The Asian Civilisations Museum opened its #SGFASHIONNOW exhibition this week on 25 June, its very first show on contemporary Singapore fashion. It’s been produced in collaboration with LASALLE College of the Arts and includes a winning design from the Textiles and Fashion Federation’s (TaFF) Singapore Stories design competition in 2020.

In the lead-up to this milestone event, we caught up with ACM Director Kennie Ting on his impeccable personal sense of style, his professional journey, and his thoughts on the role of museums today.

Hello Kennie! Tell us more about your interest in fashion – where does it come from and what drives it?

In general, I am just very interested in the visuals of beautiful things. Visuals offer a powerful way of communicating, and I’m genuinely quite careful, and very particular about what I wear not just at events, but also on a day-to-day level at work.

Do you have a favourite designer or a favourite kind of aesthetic?

I have a favourite kind of aesthetic in two ways. One that’s very conceptual, and one that’s very literal. So literally, I love all kinds of floral anything. Even when I’m very formal in a suit, I will always have a floral tie, or pocket square.

But then conceptually, what I like is this idea of the ‘radically classic.’ So I like dressing very classically in traditional forms – a suit and bow tie, or the tangzhuang or the kurta, or the Japanese happi. But, I’ll give it a radical take, making the very subversive point that ‘old’ is the new ‘new.’

Does this thinking feed into your work as a museum head?

In my other life, I’m actually a writer and photographer and I’ve written books about port cities, grand hotels, and the history of luxury travel. I love the 1920s so part of my aesthetic is always about reaching back to the 1920s in all its forms and looking at how that can be radically updated for today. Whether it’s the three-piece suits, or the sense of grandeur and travel with the ports, steamships, trains and aeroplanes – I try very hard to translate all this into what I wear, which then in turn feeds into a sense of how I run the museum as well.

What about the 1920s is so attractive to you?

I’m fascinated with the 1920s in Asia specifically, and with port cities like Shanghai and Bombay (Mumbai), with their sense of style and their sense of the infinitely possible. These days, it’s a bit politically incorrect to have a sense of nostalgia about all that, but its aesthetic offers the ability to appreciate life in its fullest forms. It also offers an ability to appreciate quality, because everything that was worn then, was made by someone. And I think that’s very important. Everything that I like to wear is more or less made in Singapore, or in Asia, and in the image of those halcyon days, the golden age of travel. I feel that in Asia – COVID notwithstanding – it’s a golden age for us right now. The world is turning our way and we should assimilate our past and make it our own. There’s a lot of joy to be found in mining the past for its imagery, culture and its sense of abandon.

Do you look for vintage pieces in particular? How does sustainability feature in your forays into fashion?

For me, what’s most important is cultural sustainability and the question of how we champion the fact that craft in Asia has had a long tradition. Fashion design has been very Western-oriented in the last century, and it’s important today, to find ways to sustain craft practices. Part of that might include environmental sustainability, although what’s also important is the sustaining of communities which make things, because the process of making things itself is rooted in heritage of all forms. In buying and wearing clothes by local or Asian designers, I’m hopefully throwing light onto the sustainability of communities of craft. I would argue also, that if we’re talking about environmental sustainability, even if this (link) is a bit tenuous, that if we revert to these ideas of communities of craft rather than fast fashion, we would greatly reduce levels of environmental unsustainability in the fashion industry.

How important do you think it is for museum heads to be the public faces of their organisations? Do you think it’s important for them to have interesting public personae and present themselves well?

Yes! That is my job as the director of the museum. I take on the job knowing full well that that my team and I represent the human face of the museum. The responsibility is on my shoulders to represent the institution in its best form to everybody – to the public, to the press, to our donors and to our patrons. I know that I have a role to play and I think that role is very important in terms of adding softness to what is essentially a collection of very hard things, buildings and objects.

How do I choose what to wear? Very carefully.

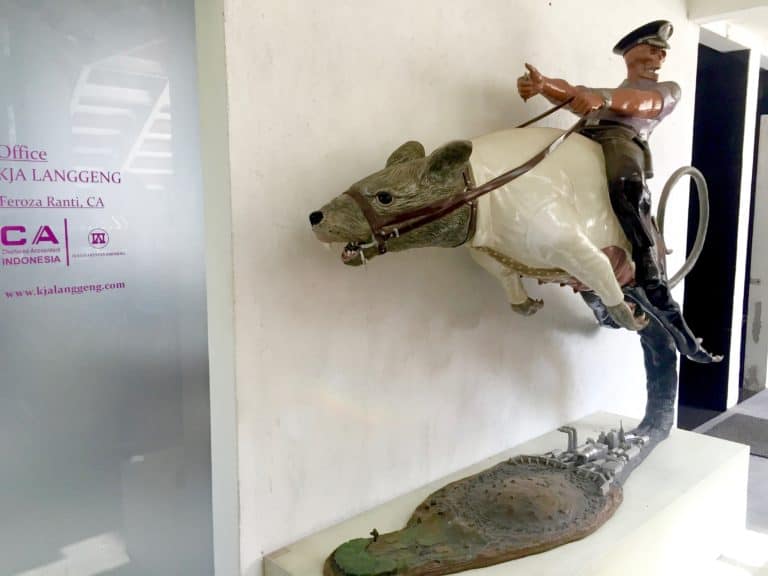

Our last formal exhibition launch was for the Dr Tan Tsze Chor Living with Ink show, and because I knew already that we were going into the space of Singapore fashion, I started exploring the question of what Singapore fashion actually is. This (extreme left, below) is an example of my ‘radical classic’ aesthetic:

There’s also a point to be made about dressing formally. And you know what, people enjoy dressing up! There is very little opportunity in Singapore for people to be dressed to the nines for events, and we want to create a sense of occasion. And so for all of those reasons, I always think very carefully about what I’m dressed in, and about the kinds of dress codes that we have for our events. Our funders took some convincing as well. I remember when I first started, some people from the Ministry showed up at an event where I was wearing my suit and bow tie. They said, “Wah, going to casino ah?” And I said “No! It’s the dress code.”

