form, space, rhythm, and light. The manner in which she pays as much attention to the voids in her works as the lines and volumes themselves defines her oeuvre. Natural light plays a large role in her works, allowing the creation of shadows in the empty spaces to produce textured effects. Kim said:

“I think of space as a physical substance – to be articulated, manipulated. To be trapped, squeezed by using the forms in a specific way. Using form to punctuate space… Using space as intervals.”

The second significance for me is that this display highlights Kim’s place in history as an artist whose works and practice stand on their own merit. Unquestionably, there is no need to compare and contrast her artworks to that of her white, male counterparts, to mention who her spouse was, or to revise history as a token gesture of inclusion. She may have been Asian and she may have been a woman, but she was, first and foremost, an artist deserving of a place in the art historical canon – as she is finally, truly, attaining now.

______________________

Kim Lim: Carving and Painting is on at Tate Britain, London from now until 5 March 2021.

Feature image: Kim Lim in her studio, 1960. Image credit: Estate of Kim Lim.