The drill is simple, yet it’s one that we can hardly keep in mind. Don’t fool with Mother Nature. And take responsibility for your behaviour towards all species. This is what the pandemic is teaching us, and what Thai artist Ruangsak Anuwatwimon has been speaking about through more than a decade of highly impactful, heartbreaking artworks.

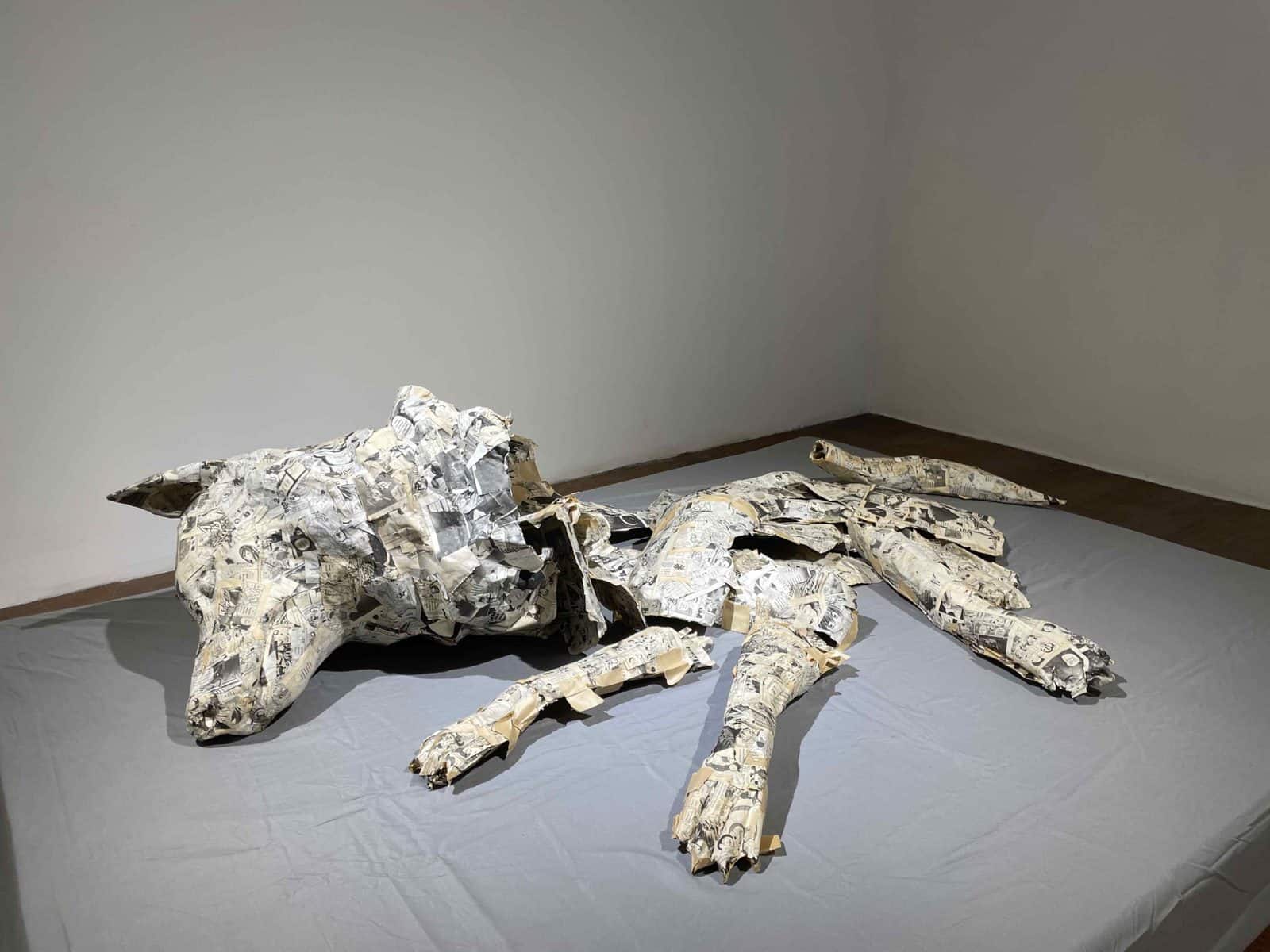

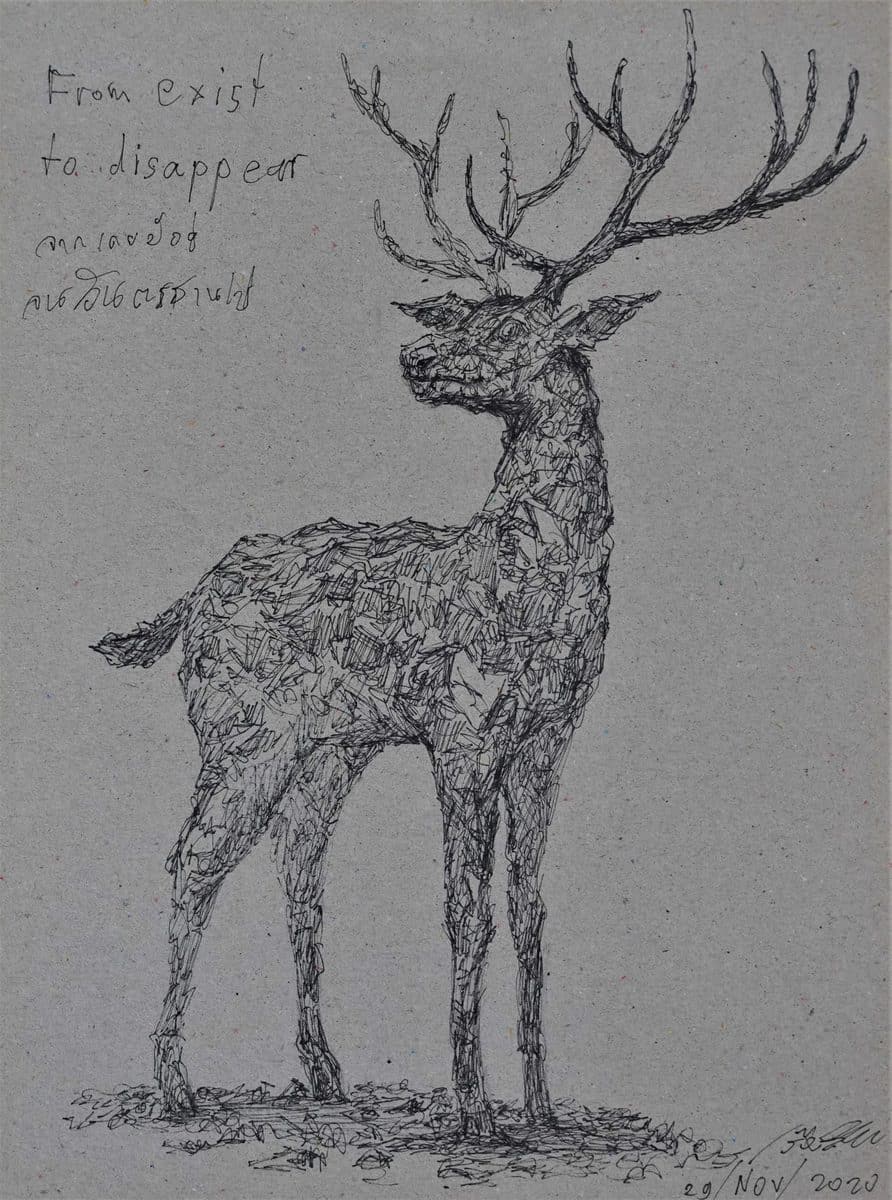

His new show at Warin Lab Contemporary, Bangkok (from May 12 to July 10, 2021) is called Reincarnations III – Ecologies of Life and focuses not only on the impact of the disappearance of animal species, but also the hidden or forgotten national narratives about natural ecosystems. The exhibition features newly-commissioned life-size installations made of newspaper clippings and debris in papier-mâché, representing the extinct Japanese wolf and the Schomburgk’s deer. The show also features a reproduction of the extinct Bhutan glory butterfly.

“I deeply admire Ruangsak’s art practice in its intersection with activism, social justice, and environmentalism,” says the exhibition’s curator Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani, whose focus and research has consistently been on migration and displacement in the face of political changes. When the opportunity to collaborate with Warin Lab Contemporary on environmental topics presented itself, she thought of Ruangsak immediately.

The artist and the curator first collaborated around ten years ago, for an ICA Singapore group show curated by Loredana called “Cut Thru : A View on 21st Century Thai Art”.

“Ruangsak’s work, in particular, was memorable and mesmerizing,” she recalls “Titled the Ash Heart Project the installation presented several suspended sculptures fashioned to resemble human hearts. Each heart was made of the ashes of animal and plant species that had died due to some form of human interaction with the environment.”

I spoke to the artist and the curator for insights into their new show.

Ruangsak, can you please tell us about the genesis of the Reincarnations project, and how your residency at the Centre of Contemporary Art in Kitakyushu, Japan, had an impact on the development of your initial idea?

