A nail, a safety pin, a pressure cooker. Upon first scrolling through the Objects gallery of Thamizhachi, supposedly composed of everyday items significant to Singaporean Tamil women, my first thought was: perhaps the typical Singaporean Tamil household is not so different from my own after all. Further investigation would prove my initial observation both right and wrong.

While few of the objects showcased in the museum are, in fact, exclusive to Singaporean Tamil households, they nevertheless hold an additional, culturally-specific layer of context in the eyes of Singaporean Tamil women. At the same time, many of the objects in the museum also speak to wider issues in the construction of identity — the complexities of navigating intersection, defining authenticity, and finding balance.

Nail /

ஆணி.

Safety Pin /

காப்பூசி.

Billed as “a digital museum of Tamil women under construction”, Thamizhachi is currently being showcased as a part of T:>Works’ (pronounced Theatreworks) N.O.W 2021, a three-week-long Festival of Women. The title comes from the Tamil word thamizhachi, which is a combination of “Thamizh” (Tamil) and the feminine suffix “-achi”, denoting Tamil women. The term itself is one of the “objects” featured in the digital museum, and is described as carrying a variety of connotations, from a woman who is “(overly)traditional and homely” to “unruly”. It aptly captures the essence of how identity exists not as a static concept but a constantly shifting, lived reality – a theme that runs throughout the whole museum.

The museum is a project by Brown Voices, a collective of Indian theatre practitioners that aims to “generate and encourage narratives expressing the perspectives, concerns, and aspirations of Singaporean Indians”. In line with this philosophy, Thamizhachi was designed for Tamil women themselves to explore how they are “imagined, illustrated, identified, deliberated, disputed, displayed, collected, curated, constructed”.

The museum consists of two main galleries: Objects and Persons, put together through a series of consultative workshops with 22 participants, all of whom self-identify as Singaporean Tamil women. All 22 participants and additional collaborators responsible for bringing Thamizhachi to life are featured in the Persons gallery. They are a diverse cast of women, ranging from fresh university graduates to retirees, from a variety of professional, religious, and even racial backgrounds.

Each individual has their own profile page, where you can find their name, age, and profession, along with a short biography. Although the Persons gallery comes after the Objects gallery on the webpage, I found it more instructive to peruse the Persons gallery first, to get a better sense of the women behind the voices who speak so passionately of the items in the Objects gallery.

