Two months ago, I caught the second installation of the WLG Incubator Young Artists Show 2021, held in Kuala Lumpur (KL), Malaysia. Organised by Wei-Ling Gallery, the project aims to nurture and highlight emerging Malaysian artists through a mentorship programme with more established artists, giving these emerging talents the opportunity to develop and show their work. This year’s incubator featured artists Alya Hatta, Anwar Suhaimi and Shika.

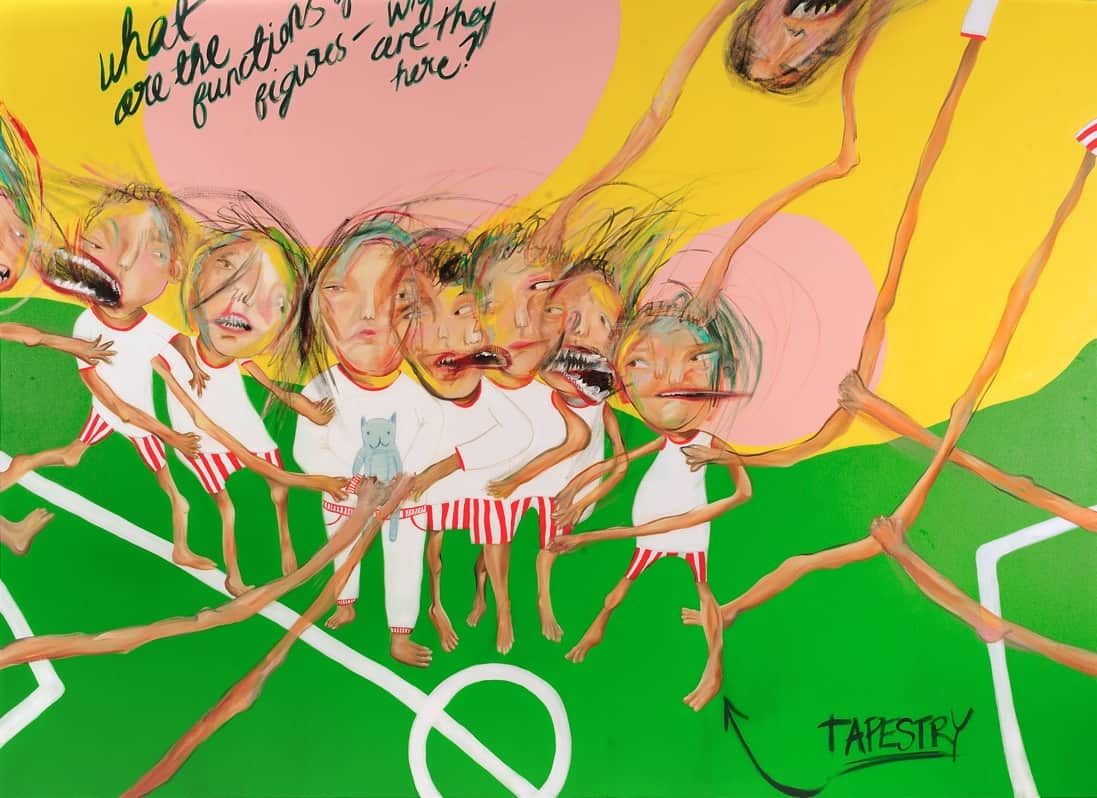

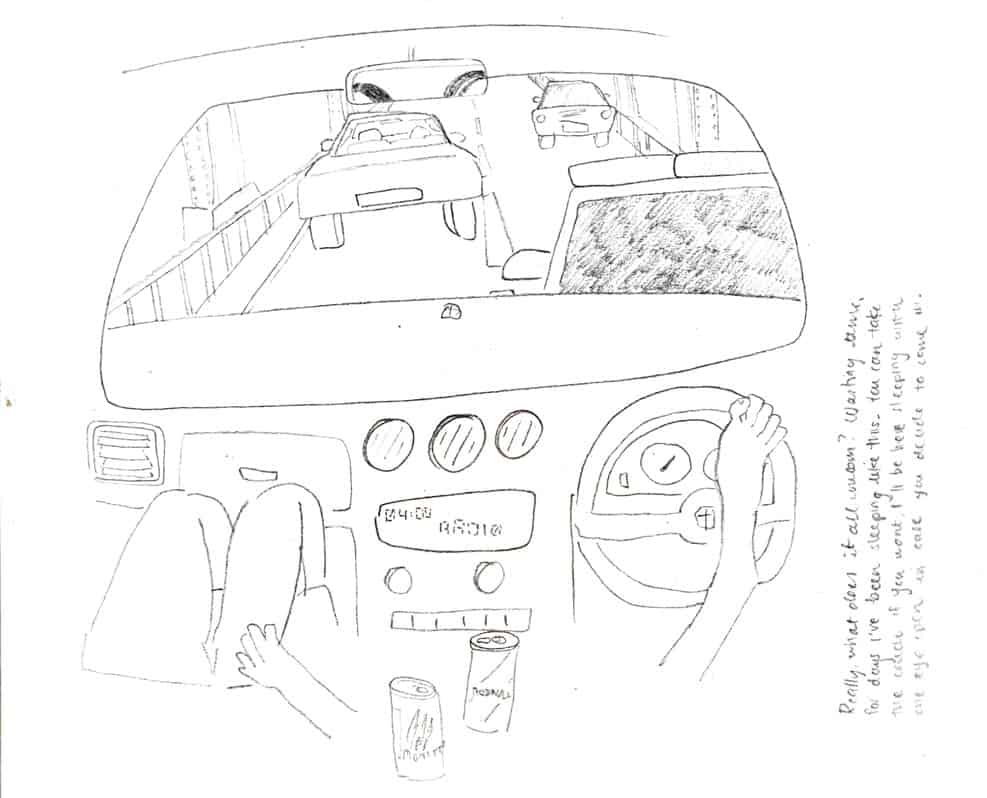

Months after the show, I found myself continuing to think about London-based artist Alya Hatta’s series Always Greener, with its striking soft sculpture, small diaristic works of pencil on paper, and large canvases filled with bright colours and intimate scenes.

In particular, her images of the female figures stayed with me.

The women in Alya’s work are often nude or seminude. Their breasts are asymmetrical, their bellies round and their love handles rest on their waistbands. This unfiltered exhibitionism is perhaps best captured in the soft sculpture Sleaze Cake:

To me, looking at these women felt like the act of peering into a private world. One where the male gaze and its attendant pressures to minimise the female body, are absent.

In my conversation with the artist, we talked about her search for identity through her art, the pressures felt by women to look a certain way, and how her process as an artist has evolved over time.

You were recently part of the Wei-Ling Gallery Incubator Young Artists Show, which included mentorship by Anurendra Jegadeva. What was that like?

It was really, really valuable talking to Anu, because of his experience. What I got from him most, was the idea that I should do whatever it is I want. I think a lot of times, within the Malaysian art context, I tend to tiptoe around certain things. Or, I’m unsure as to whether certain things are going to be okay. Or if people will be okay with them. I think because (Anu’s) older and he’s also a guy, he’s very used to just doing whatever the fuck he wants, and not even thinking about what other people think. That attitude really inspired me to just go for it.

