The first thing that hits you about the art gallery Mr Lim’s Shop of Visual Treasures is its quirky, kitschy name. It’s perhaps a cocky move for a gallerist to describe their works from the get-go as ‘visual treasures,’ but the name of the space fits right in with the larger-than-life personality of Mr Lim Chiao Woon, the gallery’s founder.

On the day that I arrive for my visit to the gallery, now located in Haji Lane, Lim is showing a pair of tourists around. The space is narrow and there isn’t much room to manoeuvre but his excitement and the tourists’ keen interest are palpable.

We sit down to start our chat and it shocks me as we kick things off when Lim blithely announces, “Before we proceed I need to tell you something—I’m actually blind, so please excuse me if I don’t look you directly in the eye.”

He explains that a bout of lymphoma has impaired his vision very severely and that he can only make out the vaguest of shapes at times. It is staggering to hear this as we have been emailing each other back and forth, and Lim has given no indication of his condition as he showed his customers around the shop. He later tells me that he has a “very small pinhole vision, and some peripheral vision” so he can see “sides and bottoms.”

A senior ad man for around 23 to 24 years, Lim quit his job after his serious medical diagnosis which resulted in the growth of a tumour on top of his heart.

He laughingly tells me that “work is toxic, it’s carcinogenic. There’s a reason why they give you money, it’s because you have to take poison.”

After more than 20 years of shopping as an art collector with “Banksys, old Murakamis and Shepard Faireys” (amongst others) in his personal collection, Lim found an affordable space in the now-closed Tanglin Shopping Centre. There, he opened a small 330 sq ft-sized gallery in 2021 to sell his personal collection of art. The shop has an online presence as well, and through introductions by local art luminaries like Woon Tien Wei and Cheo Chai Hiang, Lim was able to meet young artists to add to his stable of talent.

A shop of visual treasures run by a blind man

The first thing that jumps out at me when we start our chat is Lim’s open declaration that he seeks to support and represent promising but less-advantaged artists.

“When I started meeting local artists, I found that a number of them would just give up after say, three years, because it’s just impossible. It’s very, very hard,” he says.

“If you’re a young kid and from a loaded family, then you’re fine,” he continues, “you might be able to do this for fifteen to twenty years, no problem. You can have your art practice and you might even end up in a Biennale.”

“But if you’re not, by the second year, you find a boyfriend or a girlfriend and you get married, the HDB comes, you take out a five hundred grand loan, and you’ll need a day job. With day jobs, some artists find it so hard to paint properly because even as an art teacher, you’d end the day at 6 or 7pm. [By that time] you only have the energy to watch Netflix and then you fall asleep,” he sighs.

Au fait with the stresses faced by young artists, Lim shares that although he takes a commission for sales, “because there is rent to pay,” the bulk of the gallery’s funding comes from his own savings. Nonetheless, he doesn’t bind artists in complicated contracts and they are free to go anytime they want. Sometimes Lim assists with contractual reviews if he feels that his artists are in danger of “being ripped off.”