You can’t just show up after work at the office, you’ve got to actually dress up and come (to the ACM)! I joke about this, but again, it’s important because this also helps to support the industry. We need to have these kinds of events where there is a sense of occasion to dress up, in order to have an industry of fashion.

How do you balance this sense of occasion with the idea that the museum also has to be an accessible place?

Well, we have different kinds of exhibitions and programmes for different target segments. Openings are more formal and diplomatic – they’re for patrons, that’s very clear, because they’re events to show funders that we need their help.

For each exhibition, there is always a package of offerings that all segments of the Singaporean audience are able to enjoy. For example, with the fashion exhibitions, the very first preview is always for the fashion community and industry at large and for every exhibition, there’s an international academic symposium, for the academics. Our (upcoming) fashion exhibition will be targeted towards a younger audience. But we also have things like the upcoming Ming Dynasty exhibition with Beijing’s Palace Museum that was planned with the older generation in mind, and our Living with Ink show, which was very popular with the Chinese-speaking community. Our (more casual) family programmes are immensely popular, and we have interactive spaces within our exhibition that are free for all to access.

You’re the youngest museum director ever appointed by the ACM. Do you struggle with the sense that people may not take you seriously because you come across as too young? Or too frivolous in the way that you dress?

The reason why I decided to make my dressing something so important, was firstly, because I wanted people to take me seriously. But there’s always a twist to this, right, in my ‘radical classic’ aesthetic. I’m the youngest museum director, but in my dressing I’m reaching back to a far older past. This way of dressing is also a weapon – it’s my Batman suit!

There’s the real me – scared, terrified at the time – of dealing with people who were very experienced and in their 60s. And I didn’t just show up as the museum director, I also took on the obligations that came with it. For example, I had to chair an international organisation with the directors of the British Museum. So even when I’m in a formal suit, I’m always dressed in something that’s floral, because I feel that even if I’m putting on this ‘Batsuit’ to be taken seriously, there should still be a bit of myself in it.

You know, whenever I have to make a difficult decision, or chair a difficult meeting, I will always be in roses. You know why? You might think if you see the roses, that I’ll be easygoing, but actually, roses have thorns!

Could you share your struggles and the way you overcome them? Is there any guidance you have for people in a similar position?

In the first year when I took over the museum, we were moving from a very classic Asian art museum to (what it is now). We were disrupting the general museum theme and there was a lot of animosity that I had to face across the board from some of our patrons and docents – those who were closest to us. There was a sense that I came out of nowhere, and not from the ‘museum world’. There were many more experienced people in the industry who could have taken this job. And so, a lot of my time was spent just trying to fob off people who were telling me what to do. It was very hard because at the time I couldn’t have a conversation with anyone without them saying “you need to do this or that” or “you need to bring back the old ACM.”

Those kinds of conversations were disheartening but I took on board what I felt was important. At the same time I had to stick to my guns and also make the point that I was different. I’m not my predecessors and I’m not like anyone else here.

It was important for me to present myself as me, wearing suits in meetings to show that I meant business, but also with things like quirky bow ties to add softness and to just remind myself not to take things too seriously. After a health scare last year where I almost died, I feel all the more that I need to be seen as full of life.

Are there any other institutions that you look to for inspiration?

My favourite museum in the world (well aside from the ACM) is the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London. It started off as a trade museum for industry and to support local trade. (Of course ‘local’ at the time meant the whole colonial empire so admittedly there is a dark side to it as well.) With this kind of broad thinking, I knew for example that we didn’t just want to do a fashion exhibition, it had to be an initiative that was tied in with the trade today, and that’s not new, the V&A started off that way. Today though, we run into questions of commercialism, and whether we’re flirting with it when we work with practising designers.

In fact, to be featured in #SGFASHIONNOW, one condition is that you still have to have your business going. And that is a radical shift in terms of the role that a museum ought to play. In response to that, I say that a museum needs to be a platform for the development of young talent, whatever era that might be. In some ways, there is no difference between this, and how contemporary art museums feature contemporary artists.

Of course, in working with living and practising designers, it is always at the top of our minds, that there should be a link back to the museum’s collections, as a public good. This is a way of encouraging greater use of these collections, of showing that they’re not just there to tell us about history and culture. My dream is that we would have designers or businesses creating new products that are wildly successful, inspired by our heritage, which is in turn embodied in the museum’s collections.

________________________

#SGFASHIONNOW at the ACM opened to the public on 25 June and runs till 19 December 2021. Find out more on opening hours and programming on their website.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity, all images are courtesy of Kennie Ting and the ACM.