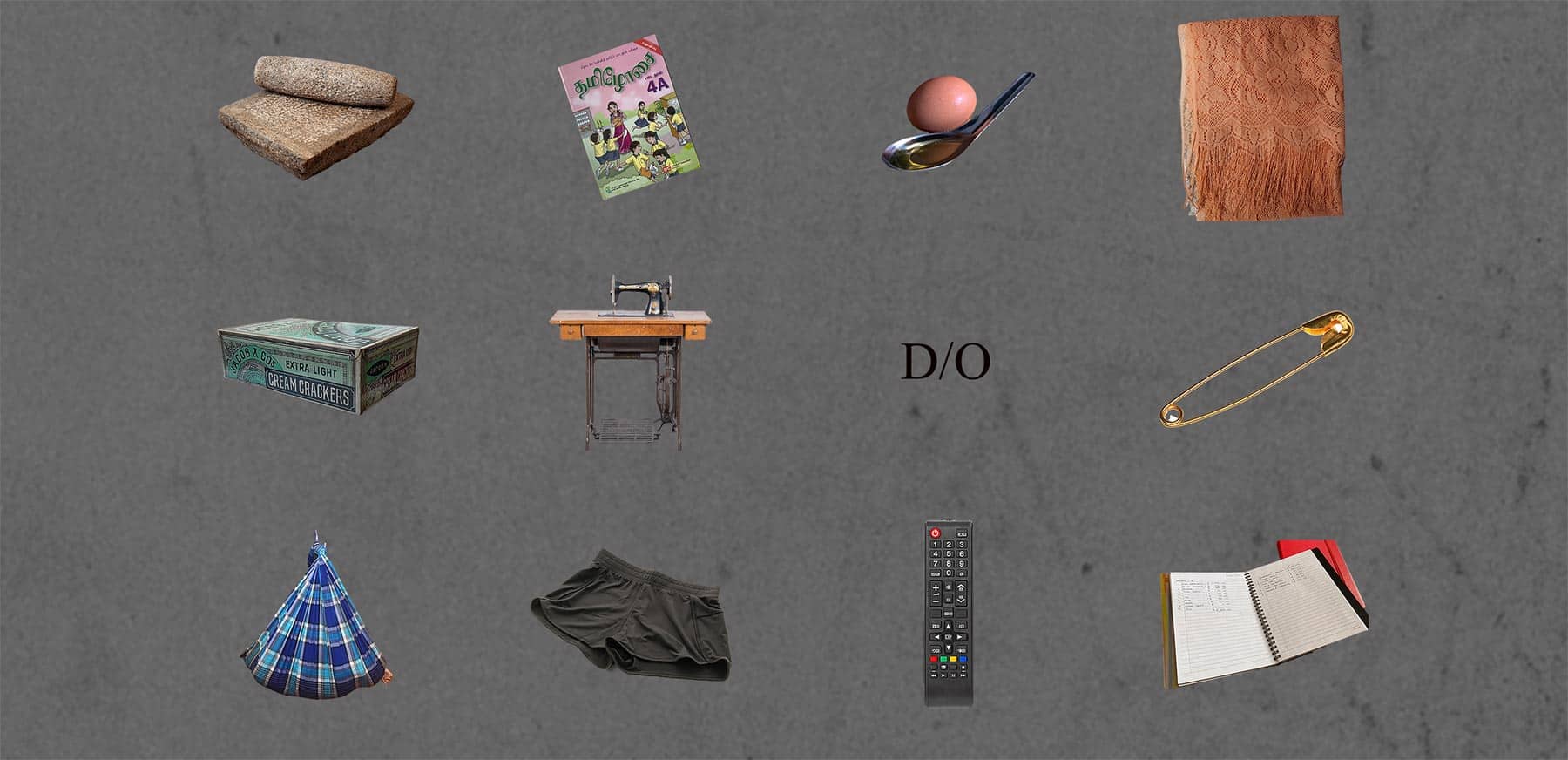

The Objects gallery consists of 29 items that workshop participants identified as commonplace objects central to the formation and understanding of their Thamizhachi identity. Each object in the gallery is featured on its own page, which contains a picture and a brief description of the context of how Singaporean Tamil women tend to use it.

Most interesting, however, is the notes section at the bottom of each Object page, where you can find comments from the workshop participants on what the item means to them personally. It is in these comments that the raw, human voices behind the abstract concept of “identity” breaks through, and the messy, often contradictory, process of identity building is laid bare. Thamizhachi frames itself as a museum under construction, recognising how Thamizhachi as an identity is a work eternally in progress, a never-ending tapestry of woven threads and tangled knots.

In some cases, I came to see and appreciate familiar objects in a new light. The safety pin, for instance, is an indispensable weapon in the sartorial arsenal of Singaporean Tamil women, being the key to keeping a sari secure and its pleats neatly laid. For this reason, many Singaporean Tamil women keep a few on their person at all times, often hanging from their thali (necklace worn by married women). The humble nail is another common object that carries a specific cultural dimension among the Singaporean Tamil community. As a sharp object, it is believed to ward off supernatural beings. Women are thus advised to carry it as a protective charm, especially when they are thought to be particularly vulnerable, such as during their period or while carrying potent items like meat. As a Singaporean Chinese, I found it both educational and enjoyable to learn about the ways in which we are “same same, but different”.

But learning about the cultural differences goes beyond simply discovering interesting customs and beliefs; it includes understanding and acknowledging the unique challenges another community may struggle with. The term “D/O”, for example, exposes the difficulties Singaporean Tamil women face when trying to establish their Thamizhachi identity in the wider world.

