Chng Nai Wee does not cut a figure of your archetypal bohemian artist. When I spoke to him online, he had just finished a long day of work in his ophthalmology clinic. His passion for his eye practice quickly became evident: in noticing the picture of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies I had as my Zoom background, Chng commented how it was cataract surgery that preserved Monet’s deteriorating vision enough for him to continue painting.

But committing his time to both medicine and art only enriches Chng’s practices. His refusal to be categorised by a single professional identity reflects the fluid creativity and boundlessness of his art-making. These qualities were evident even when his artistic career was just in its nascency.

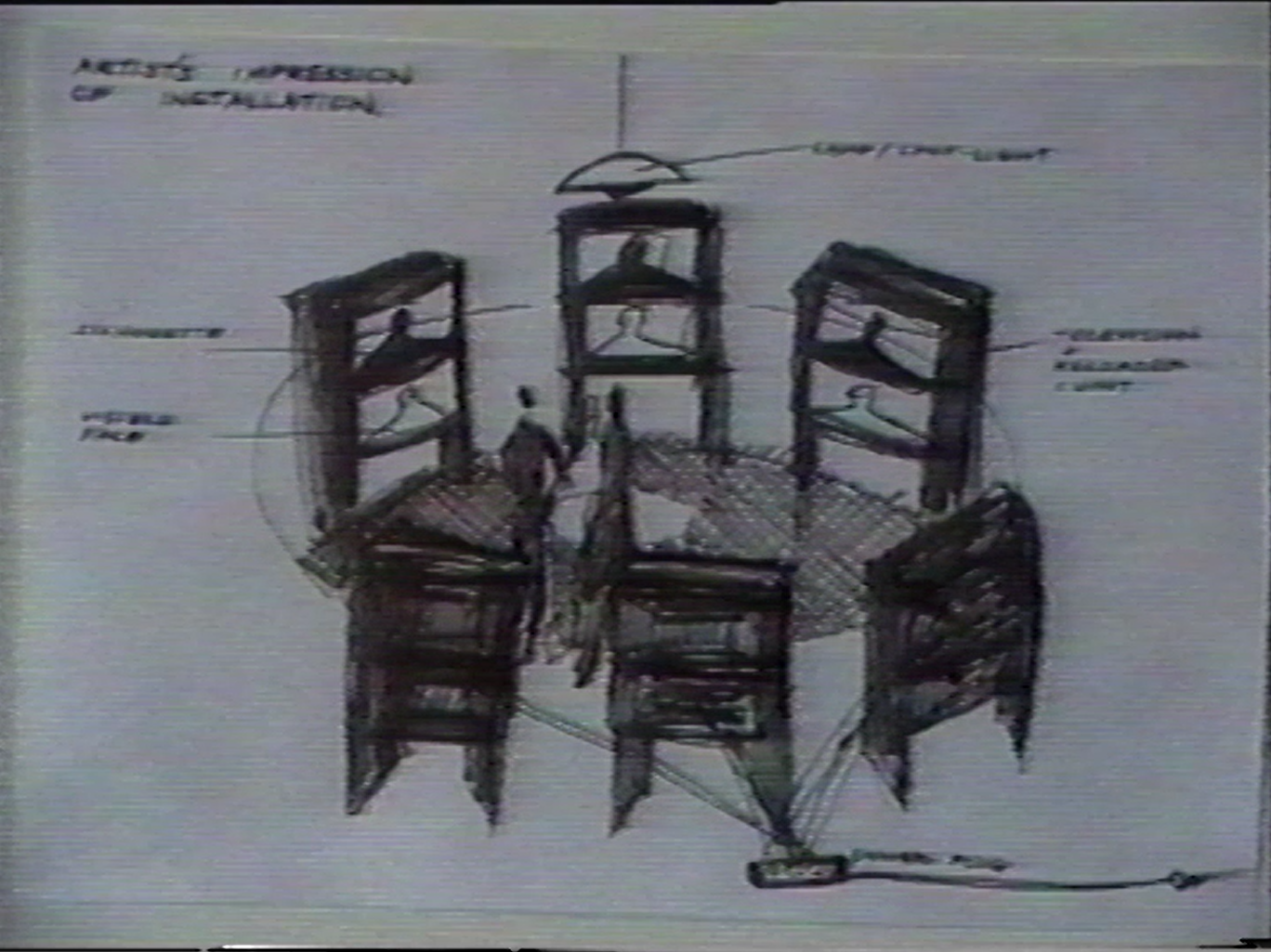

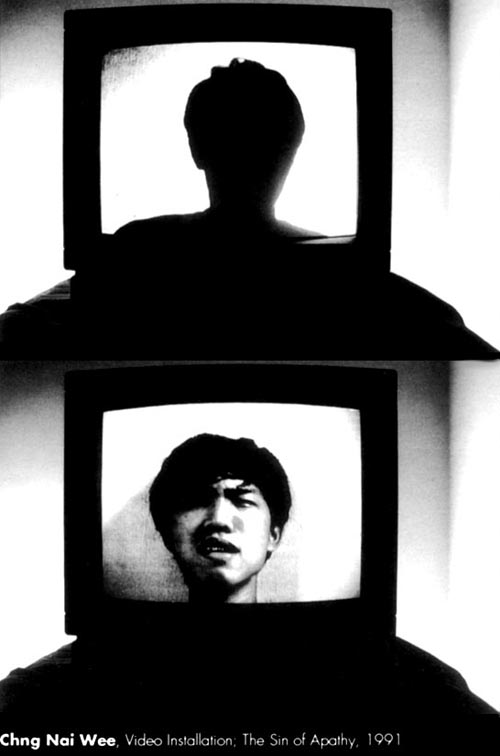

Indeed, over the course of this interview, Chng and I returned again and again to his groundbreaking experimental work Sin of Apathy (1991), now on display at National Gallery Singapore till 17 September 2023. Sin of Apathy’s presence in See Me, See You, an exhibition on early Southeast Asian video installation, is testament to Chng’s radical creativity and pioneering artistic vision. Using 12 cathode ray-tube televisions to encircle the viewer, Chng forces us to confront the diverse social crises—war, disease, famine, poverty, disaster, and refugee—personified by the actor on each screen. The work, displayed now for the first time since 1991, remains unwavering in its sharp-eyed examination of Singaporean society.

Read on for my conversation with Chng.

I want to begin with your dual identity of doctor and artist. How would you characterise the relationship between your medical and artistic practice?

Both disciplines require working within uncertainty. Though medicine involves facts, as doctors, we must apply our knowledge in interacting with patients. There, we work with inexact and incomplete information; there exist many ways to interpret what the patient tells you. I see this intervening exchange as a kind of artistic practice. Dealing with subjectivity requires creativity.

The same acceptance of uncertainty prevails in creating artworks. When an artist has a new idea, all there is to do is to try it out. That’s the best way of getting something done. But making art also requires systematic discipline in putting your ideas together. It is a measured process, in terms of breaking down the artistic process into specific combinations of your materials and techniques. That quantitative exactness is very much in the domain of science.

The two disciplines are not islands but two ends of a single continuum. In our society, art and science are separated into domains with clearly defined boundaries. In the past, even within each domain, individuals could only be an expert in a narrow field. If you were a sculptor, people expected you to understand a technique like metalwork and nothing else. But all these are arbitrary distinctions.