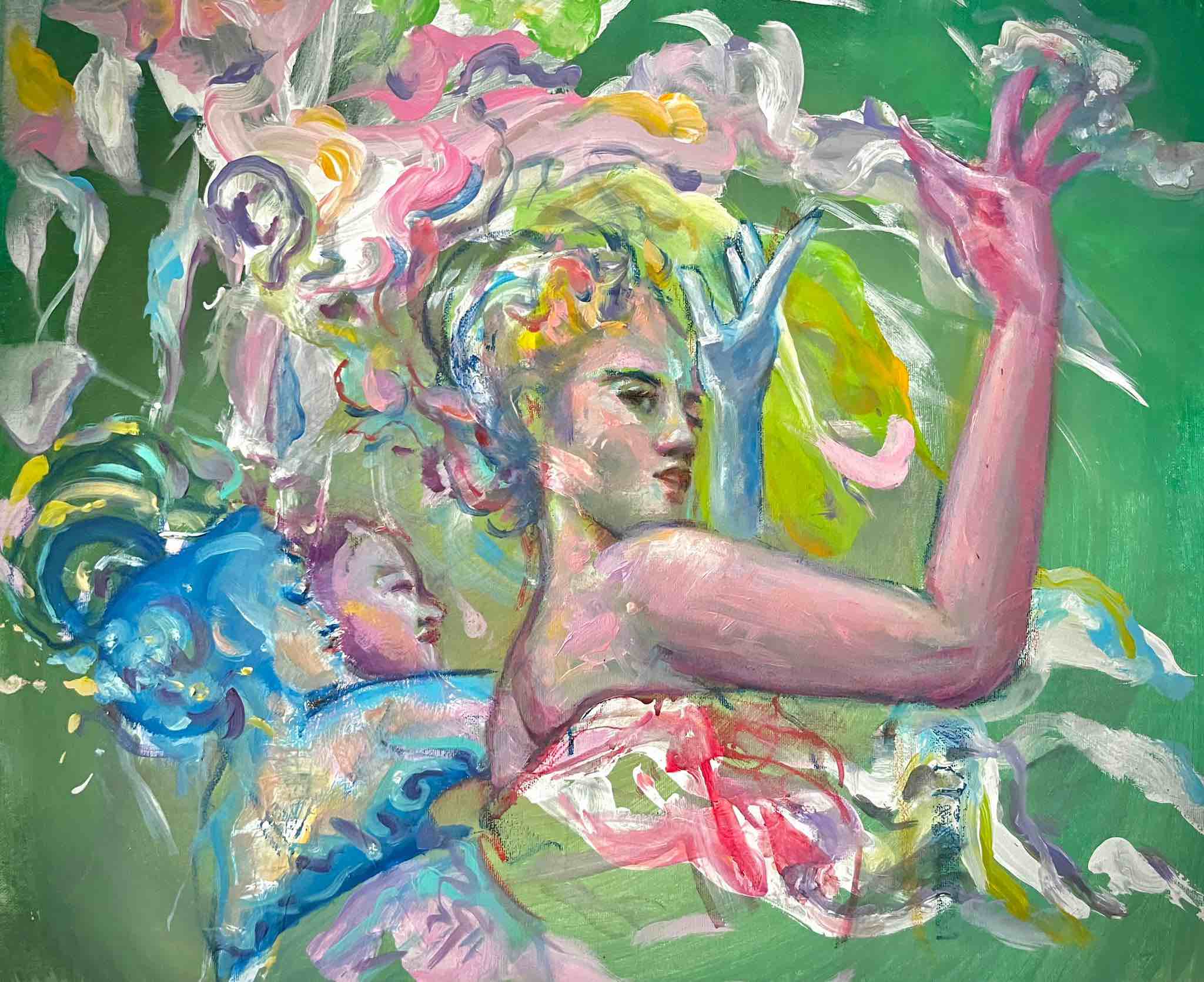

The art on display in his gallery is fresh, promising, and young, with affordable price points. It’s heartening to see a gallery that cares about artists and their messages, instead of just the dollar signs, but it is also clear that the pomp and ceremony which accompany work displayed in more traditional galleries are sorely missing here.

On a daily basis, there are no obviously auction-worthy pieces and anyone in search of the hyper-capitalistic excitement that follows stories of impressive sales like this one, by the likes of Liu Kang and Georgette Chen, may well be disappointed. However, Mr Lim’s Shop of Visual Treasures arguably offers up something far more precious—youthful energy, exciting new faces and a sense of hope in the future development of the local art scene.

In 2022, Lim organised a group art exhibition titled FOOLS featuring amongst others, the work of prominent artist Ai Wei Wei. While it was a success, he laments that all mainstream media wanted to know about was Ai Wei Wei, with very little critical review or conversation about the show as a whole.

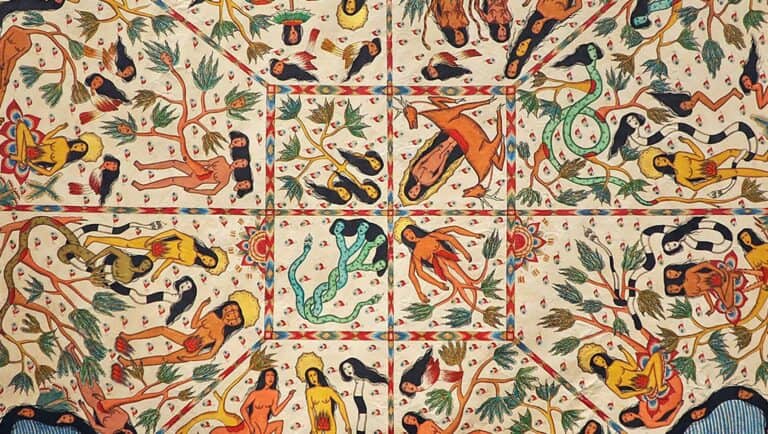

In the upcoming second edition of FOOLS which opens to the public on 21 July, Lim is once again anchoring the work of his younger slate of artists with presentations by local heavy hitters like Tang Da Wu, Goh Beng Kwan, Cheo Chai Hiang and (surprise, surprise) Liu Kang.

As Lim tells us, “One of Liu’s family [members] came by the shop and we had a nice long chat. He’s a great art lover, and really wants to contribute to helping young local artists, and promoting the art scene.”