Also, the gallery process– I did not expect that a gallery would pay for my shipping costs from London to KL. Someone just showed up at my door to take my works to Malaysia. In terms of the curatorial process, it was very nice to work with the gallery, because I was allowed to just focus on creating the work.

It’s not your first show. You’ve done a solo exhibition in Malaysia and you’ve been part of group shows before. How is this exhibition different from your previous work?

I’ve been more hands-on with curating in previous shows. I might have been (more similarly invoved) if I was in Malaysia, who knows? But I think the distance also made me aware that I don’t really have to do any of that extra stuff, and can just focus on making the work. Also, when I read Amanda Ariawan’s exhibition text written about my work, I was just like, “Oh, yeah, this is better than what I could ever have done.”

I was interested in how the exhibition is about an exploration of the representation of your Asian identity, displacement and diaspora. Have you always been interested in these themes?

I was born in Malaysia, but when I was one I moved to Indonesia. And then I moved to Saudi Arabia, to Dubai, to London, and then back to Dubai, and back to Malaysia, and now London again. I want to make art, but I’ve never known what to make art about. I constantly found myself trying to define my identity. Over the years, just because it was so hard to pinpoint a part of my identity that I wanted to make work about, I came to realise that my work was actually about the search for identity.

Has your expression of that search for identity changed over time?