“As an artist, I redraw–or even erase–these boundaries to express the stories I want to tell. “

Previously, this breaking down of boundaries often triggered discomfort amongst people. But social mindsets are becoming more accepting of multidisciplinary practices. We have greater access to diverse ways of thinking and this freedom of access results in more interesting art.

How do you think this increasing access to knowledge and society’s changing mindset towards art and science impacts your work?

It impacts how I present my artworks because I need to think about how my audience will perceive the work. I am conscious of the cultural norms that influence the way the public understands art and the subject I represent in my art. This lets me frame my work in a way that conforms to or resists this dominant way of thinking, such that the artwork’s meaning is accentuated.

So, I take notice of the increasing accessibility of knowledge in our society. Before the internet, there were branches of information that you could only obtain through academic or professional specialisation.

For example, the only way you could look at a cadaver was to be a medical student; even then you had to request permission to go into the anatomy laboratory. Because of this, my past works that dealt with scientific or medical subject matter appeared unfamiliar to a general audience. I could present these artworks in a relatively straightforward way because their aesthetics were novel in and of themselves.

Nowadays, these works cannot carry the same amount of impact. Science and medicine are no longer esoteric subjects. Digital media and the internet have made it easy for us to look these things up and form impressions of diverse subjects. My past works must be considered in relation to the cultural context of their production. It is difficult for young people today to comprehend how much more inaccessible knowledge was. They might look at these works and wonder: I just saw an image like that on the internet. Why is it worthy of being portrayed in an artwork?

I was thinking about how this issue of changing contexts also applies to Sin of Apathy. Our relationship to technology has changed drastically since this video installation was first exhibited in the National Museum Art Gallery in 1991. How does this change affect the audience’s engagement with the work?

Of course, using cathode ray-tube televisions (CRTs) situates Sin of Apathy in a particular moment in time. It would be much easier to make this work now. The possibilities of its scale and its experiential potential would also be far greater.