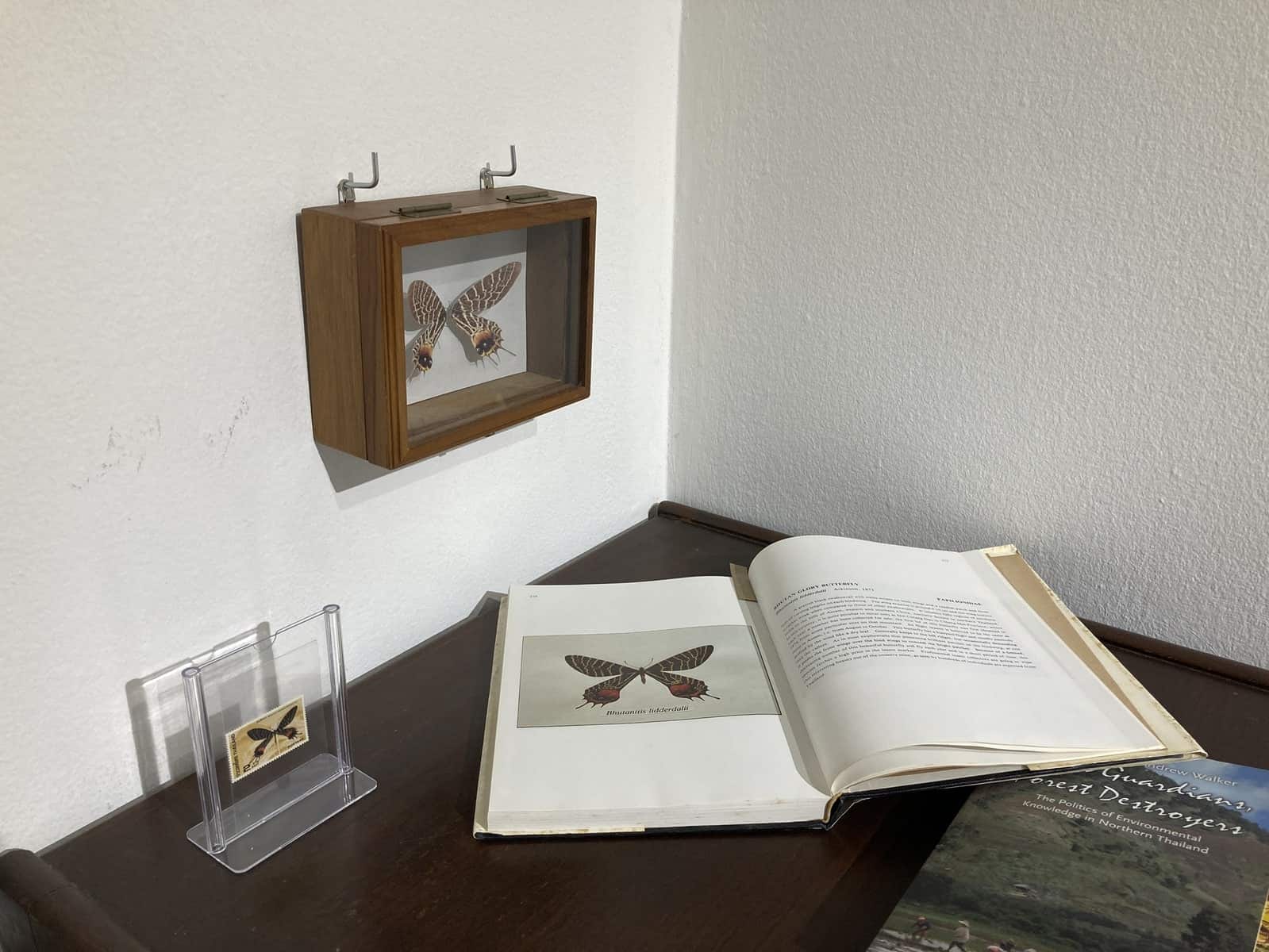

RA: It’s quite a long story which started with my obsession with the story of the Bhutan glory butterfly. This species went extinct just one year before I was born. Around 2012 I asked one friend working in genetics if it was possible to clone (the butterfly). He said it was possible to clone it – although expensive – but we would have to know what kind of plants the insect ate. Since we didn’t have the information, it couldn’t be cloned. However, in 2018 I got the opportunity to do a one-year residency in Japan, and decided to delve deeper into the project.

There, I started developing the project for Reincarnations, as Japan has a huge collection of Bhutan glory butterflies in Tokyo University. Other occurrences pushed me to explore the idea further, including the death of the last male Northern white rhino – there were only three left in the whole world and two were females. That year we also witnessed the mysterious extinction of the Japanese wolf.

The show is not only a denunciation of the disappearance of animal species but also an investigation of the way different narratives enter and exit the public consciousness. How did this concept evolve during the different iterations of the project?