At Goldsmiths College (where I did my BA), it’s all very conceptual, even pseudo-conceptual. I got there and everyone was throwing these Western philosophers in my face. I was trying to catch up you know, thinking that I was supposed to know who Heidegger and Kant are. I was really confused and thought I was going to have to read all these essays. So I started reading essays about Southeast Asian politics and analysis into colonialism, but then I realised that I don’t even like to read. I hate theory! It was making my work a bit dead. So I started from that point, and then I started to shift. Rather than having to do all that stuff, I asked why I didn’t just look within myself? Because I think that was what was missing in my practice – a sense of self.

So I began calling my family, saying thing like “Nenek (grandma), tell me about what you were doing back in those days? What was the worst thing that happened to you; or, the funniest thing you did when you were younger?”

I knew my grandma and my mom, but I didn’t really know them. Who were they before me? I had no idea. So I started doing small forms of research like that, which I genuinely enjoyed. Looking at my own environment, taking my experiences of things like racism, or sexism that exist here in the United Kingdom (UK)—that became my research bank. I even looked to stupid photos of my friends on my phone.

Don’t get me wrong, I still do the reading. But now, I only read things that I like.

I was struck in the smaller pieces in the show, by how diaristic they are. They’re like private scenes and I was especially struck in this show by the female figures in your work. They’re often in a state of undress, and look natural. Their breasts are saggy, they have love handles, you can see the folds of their skin. It felt like a very uninhibited depiction of women’s bodies. Were you thinking about how to depict women’s bodies in your work?

I think first of all they’re always Asian women to me. I’m literally five foot eleven while my friends around me in Malaysia were five foot two. I remember that someone called me ‘the Hulk’ one time [laughs]. I laugh now, but I had an eating disorder while growing up. And I’ve had body dysmorphia since then. So I’ve always had a strained relationship with my body since around the age of eight. I was also the only Asian in my class when I was in the UK.

I paint people in the way that I do because people should just look however they want. I also think about what is “normal”? There shouldn’t be a fixed idea of what is “normal”. Let me have all the lumps and bumps. I just paint bearing in mind the kind of energy that I’m having on that day and what it’s getting me to do. But it’s important for me that none of my figures look like what people think a woman should look like.

I want to unpack that, what a woman should look like. When I shared a picture of the soft sculpture on my Insta stories, my friend who’s a mum replied, and said, “Oh, that looks like my body.” She was being self-deprecating about it, but that is what makes it so interesting to me. Because that sculpture is not meant to look realistic. It’s exaggerated in its features but at the same time, that is kind of what women’s bodies look like, you know? Sometimes you do have one boob that goes that way. Something about it felt really honest about women’s bodies. What led you to use that particular form?

I use myself, but not as a model. I’m so hyper-aware of how my body is in every state of being because of my own personal problems. I feel every part of my clothing stick to every part of my body. It’s like a constant adjustment and checking of yourself. I wanted (the sculpture) to look like what I felt like. The manufacturer of the inflatable, Studio Souffle, is owned by two women, one of whom is Malaysian, and I’m sure that they too understand this whole pressure about women’s bodies. So, I was clear that there needed to be a back roll, and that the ass had to be falling down, and that the titties were like this. Let’s just be real, you can be any size but whose body is going to be like any of those girls on Instagram, you know? That’s so fake.

The Sleaze Cake sculpture is an inflatable and there’s an aspect of it that’s both like a sex doll and not a sex doll all at the same time. Was that something that you were playing with?

I was initially thinking about the ideas of play– of inflatable castles and bouncy castles when we’re younger, but over time, how the idea of play morphs into sexual stuff. And it just reminded me of the number of times I’ve been fetishised as an Asian woman. I think [the] material qualities of an inflatable are fun no matter what. I think you can look at that inflatable piece and see that it’s still cute.

Looking to the future, what are you working on now ?

I’m doing a solo show in Milan in February 2022. Now that I’m at the Royal College of Art (pursuing an MA) I’ve just completely changed my way of working. I went from reading all these essays to the complete opposite, where I just didn’t think, but did stuff instead. I have been to so many more art shows this year, just looking at really sick artists, the ones that I’ve always looked up to. Right now, I’m actually looking at techniques, materials, processes, and especially the materiality of paint. I’m considering how I can push that thinking more –how I can layer colours with different opacities, using different washes, and things like that. My themes have also changed a bit. I’ve definitely gone more into Southeast Asian myth, generational tales and things that are passed down. Rather than just representing the life around me, I ask myself how I can go beyond that and think about alternative realities that may or may not exist.

____________________________________

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You can find out more about Alya Hatta’s art practice here – https://www.hatta.studio/About-Alya