Instead of 12 screens, I could have used a projector and had a hundred videos playing at the same time, in different immersive environments. We could have filmed all over the world, or used found footage of real events, or had live feeds. All these might have made for a more visceral aesthetic experience. In the past, production constraints made simplicity a necessity.

But as technology develops, the impact in art is lost. The new generation does not understand how difficult it was to use mediums like this. Back then, just carrying the television sets upstairs was challenging, let alone trying to record, edit, sync, and present 12 simultaneous multi-channel videos. It would have been easier for viewers to appreciate how these technological difficulties made Sin of Apathy’s production an impressive feat.

The work’s content, however, remains relevant. Perhaps the expectation was that technology should have helped to mitigate the social problems, such as poverty and the refugee crises, articulated by Sin of Apathy in 1991. But these issues still exist. In fact, that the work’s technology looks outdated or degraded speaks to how persistent the problems are across time, despite how far technology has progressed since then.

“Still, the quality of the subject of an artwork is the baseline for good art-making–technology cannot totally substitute the ability of an artist to compose a strong narrative.”

What else constitutes good art-making and how did you apply these principles into producing Sin of Apathy?

Artists must use sensitivity and imagination to bring elements together to affect viewers emotionally. Good art prompts viewers to connect their experiences to the big issues each work engages with, to see what resonates or what conflicts.

That’s why in Sin of Apathy, I wanted the viewer to be in the centre of the piece, with the gaze of the screens around them. It is them that the images in the work question, chastise, and appeal to. The work is only activated when the person is prompted to think and react to the images. This still applies even to individuals who despise the work or find it distressing, and therefore reject further engagement with it. They don’t want to think or accept responsibility for the social problems depicted.

Indeed, that is the essence of apathy. The decision to ignore any discomfort we feel with our inaction in the face of suffering and indeed, to remain passive.

How the audience responds to this realisation is the crux of the work. The work may even push people to finally confront their distress, to reject apathy. It’s interesting to see the variation in responses, especially if the reaction of a viewer has changed from when they first saw it in 1991. Those responses make the work.

The choice of subject and theme is important too. If the topic is trivial, you cannot create a meaningful story. When I made Sin of Apathy, I felt strongly that these universal crises also reflected how all individual actions are connected in the larger course of history. No one’s difficulties or successes exist in a vacuum. That’s what I wanted to interrogate.

Finally, nowadays, I think artists must look at how new technology can be incorporated into their works. After all, technology is what the spirit of today is activated by. I’m currently exploring using code to represent the human emotions that drive the market. To that end, I’ve been learning code as a way of expanding my repertoire of artistic skills. Conversely, I’m ready to turn away from skills like painting and pursue something that is more representative of the current age.

Was that the same sentiment you had in choosing video installation as the medium for Sin of Apathy in 1991?

Definitely.

What makes you interested in apathy?

There is already danger in inaction. Apathy, to me, is even worse because it is almost an active way of not caring about an issue. You decide not to react despite being aware the issue exists. I am interested in why individuals chose this pretence, as well as how apathy becomes an acceptable social norm when adopted by the majority. What is particularly fascinating is that this apathy of the majority is a silent conspiracy. It is an unspoken decision that everyone makes.

In Sin of Apathy, is the interest in a universal apathy or a particular social context in which apathy can be seen?

When I created the work in 1991, I was thinking about Singaporean apathy towards social issues in contrast to how our country was developing. Everything was valued on economic success and infrastructural development. We felt a lot of self-satisfaction as we felt that the nation had arrived on a global stage in those post-Independence years.

But Sin of Apathy aimed to question these rigid definitions, to introduce a new metric of success in terms of alleviating social suffering. I was responding to the fact that Singaporeans—even now—can have a rather simplistic and superficial view of social success. Beyond material wealth or educational attainments and connections, we rarely look at a person’s social contributions. Still, our society has progressed since 1991, be it by developing sports and arts scenes in Singapore and creating support systems for children with different needs. The social awareness today about these issues is more developed.

How do you see your future works responding to these developments in Singaporean society? Are there themes you’d want to return to?

There are social issues that I’d like to examine, such as land use and overcrowding. But I must engage with these ideas deliberately, rather than just make rebellious policy critiques of the current administration. As an artist, I want to find clever ways of presenting my works so that I can make constructive proposals and leverage the current social environment to express my ideas in interesting and subtle ways.

____________________________________

Sin of Apathy is currently on display at National Gallery Singapore. It is on display in the first half of the exhibition See Me, See You: Early Video Installation of Southeast Asia, which runs until 17 September 2023.

Click here to find out more about the exhibition.

Click here to find out more Chng’s artistic practice.

Feature image: Sin of Apathy in 2023, restaged for the first time since 1991, at National Gallery Singapore. Image Source: National Gallery Singapore.