RS: (I learned that) each species doesn’t go extinct so rapidly. In many cases it’s because humans take up natural resources which are necessary to the survival of these animals. But of course, each issue is different depending on the context, and the story is not that linear. For example, the Bhutan glory butterfly’s habitat has been depleted (specifically) due to deforestation and the creation of opium plantations.

I have also investigated how social and environmental issues have been perceived over the last 20 years in Thailand. Decades ago, it was commonplace thinking that the Government or the Ministry of Natural Resources had to be responsible for the use of our resources, but today we realise that it’s up to us as well, to influence social and environmental policies.

Loredana, what is the importance of this exhibition at this particular moment in time?

LP: The ongoing coronavirus emergency has spotlighted the consequences of our precarious attempts to ‘tame’ Mother Nature so this exhibition acquires even more significance in relation to questions on the sustainability of our ecosystem. However, the exhibition also addresses important and ongoing reflections in terms of the economy and distributions of power. On one hand, the project looks at ecologies of life that are in danger of extinction or which are already extinct as a consequence of human actions, and on the other, it highlights the impact of nature and human interaction at the economic and geopolitical levels.

The case of the Schomburgk’s deer, for instance, developed for Reincarnations III is a case in point: native to Thailand, this type of deer was last seen alive in the wild in 1932 and declared extinct in 1938, however, the only embalmed exemplar resides not in Thailand, its home country, but in the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. Adding to its colonial trajectory, this local deer species was named after Sir Robert Schomburgk, who served as British consul in Bangkok from 1857 to 1864.

Left unresearched for many years, it was only in the mid-1960s that the Schomburgk’s deer was acknowledged as an extinct species in Western writing, and accordingly entered into colonial narratives.

The history of the location of Warin Lab Contemporary is also significant. Ruangsak, what are the connections between the site that Warin Lab Contemporary occupies, and this extinct species?

RA: When Loredana first proposed to exhibit in this space, I didn’t realize immediately how connected it was to the Reincarnations project. I later discovered that amongst other things, the venue was once the house of Dr. Boonsong Lekagul, a Thai medical doctor, biologist, ornithologist, herpetologist, and conservationist, who was one of the first to fight to preserve wildlife in Thailand. In the 1950s and 60s, he also produced and collected several books on wildlife, including the Schomburgk’s deer.

Loredana, what has been the biggest challenge in setting up Reincarnations III?

LP: I was familiar with most of Ruangsak’s previous works and in particular with his work for the Singapore Biennale 2019, which was part of the ongoing Reincarnations project. So when he mentioned that he was keen to develop Reincarnations III for Warin Lab Contemporary I was very excited. At the same time, I also realized that I had to learn a lot about animal species and the environment in order for me to develop this project with the artist. This in itself was a challenge, because, despite my interest and dedication to natural matters and their intersection with recorded mainstream histories, my knowledge at the scientific level was very limited compared to the artist. So, I started studying and documenting things for myself.

You went on a field trip with Ruangsak to Rangsit City to research the lost natural habit of the Schomburgk’s deer. Can you tell us about that experience?

LP: The trip had been postponed several times due to the flaring up of new COVID clusters, so that was an additional challenge specific to this particular time in human history. When it finally happened, the site visit to Rangsit provided me with a great opportunity to interact in a physical way with the environment that this particular deer species had inhabited in the 20th century. Sadly, today it is no longer the same as it used to be. In fact, while investigating, we came to realise that many other species had disappeared too, often leaving few traces in natural history books, thereby posing the bigger question of who owns and writes history.

Indeed the different narratives around extinction and ecology are a big focus of the art exhibition. Being narrative-makers themselves, what are the responsibilities of curators in the art world?

LP: As I wrote in an article a few months ago on art and the environment, artists and curators around the world have been taking collective action in raising awareness on environmental threats. As Lucy Lippard discusses in her book Undermining: A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West, subversion is one way in which artists can resist acts of greed and inequity which harm the environment

As a curator, I feel it is part of my ethical call to discuss these complex issues through art as a tool for social activism and collective support.

Ruangsak, after years of working as an artist-activist, have you drawn any new conclusions about the role that artists can have in effecting social change?

RA: It’s difficult to say! In my opinion, an artist alone can’t possibly portray all the (relevant) information with balance. I have also been questioned about the actual results on policies that artists can have through their work. However, I feel it’s not about the results per se, but rather about opening a space for dialogue and criticism on how things have been done so far. It’s about researching and investigating areas that no one pays attention to. But do we still have hope for the future? Yes! While Reincarnations deals mostly with the past and present states of the environment, I feel that the enhancing of our awareness will also (help to) shape our future.

_________________________________________

Reincarnations III – Ecologies of Life is presently showing at Warin Lab Contemporary, Bangkok till July 10, 2021. We urge all readers to visit responsibly and in line with existing pandemic management measures.