The term “D/O”, which stands for “daughter of”, originated as a convention of colonial administration to use in place of a surname for Tamil Hindu women. Although it continues to be commonly used, many of Singapore’s state institutions do not have the proper infrastructure to recognise it. As a result, Singaporean Tamil women often find the “/” being rejected or incorrectly substituted by “do” on computer systems, and face a dilemma in filling up forms with a “first name” and “last name” column. While this may be a minor inconvenience in the larger scheme of things, such unthinking erasure nevertheless demonstrates the fundamental absence of consideration of issues that Singaporean Tamils have to deal with in living as a minority in a country they call home. It is a powerful reminder of the mundane ways in which privilege silently asserts itself, confronting visitors to re-evaluate the lines along which the categories of the “default” and the “norm” are drawn.

On the whole, however, much of the gallery evokes conversations around broader issues of identity-building that are applicable to anyone, such as the tension between tradition and modernity. Domestic items such as the grinding stone (‘ammikal’), pressure cooker, and aluminium pot were met with conflicting responses among Thamizhachi’s participants. Some felt they were symbolic of women’s central, traditional role in the areas of food and family, while others complained they reinforced the outdated link between women and the domestic sphere.

Commenting on the pressure cooker, for instance, participant Shanti declares that it “represents women’s freedom. Because of the pressure cooker, women spent less time cooking, and got freedom from the kitchen…”. In direct opposition, Azhagulina bemoans, “Why do women have to have such a stereotypically domestic storyline?”. There is evidently no easy or straightforward interpretation as to what the “right” balance between tradition and modern-day feminism should be in defining Thamizhachi. Curiously, this juggling act between past and present seems to be tied particularly to femininity and womanhood, as women are generalised as the “bearers of tradition” in many cultures.

Apart from gender, aspects such as religion and race can also intersect in our understandings of authenticity and legitimacy in identity. With most Tamils in Singapore being Hindu, people tend forget there are Muslim and Christian/Catholic Tamils as well. Participant Nasihah admits that she is “more than happy to be mistaken for a Malay lady” around Tamil-speaking Muslims so as to avoid conversations about marriage and children, nonetheless revealing that not even those within the Muslim Tamil community are immune to making assumptions about race based on religion.

Other participants are less comfortable with such ambiguity, however. Talking about the lace headscarf worn by Muslim Tamil women, Sofia insists, “My religious identity cannot be separated from my Tamil-ness”. Megan echoed a similar sentiment when she commented on the statue of St Anne, saying, “I cannot separate my Tamil identity from my Catholic identity”. But it is not easy navigating between multiple facets of identity. Although Megan enjoys Annamma Pongal as one of the few times where she feels “most able to claim (her) Tamil heritage” by honouring her culture, religion, and family history all at once, she calls her family celebrations “fake Pongal” when speaking to her Hindu Tamil friends who celebrate the festival differently. We thus see how identity consists of many layers which converge and mix, adding further shades of nuance to an already nebulous concept.

Looking through the Persons and Objects galleries, the diversity of Singapore’s Thamizhachi is evident and it becomes clear that a universal, shared cultural background does not automatically equate to a universal identity. Thamizhachi succeeds most admirably in its mission to create a museum that “consciously refuse(s) essentialised, homogenised, and/or tokenistic representations of the diverse ways of being a Singaporean Tamil woman”. At the same time, there are broader themes, within the process of identity-building itself, that resonate and find home with a wider audience far beyond the Thamizhachi community.

In this era of post-colonialism and globalisation, there have been calls to reimagine the ethnographic museum as a “contact zone” where curators and the community acknowledge and actively negotiate issues of history and representation. The consultative nature of Thamizhachi’s construction, the presence of the participants’ comments in the notes section, and the invitation for guests to add their own comments and provide object suggestions, all demonstrate the potential of future ethnographic museums to act as such contact zones where discourse can come to life. As the concept of intersectionality enters the mainstream of social and political activism, the development of such platforms for representation is timelier than ever.

—

Thamizachi is on view until 31 July 2021 as part of the N.O.W. 2021 festival. Are you a Singaporean Tamil woman? If so, you are invited to participate in project by suggesting an object that is part of and/or animates the life of a Singaporean Tamil Woman here (scroll to the form after the section on Objects).

In conjunction with Thamizhachi, Brown Voices will also be presenting a live-streamed performance, Rasanai: An Invitation to Appreciate on 24 July. Tickets are available on the website.

All images are courtesy of T:>Works.