He reveals that in keeping with the spirit of the FOOLS show, the work to be displayed is likely “a more playful and unusual piece.”

Why Liu?

“The man broke the mould,” Lim continues, “What was deemed foolish, to fuse the East and West and the Southeast, he did, and [it has now become part of] an important movement!”

How to make Singapore art great?

In the course of our conversation, Lim makes three interesting points about what he sees as difficulties in the local art scene. First, he critiques the heavy emphasis on grant application that accompanies any bid for government funding for the arts.

“Think of all these young kids who end up in art school because they are good at art but maybe come from broken families and a lot of trouble. [Maybe] they can’t do their O-Levels because they don’t have tuition teachers? They are good at art because they can draw, and they have some talent and aspirations. They do learn the rambling kind of thesis-writing in art school, but grant application needs you to be able to [at least] say what your practice is all about,” he says.

“If you write in broken English, the application will not go through. Edgier art doesn’t go through as well, so you end up with fairly bland stuff getting through. Selfie walls and murals, sculptures for the Minister to take a picture in front of, that kind of stuff,” he laughs.

“It is a very vicious downward cycle for these kids.”

His next bugbear is the issue of self-censorship.

“Artists, critics, nobody wants to say anything so we don’t grow. When we make things we are afraid of being POFMA’d or whatever. It’s horrible. We are afraid of grants, of [being reviewed by] panels [and of critics]…There is still a lot of fear about backlashes. If you criticise the wrong person’s art, then you may not get a gallery show or grants,” he continues.

Our conversation moves on to the state of art criticism in Singapore and we commiserate briefly on how it’s hard to unconstructively tear down a work of art that’s objectively not good—simply because anyone who has worked with artists will understand the amount of heart and soul that’s poured into the work.

Lim says, “Artists get so genuinely depressed and upset when their works don’t sell because it’s weeks of hard work and effort.”

And yet, he recognises the conundrum that we are such a small art community in Singapore, that “any chatter is good.”

“Whether it’s good or bad,” he continues, “as long as there is some, that’s good enough, it gets the ball rolling.”

Finally, Lim addresses Singapore’s focus on Southeast Asian art and wonders if such a framing offers too small a vision for the country’s broader artistic goals. For instance, he questions why we don’t have a “proper museum, like the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) filled with Warhols and Basquiats, when we can afford it.”

“We are as loaded as Hong Kong or Tokyo, and any first-tier city so why do we need to just be the ‘premium place for Southeast Asian art’?” he asks.

“I was making a speech at Chee Soon Juan’s restaurant the other day, with some other troublemakers,” he laughs, “and my point of view is that if you want innovation–real innovation–if you want us to create our own Apple or Facebook, then you need to support the arts. Every major city I have been to even in [places like] Estonia, they have a vibrant art scene to inspire the population. People may not end up becoming artists but they could become the next Mark Zuckerberg. If we don’t embrace new ideas as a country, we will eventually be overtaken. That’s my spiel to the non-art lovers—if you want to make money, if you want to have your own Apple then you have to embrace the arts.”

Noting full well the move towards decolonisation in the art world and the importance of acknowledging and embracing our home region, Lim clarifies that we should indeed have the best Southeast Asian museum in the world located in Singapore, if this is one of the country’s aspirations.

“But, he continues, “we should also have something like MOMA or K11 or even M+. It may sound materialistic but I think it’s important to make a statement that this is where our money is, and where we invest. We should show the world this, and we should show it to our kids. Our kids should get to see the best of the best—not just the best of Singapore and Southeast Asia but the best of the world, during their school trips and excursions.”

Find your own visual treasure

In a city where many high-end art galleries dominate the scene, and where art spaces can sometimes feel stuffy and exclusive, Mr. Lim’s Shop of Visual Treasures stands out as a refreshing and inclusive space.

Its location in Haji Lane also sets it apart—the area is buzzing with energy, filled with colourful street art, trendy cafes and unique boutique shops. It’s the perfect place to spend an afternoon exploring and discovering new artists. Mr Lim’s Shop of Visual Treasures fits right in with its cool and quirky vibe of Kampong Glam.

By prioritising the work of young and emerging artists, and keeping prices affordable, Lim is creating an environment in which art can be appreciated by all. It is heartening to see such a down-to-earth venture thrive in Singapore’s art scene, and we look forward to seeing what Lim and his artists will achieve next.

___________________________

FOOLS opens to the public on 21 July and runs till 6 August, prices for works range from $444 to $44,444. Click here to find out more about Mr. Lim’s Shop of Visual Treasures.

An earlier version of this article did not include a reference to artist Goh Beng Kwan, and included a generalisation referring to the National Arts Council which was not intended. We apologise for the error.